Interviewed by Jonathan Thomas

Jonathan Thomas: Given the range of your work, which includes the design of landscapes, environments, sculpture, furniture, performance, and jewelry, all informed by an eclectic array of historical references, I’m not sure there’s an ideal place to begin. But how about with Donald Judd? After he moved to Marfa, Judd devoted a good twenty years to designing furniture. In his essay, “It’s Hard to Find a Good Lamp,” he said that the art of a chair is not to be found in its resemblance to art, but rather in its usefulness as a chair, that unlike art, furniture was fundamentally defined by its functional nature. For this reason, he claimed, art was unable to become furniture, and vice-versa. Since a fair portion of your work blurs the lines between sculpture and furniture, I wonder what you think about Judd’s position? Was he a point of influence?

RO/LU (Matt Olson): We do have a sprawling set of interests that find their way into our work. I have a hard time describing RO/LU to people. I like to refer to it as an open practice, as I want the work to come to us rather than deciding in advance a set of goals or inquiries in any fixed sense. I haven’t had good luck in life when I decide to do something. My ego always ends up involved, a desire for approval, fear… I’m a wreck! :) My inner dialogue is very Woody Allen. But if I stay out of the way and just pay attention, something else becomes available. And then I don’t care where I begin and end versus an idea or a collaborator. These things are happening, I’m participating and things are emerging. It’s not mine. A classic Judd quote! I love his work, but often his views seem to lack a humility that I want at this point in my life. There’s too much certainty there. And I love that quote too! I love thinking about something that resembles art. We explored this with our residency, When Does Something Become Something Else: The Apparent Is The Bridge To The Real, at the Walker in 2012. But, to assume that Judd knew what art (or furniture) was when he wrote that is too much of a leap for me and seems to forget time’s role. Everything is changing all the time. He was a massive influence but not in any literal way. Perhaps more like how a piece of music is an influence? It can have a massive impact, but it would be hard to pinpoint. I don’t mean to make light of him though and don’t want this to sound dismissive. His work is among the most beautiful and inexplicably perfect as any I’ve ever seen.

Thomas: I agree with you about Judd and I confess I was putting him out there as a potential foil to get things started. I mean, one can sense an affinity with Judd’s furniture in some of your projects, at the level of geometry and materials, but your practice does seem determined to move beyond the more prescriptive parameters of definition that he was fond of defending. Another option would have been to cite the functional sculptures of Scott Burton, who you referenced with your first body of work in furniture, Field Recordings Made from Wood (2010), and then again with Setee x Three (after Burton photo, “Public, Private, Secret”) (2012). Unlike Judd, Burton was keen to break down the boundaries between art and design and thought of his furniture-sculpture hybrids as working to that end. I would like to discuss your sculptural furniture, but I think you give us a hint when you say that you have an open practice and that everything is changing all of the time. I wonder if the thinking of John Cage has influenced your outlook?

Olson: John Cage is my imaginary friend. And hero? Though not in an ego/hero sort of way. He’s like nature to me… I mean, he represents giggly humility, gentleness, and patience as resistance, but with glimpses of absolute clarity. Rauschenberg and Cunningham must also be mentioned here. Jonas Mekas comes to mind, too, as a non-ego hero. Like a life that is someone else’s but becomes a wave through which you get to feel and understand whatever self there is. And the joy of curiosity and temporary discovery that I think Ray and Charles Eames had at times. Pete Seeger (because of my dad). Robert Filliou. Franz Erhard Walther’s exploration of different avenues of knowledge (The Body Decides). And why are these all men? So many women too. Sophie Calle, Louise Bourgeois, Katherina Seda, Carmon Argote, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, Anna Sophie-Berger, Yvonne Rainer, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Mary Manning, Laura Brunelliere… I mean I could weave a cocoon-like collage that I think I’m walking on and sleeping in when we are working, and Scott Burton is definitely a structural element. Burton’s work came and got me in 2007 or so. I just didn’t know what I was looking at sometimes. Big stone chairs that seemed and felt super punk rock to me. It was the first wave of the digital photograph becoming the largest part of my… garden? That sounds stupid, but I don’t know what it is :) I would see these images of Chair 1 & 2 (1986), for instance, and not really understand what I was looking at. We started making what we thought we saw out of really accessible materials: plywood and pegboard and concrete. And so it had to do with having too much to talk about, and it keeps changing anyway! Burton, Judd, photography, the internet, blogs, the deep craving for an anti-ego streak and a resistance of capitalism? But Cage? I fall in love with him almost daily. And Louwrien Wijers!

Thomas: Nice. I like this idea of work coming to get you. It almost sounds paranoid, only it’s not. It’s the chance encounter. The anti-ego artists you mention are key. They really moved the conversation away from the subjective drama of Abstract Expressionism, as the terrain shifted in the ’50s and ’60s. There was a similar impulse at the same time in Europe, in literature for instance, in the work of Robbe-Grillet and Nathalie Sarraute and the emergence of the nouveau roman, which broke from the unified consciousness of character and plot and the emphasis on the individual that had dominated the French novel since Balzac. This period concern with de-subjectivization was at the heart of Cage’s philosophy, based on his encounter with the work of Marcel Duchamp and composers like Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez—it was played out in his use of chance procedures and indeterminacy in composition, which had a huge influence on a wide range of artists associated with the interdisciplinary neo-avant-gardes of the 1960s, which you seem to be drawn to. I sense that you channel some of this energy and humility with RO/LU, even in your responses here. Your mention of accessible materials reminds me of Enzo Mari, who you’ve also cited. In the early 1970s, as a socially-minded designer working in the face of economic disparity, he democratized his pursuit when he gave his furniture designs away for free, to enable people, to enable craftsmanship. All you needed to build the designs collected in his Autoprogettazione (1974) was a hammer, wooden boards, and a box of nails.

Olson: “Design is only design if it communicates knowledge,” he said. Olson: “Design is only design if it communicates knowledge,” and knowledge is… hmmm… so many things. Knowledge is communicated by everything! I like Mari lot, and his Autoprogettazione project is great. We discovered it after we started building furniture. It felt like a signal. This was like 2007? A green light. It connected to the Whole Earth Catalog vibe we were into and Eastern philosophy stuff I’m always falling forward with. And yet I get nervous whenever anybody starts making proclamations that feel like absolutes. And Mari does that :) Even the way you describe the past in the first part of this exchange turns my radar on. I try to bring forth a caveat that whenever knowledge is present, non-knowledge is also present. Then I can breathe again. Like water. I always trust when someone else has done almost the same thing as we’re thinking about doing. We had a crazy experience with that regarding Scott Burton and Oscar Tuazon actually! Long story though :) For me, there is a really significant symposium that happened at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1990. It’s been the source of much of my energy since I learned about it in 2002 or so… maybe? Who can remember? It was initiated by the Dutch artist Louwrien Wijers. Rauschenberg came to get me through that. I know it’s not true and yet, it happened so. There I was living in his house. There is a set of five documentaries about that symposium, each an hour long, about the panel discussions and the participants: artists like Cage, Chamberlain, Weiner, a young Abromovic; scientists like Bohm, Sheldrake, Ilya Prigogine, Francisco Varela; and spiritual leaders like the Dalai Lama and Raimon Panikkar. I watch them over and over. They keep changing. Anyway, Rauschenberg, when asked about his process, said “I am following the process and the process is following me. And there’s no separation. And we are both bewildering each other.” That struck a chord with me that I guess I still really appreciate.

Thomas: I appreciate your questioning of knowledge and what you say about non-knowledge and I agree that knowledge is communicated not only through language with prose but also through the pleniof sensorial experience. Lucien Castaing-Taylor and those associated with the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard—Ernst Karel, Véréna Paravel, J.P. Sniadecki, and others— are doing really exciting work on this front, with sounds and images, and in the realm of nonfiction cinema. Leviathan (2012), for instance, takes us to the forefront of cinematic research—its immersive qualities plunge us into a world of sense perceptions, but the knowledge it produces about the experience of commercial fishing cannot be presented in prose in a fungible way. But just to clarify, I didn’t mean to speak in absolutes earlier; instead I was trying to sketch a historical trajectory, because I do think it’s important to see how ideas develop and travel across space and through time, and how they’re impacted by events and struggles and encounters in the world. For instance, it’s probably fair to say that the development of an anti-ego approach in the arts in Europe and the United States had not only to do with an emergent interest in Zen Buddhism, but also, or maybe because of, the experiential catastrophe of World War II. This was a major theme in the writings of Theodor Adorno, for instance, prior to its elaboration in the 1960s. In any case, a lot of your projects seem to develop from encounters with figures or thoughts or projects from the past, from encounters with photographs or videos, often by way of the internet, although I know you also spend a fair amount of time in libraries and archives. You’ve said that you use art and design history as material in your work, rather than as a source of knowledge or inspiration, and I wonder if you could describe and give an example of what you mean by this, by art history as material?

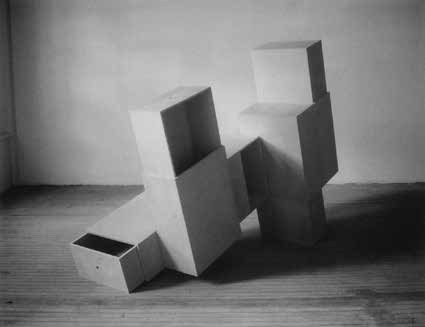

Olson: Mari seems to speak in absolutes frequently. He’s very dramatic! It’s super seductive actually. I love it in the moment. I remember when he hollered out at Rem Koolhaas: “You are a window dresser. A pornographer.” And he can get away with it because he’s the kind of person who can get away with it, because he’s sort of adorable as a cigar-chomping Italian character in a worn out lambswool sweater. A grumpy wizard. (It makes me wonder about Judd getting away with so much certainty? Maybe there’s a principle vs. personality layer at work?) I wasn’t saying you were speaking absolutes. I’m probably overly sensitive about the presence of certainty? For me, history is a living part of the present. It feels like history comes to me in the moment. That’s why I love the internet. I feel like it’s liberated history from the linear, time-based lens we generally use. It’s exciting. There’s a bunch of different “as” propositions we like to play with: Learning as sculpture. Attention as place. Making as thinking. Doing as seeing. Participation as performance. It all started with sitting as seeing, I think. And art history as material is not a rather than, it’s in addition to knowledge and inspiration. We often take pieces of geometry from existing works. Guy de Cointet’s sets, for instance. Scott Burton. Fragments that are literal. But when people asked us what we were doing, we didn’t really know. It wasn’t appropriation. We called it art history as material. It feels right.

Thomas: Mari’s great. And I love your list of x “as” y propositions, which seem very generative. I’m also really interested in Guy de Cointet, so I’m happy you brought him up, partly because I want to transition into a discussion of your own forays into performance and publication making, but also because he gets at what I was trying to express previously about language and knowledge. I mean, his use of language, whether in painting or drawing or performance, is more sensual than semantic. He uses language as material in a way that calls to mind the Ursonate of Kurt Schwitters or the word salads of Tristan Tzara, or on the page, his compositions invoke the material qualities of concrete poetry. But when we enter his world, what initially begins as cryptic and opaque eventually takes on meaning. After moving from Paris to New York to Los Angeles, where he arrived in 1968, he began making these strange and beautiful books. Then in the mid-’70s, he developed his theater as a way of explaining the books, but not in any conventional way. The sets he designed resemble art exhibitions with their colorful universe of makeshift geometries, of numbers and letters as graphical objects, and these props became the means of enacting, through performance, the structural and arbitrary qualities of language in a way that remains, nonetheless, very funny! His work is very beautiful. And what I appreciate about your work is the way it invites us to revivify and discuss so many important figures from the history of art and design. I know my previous questions were concerned with your approach to sculpture and furniture, but like Guy de Cointet, or perhaps like the Eamses, you also shift genres and landscapes and materials as a designer, or as an office, and so much of your work is about process and collaboration. It’s as if you’re constantly experimenting with ways of extending perception. On this note, I wonder if you could say a little bit about your involvement with High Desert Test Sites?

Olson: I love what you wrote here. Thanks. Truly. Yes… more sensual than semantic. I am happy now! The act of shifting genres or landscapes that you mention is really what makes it work for us. I think it’s how we keep falling in love with these aesthetic ghosts we’re chasing. How successfully can we change our minds again? And Guy de Cointet. Total lightning bolt for me, and a lightning rod for our work. There’s an important story Larry Bell told. Guy was his assistant and didn’t speak English, so their communications were… more sensual than semantic? Anyway, Larry noticed that Guy was filming the elderly women across the street from their studio. She hung her underwear and shards of tinfoil she cooked with on a laundry line outside her home. Guy was getting geometry for his work directly from her. Larry said Guy seemed to think it was coming to him in some kind of code. That feels really familiar to me even though it sounds crazy when you say it out loud here. There’s another important Guy story for RO/ LU. In 2010 we were recreating the set for his A New Life (1981) in the shop. It was a self-initiated project so there was no budget. And it was really hard! I got kind of mad about something and hollered “what the fuck are we even doing this for?” in frustration. Sammie Warren, a former RO/LU family member, said: “We are learning from these things in ways no one could teach us.” And that’s a sensibility that is so important to RO/LU. The HDTS project! Wow. I get tired even thinking about it. It was a two-mile-long by five-foot-wide white line through the desert, across the road from Andrea Zittel’s A-Z West studio. We worked with our friend Laurel Broughton, who’s an architect in LA. She contributed the white triangular forms that are interspersed throughout the space. She has an amazing studio called WELCOME PROJECTS.

We’ve always been interested in land art and the fact that most of us only see it through photography, and what that means about it, especially in light of the way the photograph seems to have taken over the world. We were interested in something Allan Kaprow said about not being able to talk about something unless you’d actually done it. There were a lot of ideas swirling around. But it was what Mike noticed that, so far, has been the energy we took from the project. While we were building the work, in sweat-soaked shirts with tool belts and water jugs, people from the community seemed super interested and excited to talk to us about what it was, why we were doing it, etc. When it was done they viewed us with suspicion and a vibe that was sort of like fear. It’s been huge for us to think about when art might or might not be alive. A big part of our residency at the Walker was based on exploring that.

Thomas: Would you consider your projects, whether objects or actions, life forms capable of telling their own stories? I remember a conversation we had, when you told me about an exhibition Anthony Huberman had organized. Do you recall? What you had to say about objects was interesting.

Olson: I can imagine that conversation, but I don’t recall. I think they are capable of telling a story but not the story? It’s ocean-like for me. Changing. Mixing together. Something is coming undone so it can become something else. We make them and they make us.

Thomas: Yes. I think we were talking about approaches to organizing objects in space, and how objects possess their own energies and histories, which intermingle with our own subjective histories and what we bring to our interpretations of them, but that they are capable of suggesting their own connections, their own stories, or perhaps their own vibrations, which are independent from the narratives we may want to impose on them, through logic. There are so many more things we could discuss, which I attribute to the generosity of your practice and its willingness to establish connections. But I wonder, what sort of genres and landscapes and collaborations are you working on now? And are there any you are imagining, but are yet to explore?

Olson: I do remember that conversation now. And yes, there’s a short Anthony Huberman piece called “Take Care” that talks about this phenomenon. I love it. We (RO/LU) are working on a whole bunch of interesting things right now. And RO/LU has never had a better group of people. There’s a large 50 years of Superstudio show that’s starting in Milan this fall that we’ll be involved in. We are making a piece for a Le Corbusier show at the Swiss Institute in New York. We recently designed a restaurant, which was fun. We have a few projects happening with some large institutions, which are also fun to watch as they come to life. I really am so grateful to have found some space to explore. Memory, publishing/sharing, love and nature. I hope that’s what my life is in the future. I hope RO/LU can behave like water. And surprises!