Interview by Dorothy Berry

Dorothy Berry: On themes around the archive and filmmaking, you’ve talked about the lack of Jim Crow edifice in Hollywood films—something we sort of called “contemporaneous historical revision.” Could you describe what you were seeing or rather not seeing in those films?

Christopher Harris: During the Jim Crow era, white supremacy was thoroughly integrated into every institution including popular culture. Racist caricatures were manufactured, sold, displayed, and used in homes all over America, most often in the form of salt and pepper shakers and kitchen utensils—objects associated with the domestic sphere. More to the point, lynching was widely celebrated and not just by clandestine, hooded night riders like in the movies. White men, women, and children gathered for the lynching in broad daylight and posed for pictures with their victims. They smiled, laughed, and celebrated during these festive events. They tortured their victims, who were black men, black women, and black children. They hung and burned them, and cut off body parts (genitals and toes) for souvenirs, and sold postcards documenting the lynched bodies.

This was ordinary and accepted by the white working class and white elites so I find the absence of blatant racism in cinema of the Jim Crow period completely and utterly baffling. How is it that in the cinema of the day, evidence of white supremacy is erased from the record? What I mean by contemporaneous revisionism is: what was otherwise pervasive and normalized in daily life was effaced in cinema. It’s as if there was an understanding that indeed, virulent, white supremacy was not something to document or celebrate with unabashed pride without exposing a trace of self-consciousness, shame, or guilt, as in the festive lynching photos of smiling white women and frolicking children. This can’t be explained away necessarily with Cold War politics and the need for propaganda since, of course, the cinema of the Jim Crow era pre-dates the Cold War before overlapping with it.

In the film Pearl Harbor (2001) with Ben Affleck, there’s a long sequence at the beginning of the film set in the officer’s club, followed by a bombing scene… there’s this whole jingoistic kind of thing. But wouldn’t it be nice to see an enlisted Black man attempt to enter the club and be turned away during the film? The protagonist or “hero” we’re supposed to identify with and root for is portrayed as someone who loves his children, who is kind to his dog, and does charity work, but oh, he also hates Black people… those edges are smoothed over.

Harris: Right. The same law just as easily leads to mass incarceration of black and brown people, which Finch would accept as legally sound. I’ve read that the little southern town on the set of To Kill a Mockingbird was reconstructed from houses that were demolished to make room for Dodgers Stadium in Southern California. Basically, the production of this film about the rule of law, tolerance, and so forth benefitted from the displacement of mostly Latino and poor communities. That’s deeply embedded in the way this country represents itself to itself.

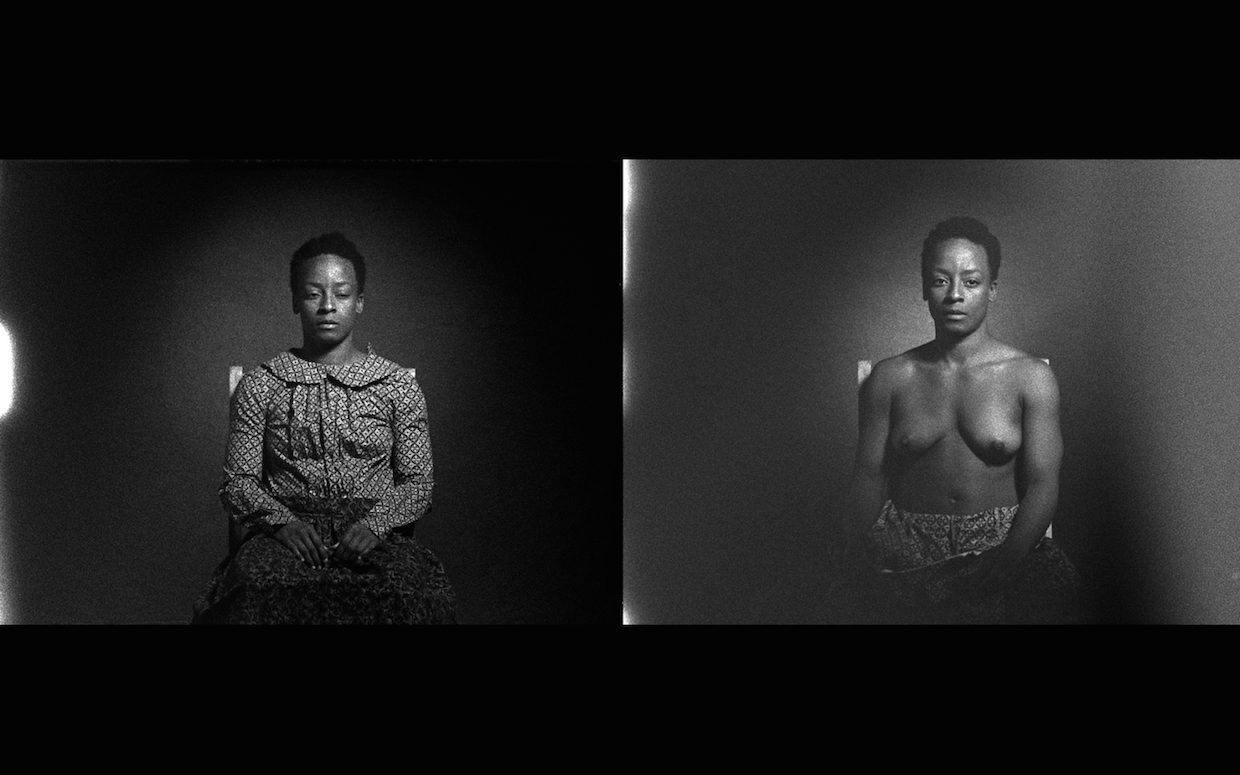

Berry: That leads me to a film you made that gives background to slave daguerreotypes. I believe it was originally a part of an installation?

Harris: It was a two-part video installation. The first part is titled A Willing Suspension of Disbelief (2014), the second part is titled Photography and Fetish. It’s a creative reimagination of the interior life of a woman who was photographed for slave daguerreotypes. What made you think of that?

Berry: It made me think of what we don’t see… that sort of historical process. There so many famous slave daguerreotypes and I think about that often reprinted photograph of an older African American man whose back is completely scarred up [The photo is of a man identified as Gordon or Whipped Pete.] Anyone who’s spent time thinking about Black history can picture that exact man…

Harris: Isn’t that the famous photo from The Black Book (1974)? I always associate it with that.

Berry: I associate it with a different book that my father had! It’s everywhere. It makes me think: What was the situation there, really? Why was a semi-nude photograph taken of this older man’s scarred-up back?

Harris: We don’t have that history, do we? Is the image unmoored from context?

Berry: I think the context exists, but the received context in a lot of cases is as simple as “such and such took photos of enslaved people…” I’ve received it as something generally abolitionist oriented in support of Black liberation, but did the person photographed know that was the intent? Was he an activist? What’s his involvement? Did he say, “I have the evidence on my back?”

Harris: Again, this goes back to earlier questions. Maybe the person who took the photograph was glorifying slavery, like in lynching photographs.

Berry: Can you explain this idea of erasing the past, or creating the past through one of your films, my favorite of your films, Halimuhfack (2016)?

Harris: Halimuhfack is composed of a performer lip-syncing to archival audio of an interview with Zora Neale Hurston from the 1930s. She describes her anthropological method in gathering African American folkways and folk songs throughout the south. The title of the film comes from one of the songs, “Halimuhfack.” Behind the performer, there is a rear projected 16mm film loop from an educational film about Maasai tribesmen and women. The film and audio break down into a loop while the rear projected image breaks down into an abstracted superimposition that speeds up, plays backwards, and deconstructs.

Berry: What inspired you to combine those two geographically and, maybe, chronologically disparate images?

Harris: I was thinking about syncretism, cultural retention, cultural memory, and Africanism present in African American culture. It’s kind of a liminal thing—it’s about being aligned and not aligned at the same time. In the actual text of the interview, Zora Neale Hurston speaks on how she learned African American folk songs from people and carried it wherever she went, bringing to mind the Middle Passage and how Africans weren’t able to bring their material culture with them but brought other cultural forms: music, dance, language, and oratory. I would also say to some extent agriculture and cooking, because that’s what they were there for, to plant and to feed, right?

Berry: None of us would be here if they hadn’t brought rice cultivation here, too…

Harris: Right, exactly. In the holds of the ships they still brought some material culture over. For example, African forms in southern architecture, in certain buildings of the Black Belt.

Berry: Going back to “erasure,” this idea of forgetting of the past, we say: “They brought this agriculture, and it’s crazy that they brought it over,” but if you read, not antebellum, not 19th-century, but 1600s, 1700s slave advertising, they specifically marketed rice cultivation, they marketed specific regions and people were brought over from specific regions that were known for rice cultivation.

Harris: Right! And other skills as well! There were specific regions that had traits associated with them, whether accurate or not… some of it was mythology.

Berry: The idea that we were brought over with nothing but survived is an idea that people take positively. But in reality, that plays into the idea that there existed a group of Black people who were completely blank slates.

Harris: Oh yeah, but we brought over a lot! It’s fascinating that on slave ships and plantations, you have this admixture of Africans—first, second, and third generation slaves from different countries and tribes setting the precedent of what African Americans are today. Whatever that admixture is, that’s what we are and, obviously, being in the midst of European culture, it’s like this weird thing, but you know, I don’t know how white people view who they are, you know?

Berry: It’s interesting, always, because you hear white people saying “I’m just a European mutt! I’m Irish and Scottish and French and German.”

Harris: But what does that mean? It’s more than the genetics, right?

Berry: Sometimes they mean it to say “That’s why my family celebrates Santa Lucia Day in the middle of December, but also we do the Italian Feast of Fish on Christmas Eve,” which is describing two distinct cultures. What they’re really saying is that they didn’t retain a lot about their family history.

So bringing the idea of history in filmmaking, I want to talk about still/here (2001), which over a long period of time covers the architectural degradation that exists in St. Louis, Missouri, where you’re…?

Harris: Yes, that’s where I’m from. The neighborhoods you see in the film is where I was born and raised.

Berry: St. Louis is an interesting city, architecturally, because it was the hub of the bricklayers union, the national brick masons union, so it has beautiful brick buildings throughout. It’s one of the few places I’ve ever been to, or lived where the buildings that are boarded up are often architecturally stunning.

Harris: Those are the places, the streets, that you see in a film like Meet Me in St. Louis (1944). Bourgeois, upper crust white families lived in these homes that are now abandoned. But you know there’s a history of the north side of St. Louis that is still to this day African American.

Berry: I was just in St. Louis in November, near U-City, and I was walking through a neighborhood I’d never walked down before, and based on the decorations people had up, it was clearly an African American street—there were a lot of plastic Black angels. A brick house in St. Louis is a mansion, comparatively with other places, and so the film kind of brings you into this fantasy of a city full of fancy 19th-century buildings that are the “garbage” buildings of the city. People aren’t going in and saying “oh wow, I have to buy this one,” they’re getting boarded up, torn down so people can build…

Harris: Well, you know, St. Louis was in competition with Chicago for a long time as the main center of the Midwest. It’s an artifact from an era when St. Louis was this major bustling city that was equal to Chicago, except Chicago kept expanding and St. Louis couldn’t keep up.

Berry: What inspired you to go into the city and make this kind of really long-form, marathon film? To watch it, you have to commit to that film.

Harris: It’s part of my aesthetic and it’s almost a question of ethics. You’ve got these ruins that are an impression of the past in a present moment. When you enter a ruin, you’re entering a space from the past, which is the genesis of the title of the film still/here. There’s something infinite or eternal about the expanse of the ruin, it’s a timeless experience. So time had to be a structuring element of the film, duration had to be a structuring element of the film. The experience of ruins as temporal and spatial displacements had to be felt through the duration of the images, and that motivated the choice to use this long -form, extreme duration.

I was also inspired by African American musicians, particularly people like Miles Davis and Roscoe Mitchell. They were very important to the making of this film. I was thinking about how Miles would hold a single note for a long time. He would structure the solo around gaps and silences, so in order to use duration in this way I would have to have stock static shots, places where the sound would drop out. For me, the long duration of the static shot was the filmmaking formal or equivalent to the gap in the space where not much happened, where there wasn’t a lot of movement within a frame, or where the frame wasn’t moving much. I wanted to be able to experience time within the film and that’s why it’s a question of ethics because the viewer has to give their own time in order to watch this film. It’s not a film that you can fast forward through. I wanted watching the film to be a kind of embodied experience of these places, in the fact that you’re feeling duration in your own body at the moment of viewing, of spectatorship.

still/here, 2001