Interviewed by Jonathan Bruce Williams

Liz Deschenes: Look at you with all your texts.

Jonathan Bruce Williams: Well, that’s Judd’s “Specific Objects,” which is really about a specific time and place.

Deschenes: What class are you reading that for?

Williams: I wasn’t. I guess I thought it was relevant for thinking about your installation [Liz Deschenes: Gallery 7] at the Walker Art Center.

Deschenes: Totally. Judd obviously comes up a lot. I just read Anna Chave’s piece [“Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power”] with my undergraduates, and I guess don’t think of my work as being as fixed as he imagined. Not only his work, but other artists’ work. The permanent display—that’s not a huge interest of mine. The hand versus the machine is something that I’ve investigated in a way that wasn’t of interest to him at all. The photograms are so handmade that the hand, as you can see, is still in them.

Williams: Right, they’re very organic and chemical in a certain way. And the mechanical reproductive part of photography is really stripped out of them.

Deschenes: There’s no machine in those procedures. Everything about it, from the trays that a friend of mine made for me to me making them, is about the lack of machines. I’ve taken the camera out. I’ve taken the enlarger out. I’ve taken all the machines out. I’m not saying there’s not a machine that made the paper, and obviously there’s a machine that mounts the work. But I’ve stripped it down of mechanisms as much as you possibly can. Obviously Judd’s sculptures were very industrially produced. I actually think an artist to look at in relationship to Judd, who makes a lot more sense than me, but to very different ends, is somebody I’ve exhibited with, Charlotte Posenenske. She stopped making work in the late-’60s. All of her reliefs were available in open-ended editions, and they still are.

Williams: So they’re eternally reproducible.

Deschenes: Yes. I like that— eternally reproducible. You can order them in certain sets. There are certain limits on what you can order in terms of shapes and relationships, but in terms of them having the possibility of being manufactured, that’s completely open.

Williams: That her sculptures appear as duct work seems to me to be related to this reproducibility. It’s an industrial service—heating, ventilation, and air conditioning—and ducts are industrial objects that are highly repeatable. In this studio, in this space we’re sitting in, I have this type of ventilation system in here. It was modeled and created in a 3D print as a part of a sculpture. Digital technologies and production like 3D printing is related to the machines that you strip out of photography. So I guess I’m wondering, so much of our industrial production and our market is driven by a manic reproducibility of objects for commerce and sales. Maybe I’m extrapolating or overreading, but do you have an aversion to that kind of mechanical reproducibility?

Deschenes: No, because alongside objects defined by their singularity, I also exhibit state of the art inkjet prints, and I could make a bazillion of those inkjet prints. So no, I don’t have an aversion to mechanical reproducibility. I like taking seemingly opposing things and positioning them together.

Williams: I’m also considering my attraction to analog cameras and materials from the past. I’ve sort of moved away from that now, to digital time-lapse, because there are an unlimited number of pictures that can be made with it, and all this digitally fabricated stuff is very of the moment. When I was an analog 4×5 photographer, everyone pinned me as a Luddite. Everyone suggested, “Oh you’re nostalgic for this earlier era, and you’re afraid of progress, and you’re moving backwards…”

Deschenes: Can’t you move backwards and forwards at the same time?

Williams: Right, or be in the present. I think that in terms of my engagement with these materials, I was dealing with a kind of wreckage of modernism and the ubiquitous movement of consumer analog photography, and how it generated this rubble after it had been superseded.

Deschenes: What were you photographing with the 4 x 5 camera?

Williams: I would build sets and photograph the sets, and that’s how I ended up coming to sculpture. I just got more interested in building the sets. But the photography sort of inferred itself in other ways, especially with the use of light.

Deschenes: And now you actually have a living organism in it. I think that’s a really nice way to talk about your interest in photography. What kind of plants are in there?

Williams: Broccoli and Kale. I set it up as a system, from seeds, and it just took off. I was thinking of it as a Dan Flavin hydroponic system, because there’s a funny Minimalist history to this appearance.

Deschenes: I think, like you with your hydroponic Dan Flavin, I’m also obviously playing with the tenets of Minimalism. But the work’s going to change.

Williams: Your work’s going to change?

Deschenes: Sure. I haven’t been back to Minneapolis, but I presume there’s some oxidization happening. I would presume that on a daily basis there’s an experience that people are having with the work that’s not recorded. It’s like an accumulation. It’s interesting that we’re sitting here talking about the never-ending shutter going off incrementally [in your studio]. That obviously happens with the work in Gallery 7 as well, only with no record of it. How many files do you now have going on over there?

Williams: They usually run, for one set, four days, and it’s like 5000 or 6000 for every set, one image is captured per minute. It’s really too many images; it’s very difficult to deal with. But it’s like movie film—it’s toward the production of one image.

Deschenes: I’m interested in that continuum, without having either a file of it or a negative of it; I’m interested in the continuum but I don’t feel the need to control it or possess it or databank it. But the same thing’s happening out there [at the Walker] without me having any sense of who’s visiting, or when they’re visiting. So I think in relationship to some of the things we’re talking about, I set up a series of decisions, and then those decisions either get enacted upon by the viewer, or they don’t.

Williams: I guess that’s part of the work, that either the viewer engages with it or won’t, either reads it the way you wrote it or won’t. We spoke earlier [in a previous exchange] about mirrors and windows, which I know you’ve dealt with extensively. John Szarkowski used these terms as metaphors, which I suspect you’re less interested in, but he also describes them as a kind of spectrum, a continuous axis that isn’t like a binary, that isn’t one or the other. So in approaching the mirror and the window not as a dichotomy, I think about a beam splitter, or a 50-50 glass. It’s like the scopic spectrum of introspection and extroversion, not a gradient but a focal relationship.

Deschenes: That’s really nice, the focal relationship, because as you know, with the focal relationship light is always becoming reversed, so that up becomes down, left becomes right. So to think about all of these things optically makes a lot of sense.

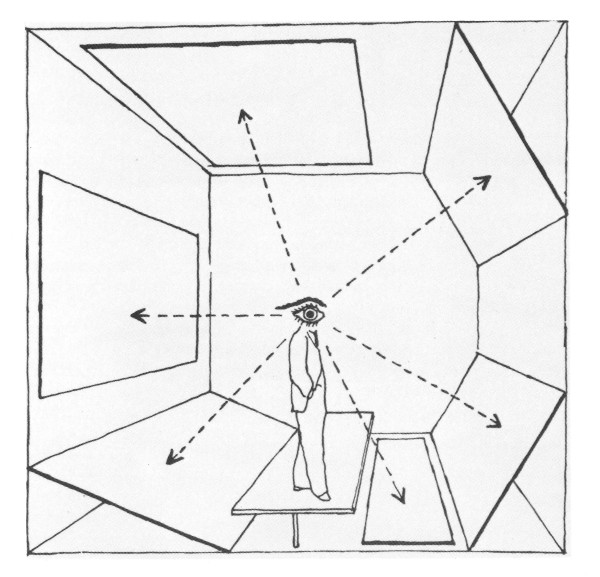

Williams: And also what is out becomes in, with a camera, or in the space of Gallery 7 at the Walker. The extroversion becomes the introversion, and then in projection, the introversion becomes an extroversion. So instead of thinking of Gallery 7 as a gradient, I think of it as being focal, there’s outside and inside, but then, of course, there’s the optical focal point and to me that’s like the 50-50 split, like the moment of the beam splitter. And so it’s like mirrors and windows. I mean I’m sort of extrapolating from that idea and the way I place your practice, from my understanding of it, into that metaphor, but it really functions more like a beam splitter, like a classic front screen projection beam splitter. I was thinking about that arrangement in diagram, and also of Herbert Bayer’s Diagram of 360 Field of Vision that you have worked from, as a metaphor for the artist/viewer relationship, where you would be like a projector—you have research and information and those are like slides, and you project them into the 50-50 beam splitter, and then the viewer would be like the camera, the observer, the person looking at the installation. And the projection screen is like the gallery itself. It’s about aligning something coming out from you, as an artist, and something being apprehended, as with a camera, by the viewer.

Deschenes: That’s really nice. I actually referred, in Tilt/Swing (2009), to precisely what you’ve said. Obviously, the work is referring to camera movements with its title, but the viewer has the capacity to become the liberated camera, hopefully. There are numerous vantage points that the camera only can begin to aspire to in terms of positions, because the camera’s vantage points are fixed or limited, whereas the viewer has the capacity to act like a camera but with even more fluidity and even more options.

Williams: And with more perspectives.

Deschenes: Yes, and I love that drawing, that diagram.

Williams: The application of the front screen projection technique that I think of the most, I mean the most famous one, is from 2001: A Space Odyssey—the scene in the beginning with the apes, the men in monkey suits jumping around in front of projections of 8 × 10 transparencies onto reflective material. It’s a compositing technique, which I know you’ve also made work about before: the blue screen process. I’m interested in how you’re working with this kind of lineage or genealogy of photographic and media production techniques.

Deschenes: I think once again it’s about revealing what is hidden. When I’ve made subject matter, be it the blue screen or the green screen or the moiré pattern, it’s what gets removed in the process, or eradicated because moiré patterns are an artifact that is not desired. In looking at these processes or procedures, I also want to look at what gets taken away as a not desirable result.

Williams: Right, like dust on a negative.

Deschenes: I like the dust on a negative. I also want to say that I like the drawings that you have because a lot of the work comes from drawings that never got brought to fruition. And as you can see with the diagram, too, the Herbert Bayer one changed a lot in terms of giving the viewer more space and more possibilities than what he had proposed. And there’s a viewing platform…

Williams: Yeah, the funniest thing about that diagram is that the whole head is an eye.

Deschenes: One eye.

Williams: One monocular eye, which is really kind of telling. I wanted to go back to get at something about front screen projection and what you were just saying about the moments when things break down and we try so hard to remove these distracting elements. When it’s the alignment, thinking again about this metaphor, of the artist as projector and the camera as viewer, when they’re misaligned, when those optical axes are misaligned, you see the shadow of the projection. That’s the distraction of the misinterpretation of what is being projected. It’s a distractive force. Maybe that’s a sign of misperception? I was wondering about the moments in your work in installation when you’ve been aware of a misperception.

Deschenes: I think the work is about perceptions, but not about experiences, because I don’t want to dictate experiences with the work. It’s not about deciding what’s perceivable or not perceivable. It’s much more about looking at some of the conditions around it. It either has a version of working with cameras—it obviously does that—or it has a sense of reductiveness. But the mis for me is the misreading of the materials that are used in the work and not the actual experience of the work. People misread the materials all the time, which is in part why I showed, in Minneapolis, both the front and the back of the work, which is another photo reference—you have recto/ verso, and I’ve reversed recto/verso in Gallery 7, so you see the substrate, the backside first, or at least with the photogram work. I wanted to point out the material conditions of the work, that this is metal, and this is paper. This goes back to what I listened to last week at MoMA, with Kaja Silverman talking about recto/verso and placing the viewer in relation to recto/verso, how they are somehow implicated in the recto/verso, that it doesn’t just stay there, that one’s reading of an image continues to evolve over time, that it’s not situated just in that particular moment. So to go back to Judd again, I’m more interested in the continuum, in what you reference as the spectrum, than I am in the specific. Because I’m not interested in specifics, I don’t think there really could be a missed opportunity or a misinterpretation.

Williams: That’s very interesting. But you do a lot of research.

Deschenes: I do obviously do research, and a big part of the project that was of interest to me in that particular gallery was looking at some of its histories and allowing it to have a relationship to looking out on the landscape that is generally prohibited by neutral density. So yes, I do research, but that doesn’t mean that I think somebody should have a particular experience. I don’t know if you saw the reaction from a particular reviewer?

Williams: Oh yeah, I definitely wanted to talk about this. It’s funny to me because Mary Abbe is perhaps the only art reviewer in town—it seems that she is the only person who is a salaried art reviewer in Minneapolis.

Deschenes: One? Wow.

Williams: She’s the one person in town who will write the review, and she has been doing it for decades.

Deschenes: She actually did exactly what I want viewers to do.

Williams: I thought it was interesting because she really bashes what you did, and then she lays out all this history.

Deschenes: Which is exactly what I wanted.

Williams: I know. She was like, this is a terrible show, and then…

Deschenes: It was probably the most dismissive review…

Williams: Incredibly dismissive. And then she writes everything you were trying to make the show about.

Deschenes: And that was everything I was trying to do. I really wanted people to think about the history of that space. And for her, she preferred other incarnations of that space. I think that in terms of interpretation, those were my highest aspirations. So the most dismissive review resulted in… well, that space has had many lives and incarnations that have been, I don’t know, they haven’t been white-washed, they’ve just become part of the space. I like that you got out the Projected Images [Walker Art Center, 1974] catalog.

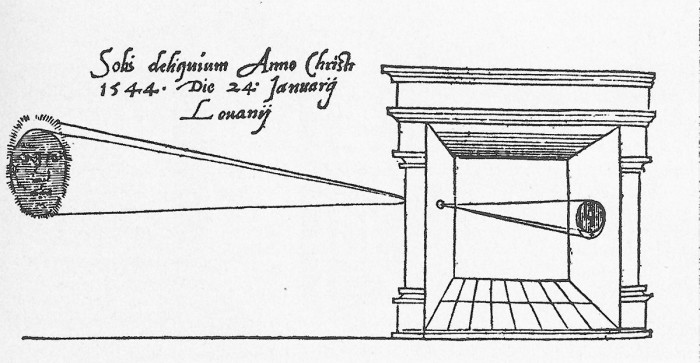

Williams: Yeah, it’s kind of what started this conversation. The Rockne Krebs installation from the Projected Images show was literally a camera obscura installation. This is one of the nicest printed versions that I’ve seen of this classic diagram by Gemma Frisius. This diagram, as a historical artifact, has always indicated to me the natural state—that photography is a force of nature, that it is cosmic. You’re making these photograms of the night sky illuminated by the moon, which is reflected sunlight. In some ways, it’s like the moon is the mirror, the reflex action of the universe. An eclipse is like a shutter, a solar eclipse is like a momentary lapse of light, and then the rest of the time is like an exposure. It’s in this diagram that so much of your installation is encoded. I think it’s really interesting, it’s place in history. And also that there’s a logic to photography that’s a logic of nature. This is visible in a camera, like a Bolex, which is the other thing I have out…

Deschenes: I saw your Bolex.

Williams: Which, because it combines these two things that I wanted to mention—it’s a reflex by way of a beam-splitter, so light comes through the lens and then bounces into two places, between two prisms, one to the eye and one to the film, and it’s also…

Deschenes: What shape is the prism in your Bolex?

Williams: It’s rectangular. This is it right here. It’s an incredibly fragile piece of the camera. But you can sort of see the place where they intersect. The shutter in the camera is called a half-moon shutter.

Deschenes: I didn’t know that. That’s nice.

Williams: Yeah, and it looks like, what would you say, a waning or waxing moon. It’s a crescent. And maybe it’s an extrapolation, but it’s named after a natural form. There’s this connection, through photography, to the cosmos.

Deschenes: And you have no idea if that moon is waxing or waning.

Williams: It could be doing both at the same time.

Deschenes: That’s really nice. What are you shooting with a Bolex?

Williams: I guess I started as an undergrad studying film. I haven’t shot anything recently. I shot something last summer, though to me it’s a home movie. But I haven’t made a project that used 16 since 2012. I’m really more interested in its engineering than in using it as a tool. I have four of them. They were a dying technology so they were going in the dumpster. At MCAD, where I was an undergrad, they were getting rid of all of them, for like $150. I got three, with lenses, and now the lenses are each worth like $250. It’s this technological story of things being ubiquitous and then scarce again.

Deschenes: And then they get folded back in. So the lenses are actually somewhat valuable now?

Williams: Yeah, eBay valuable, if you get someone to buy it. You were talking about how you strip the mechanisms out, but maybe I’m thinking about…

Deschenes: But maybe I’m putting them back in, too, I don’t know.

Williams: I think you are, also. Because they’re not mirrors, but the mirror-like quality and the shape of them is like this keystone. That’s a perceptual effect. But in an SLR there is a mirror, an actual mirror showing you an image and showing it to something else, and showing it to you again.

Deschenes: I guess I’m more interested in the actual than I am in the metaphor. My work is keystoning in those frames. It’s not a metaphor for a keystone, it actually is. And I really like that drawing that you sent me—I feel like you sent me a drawing, or maybe I looked up a drawing—when you asked me about the keystone. I like how that would hold other pieces in place. The idea of place, and these things being placeholders, I’m certainly interested in, and I’m also interested in the ridiculousness that these photographs could not only hold place but that they could determine how you maneuver space. Because people don’t think of photography as being architectural, and the keystone is truly an architectural reference. It has a real function. And I’m interested in these photographs functioning in a way that delineates space and doesn’t allow people to access space. So once again, there’s a removal. People expect to find photography on the wall. You don’t find photography on the wall, you actually find it in the place where viewers generally navigate. So I’ve displaced the viewer with the photographic works, so they have to find other ways to move around the work. You can’t move through the work because I haven’t left enough space for people to move through the work. You actually physically have to move around it. So I guess you’re right, I have stripped things down, but then I’ve replaced them with things you don’t expect to find. You don’t expect to find freestanding photographs on the floor that don’t allow you to maneuver space. So I guess there is a bigger demand on the viewer than I’ve made previously. Because with Tilt/Swing people were allowed to walk, at least in its first incarnation people were allowed to walk in it, through it, around it…

Williams: It was more immersive. More of an environment.

Deschenes: It was. And I think that Gallery 7 sets up a more difficult proposition.

Williams: I wanted to ask you about the difference between Gallery 7 and Tilt/Swing because in Tilt/Swing there are still parts of the work that are on the wall. It’s as if they’re moving up or moving down off of the wall; it spatializes this in-between moment. There are other works in which you have one of your photograms framed and it’s much more of an image-object than it is an installation. And in Gallery 7, they’re objects. They’re maybe sculptures. I’m not sure I’d place them in sculpture, but they’re architectural—they’re on their way to architecture, and maybe it’s that they just happened to momentarily pass through sculpture.

Deschenes: I like that because it also refers to the keystone, which is part of a threshold.

Williams: For sure.

Deschenes: So the passing through, the momentary. Those are helpful ways for me to think about the work.

Williams: And their ability to stand—that architectural, objective quality—made me think of them as monoliths. They have this monolithic quality, like an outdoor structure maybe.

Deschenes: That’s interesting because what you don’t see in the work, what actually is hidden, is that there are weights on the bottom, so that it doesn’t topple over.

Williams: A counterweight. It’s an engineering problem you’d find in architecture, like a cantilever. But I think of a monolith like Stonehenge, which is maybe a bad example. It’s well known but it’s also enigmatic; maybe they don’t know exactly how it was used or what it is, but they know it was something celestial, something that had an interaction with the sun and the stars. A sundial, perhaps.

Deschenes: Have you visited?

Williams: No, have you?

Deschenes: No, but I’d really like to. I think I may have already talked to you about some of the things along these lines that have been of interest to me. I’ve visited the Greenwich meridian and I want to say that the Greenwich meridian has a beam splitter on site. I mean standardized time arrived when there had to be a cohesion of schedules. Paris had standardized time before it got relocated to Greenwich, and what the French gave up in losing the marker of standardized time was that the British were supposed to adopt the metric system. Part of understanding demarcations was that the metric system was the measurement used to figure out longitude. There were many meters and there was one established meter that I want to say François Arago was responsible for. François Arago is also responsible for presenting Daguerre’s daguerreotype. So all these systems of measurement are linked.

Williams: Regarding measurement and the idea of the installation of Gallery 7 being up for a year, I was thinking that it’s like a measuring device that doesn’t give an output. A metric is a system, but the unit itself and what it’s derived from is potentially arbitrary.

Deschenes: Oh absolutely. There was more than one meter…

Williams: And that it’s really just the base 10 organization. That’s the system. Somewhere there is the singular qualifying gram, but it’s atomically losing weight. It’s decaying.

Deschenes: Oh that’s funny. I want to say that across from the Luxembourg Garden, outside the French Congress, there is the metering system that was evolved—the one meter. So I mean those are some of the things that I’m interested in. That’s in the large form. And then in the small form, which I’ve discussed, is the proportion of the index cards that Lucy Lippard used for her Numbers exhibitions. So if the metric is one of the historical references for Gallery 7, which corresponds with the measurement of light and time and space, then Lucy Lippard’s very basic index cards as a way of cataloging her artists’ participation in her Numbers exhibitions is the other physical referent. So I used the proportions of those index cards. The Walker Art Center was one of the venues for her c. 7500 exhibition that, if I have the story right, she asked Martin Friedman for help on, to produce the catalogue, and he not only responded with help with that but also with the physical space, which was called Gallery 7 at that particular time. I think it was 1973.

Williams: That’s a very specific piece of information that’s in the installation. But it’s only when you read the invitation to the exhibition that this information is conveyed. I need that information to read specifically into the installation; it’s something I need to know to understand how the work is framing itself. That’s the history. And so I guess this is a required document? And it’s also an incredibly aesthetically charming one.

Deschenes: Dante Carlos is an exceptional designer. And that’s probably something you would have found in the Lippard exhibition as well, a similar takeaway as opposed to a wall text. Every image I’ve ever seen of those exhibitions—I don’t remember ever seeing a wall text. There’s obviously no wall text in my exhibition, but there is this takeaway. I’m glad you took it away. And that’s obviously the other reference, the museological one of the blue, which comes from the textiles used to measure how much any pigments change over time, the indigo being one of eight colors. In my next project I’m actually going to look at the recto and verso with these eight colors played out, for another exhibition that will be on display for a year. I’m doing two shows at MASS MoCA. One’s an invitational, with the premise that I’m not a curator, so the artists I’ve invited have a better understanding of what’s pertinent and urgent in their own work right now, in one gallery, and then in another gallery I’ll have five pieces that will all be double-sided, but all in resin with a pigment print in them. There will be no reflective surfaces.

Williams: Oh wow, a digression. I love that you have two year-long exhibitions overlapping.

Deschenes: Yes, the second opens May 23rd, and you have a whole year to get there to see it. I love that you have Matt Witovsky’s article [“Another History: On Photography and Abstraction”].

Williams: Actually Jonathan Thomas lent it to me. I remember reading it the first time, and it really stuck with me.

Deschenes: I like the way Matt frames the history of abstraction through practitioners as diverse as—I mean I haven’t seen this in a little bit— but as diverse as [Mel] Bochner, and Moyra [Davey], and Walead [Beshty], and Jim [Welling], and I’ve always liked those Christian Schad photograms quite a bit because his photograms deviated from everyone else’s photograms, because they never held a rectilinear shape. They were always these odd-shaped photograms, and I don’t know why they were, but I think that they’re an aberration within photograms in a way that, as you’ve pointed out, my work has gone to the frame on the floor. They’re no longer rectilinear either.

Williams: I spent some time looking at the artists who will be in the other half of the show that we were just talking about.

Deschenes: They’ll wonder about why all these people are being held together by the word photography.

Williams: I guess that’s the idea, of it being expanded.

Deschenes: Yeah, expanded into sculpture, expanded into video, expanded through research. Most of these people have studied photography.

Williams: Right, I guess that’s the question of what photography is, through its history, and what it’s transformed into, and how it’s become ubiquitous and something other than photography, perhaps, just by way of being ever-present and integrated into all these devices. It is something else, but it’s something else that is not really named, or maybe it’s just that photography’s been lost and rolled into the broader digital culture as its primary site of existence. But while that’s true, there still is this thing called photography that exists and it is still primary and it is still investigated as a singular thing that leads into other disciplines—it can lead into digital, it can lead into sculpture, it can lead into…

Deschenes: Film, video, performance…

Williams: It’s interdisciplinary.

Deschenes: I think it’s photography once again as receiver that makes the most sense to me, and the fact that I do teach and have taught in interdisciplinary programs. Without talking about the document, photography imbues all the other disciplines, and vice-versa. I’m deeply interested in photography’s front/back relationship with all of the disciplines, and hopefully the show will reveal a selection of that, because I don’t think you need to be working with photographic materials in order to talk about photography.

Williams: For sure. I mean from my understanding of its function and technical considerations, there are so many other things in it, like the properties of light, the electricity that operates a digital camera or operates a shutter. A tripod is acting against gravity. It’s an elemental thing, and I know you’ve addressed it…

Deschenes: I like thinking about the tripod, the three-legged apparatus that really doesn’t exist.

Williams: Like in nature. Or in H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds, the tripod is the alien thing because it has three legs.

Deschenes: Oh that’s interesting. I guess I should know this.

Williams: I don’t know etymologically, but the idea of the tripod must have existed before this. When something has legs, it is a standing creature. It has an anatomy, like a camera has an anatomy that can be dissected. We engineer some of these things in our own image, but at the very least we name them after our own image and physiology or like the half-moon I showed you, it’s coming from our experience of the cosmos and the universe and I think that’s the logic of engineering and ourselves, that we make things in our own image, or in an image of the universe. I think making a photogram of the night sky is doing that in a very direct, very literal, very photographic way. You’re making it, but of course it isn’t a representational image; it’s an image of this effect of light that the perceptions of the paper are keyed on, but we’re not necessarily keyed on it to perceive it. Have you ever made a hologram?

Deschenes: No I’ve not, no.

Williams: Okay well it’s like the way a real hologram is made—I’ve never done it either—but it involves a laser and a beam splitter.

Deschenes: But of course.

Williams: If your red laser goes through a beam splitter, it’s still the same frequency of light, with two lasers. One of them reflects off of an object—it’s really just light waves reflecting—and the other one strikes a holograph plate. And then those two, like ripples in water, interfere, and the interference pattern is the thing that’s recorded on the plate. And so it’s just a pattern; it isn’t really an image. So thinking about your photograms, they’re just a pattern; they aren’t really an image. And then of course with a hologram, in order to see an image, you have to illuminate it with a third laser. So you have to strike the plate with another laser. You’re recording a pattern that isn’t necessarily projected, but maybe it could be. I guess that’s the extrapolation I thought of when I started analyzing what it means to record something that can’t really be played back. Because it is so direct. It’s a representation but it’s not a representation for our perceptions, it’s for the paper’s perceptions, and we can see it, but we might not necessarily understand it.

Deschenes: That’s really nice. I think you’ve done a really good job talking about things, about the work in terms of the machines that we make. I think it goes back to our earlier conversation about [Étienne-Jules] Marey. In response to your generosity in thinking about terms for my work, I think that looking at the smoke machines that he made might have similar…

Williams: [looking it up] Movements of Air?

Deschenes: Yeah, I call it the smoke machine. You haven’t seen these?

Williams: No, I don’t think so. They make me think of one of my photographic mentors, who I studied under, David Goldes.

Deschenes: Sure, sure.

Williams: He would surely know these. They look like the record of a pattern, of the air and the smoke, and it’s turned into this other phenomenon that it’s recorded though you may not necessarily know how it’s acting. It’s really just the act of observation at this stage. It’s leading to the study, the study isn’t complete. It’s the first record. Now that you have this still, now that the phenomenon is paused, you can make a closer analysis of, what would it be, the convection and the undulation of the air and the smoke. It makes me think of Bernoulli’s principle, the most basic statement of a flow of fluid, I mean I always thought it was air, over an aerofoil, creating lift.

Deschenes: I want to say his documents were intrinsic to pre-aviation physics, but I could be totally wrong.

Williams: That was the moment… I wanted to ask you just a couple more questions in conclusion. I wanted to ask you about teaching because I remember you saying that you taught a research class at Bennington.

Deschenes: Yeah, I teach a class on how artists do research, versus how everybody else does research. Obviously, artists don’t have the same set methodologies. When artists do research, it’s not literal, it’s contingent. It’s something that has to happen in order for the work to have any relationship beyond itself. So yeah, I teach basic ways that artists go about that. I started this term by asking students to look at Robert Barry’s question of what exists beyond the frame. And then Lucy Lippard is going to be coming next week, and she actually utilized the Robert Barry question in her own curatorial projects. I didn’t even realize that they started with that prompt.

Williams: In a talk I saw, you mentioned this idea of doing the research and not presenting it directly.

Deschenes: Yeah I try really hard not to have students literalize the research they’re doing in the work. That’s a longer procedure that doesn’t happen right away, that happens through a lot of trial and error. The place where I teach began with Dewey’s philosophy. When I was at the Walker, someone asked me if I could think of a philosophical counterpart. Certainly, it would be him. And certainly—I know I’ve talked about this a lot—in terms of curatorial practice, Alexander Dorner is somebody I’m still really interested in. He wouldn’t put work together from the same time period. He worked with somebody like El Lissitzky to come up with the Abstract Cabinet (1927-28). And then when he taught at the place where I’m teaching right now, he would teach with the poetry and drama faculty, completely unexpected colleagues.

Williams: So again, it’s the interdisciplinary idea.

Deschenes: Absolutely. I was on a panel recently, talking about the Thomas Walther collection [at MoMA], and it was interesting because Richard Benson was saying—I think Richard Benson’s work has been remarkable. Do you know his work? He taught at Yale for a long time. He did a show at MoMA [The Printed Picture] showing the history of print technologies. Supersmart guy. He was saying how much he doesn’t like interdisciplinary education because he thinks it allows students to not become knowledgeable about anything. In my experience, that hasn’t been true at all. I think it allows for an intersection that is infinitely more interesting than the silos.

Williams: Since we visited the Sturtevant show together, I wanted to bring her back in, perhaps in just a brief way.

Deschenes: I think the passageway that they established at MoMA was remarkable.

Williams: With the running dog.

Deschenes: Yeah. I think that that piece [Finite Infinite (2010)] of Elaine’s has all the things that I want work to have. It repeats itself, it plays back on itself, but the experience is never the same. Your experience of it is never the same. I think part of that is that you’re traversing space while you’re viewing it.

Williams: Even over that abbreviated walk, you do change, in a minor way. The viewer’s the part that changes.

Deschenes: The viewer is changing. You can see yourself changing over an abbreviated period of time. And there’s also the fact that that piece is covering up what is usually a window. Starting with a threshold, with the keystone as threshold, and now ending with Elaine’s piece, I think is perfect.