Interviewed by Kenneth White

Kenneth White: Can you tell me more about the circumstances of getting Snows (1967) organized? Were there any difficulties with Experiments in Art and Technology?

Carolee Schneemann: They didn’t work with me, no, this wasn’t their project. Because Billy Klüver was very fond of Jim [James Tenney], and Jim was at Bell Labs, I had access to wonderful technicians who were excited and willing, but as usual, I felt that I was sort of sneaking in on the margins of Klüver’s friendship for Jim—he really didn’t care what I was doing. So it was a bit of a token towards Jim. And since I always feel that my work is under-par, that it’s not up to whatever the formal expectations are, I can do what I want and I don’t expect it to be celebrated.

So there were no complications with the technicians. I told them what I saw and we tried to decide—how could it happen and what would it cost? I had a couple of wonderful assistants, one was a techie who could help envision the circuitry, how the electronics would actually work, from the seats, and we also had microphones under the stage, to magnify the thumps and the falls, and that was an important counterpoint which had to do with including chance contributions, because this production was blessed with huge chance gifts. For instance, at Christmas, I had seen Gimbels department store covered in these snowy branches and I thought, I need those, I need those! I knew I had to have a snow environment and that it was going to be produced in January and that I wanted to fill the space with a snow-like collage. And so a couple nights before we had to install, I went with a crew around the back of Gimbels, where their trash was, and there were all my branches! Just waiting there! We gathered all of them up, and as we started walking back on 33rd Street, it began to snow. I felt blessed and confirmed in all this. In the mean-time the owner/director of the little theater, Paul Libin was fiercely against the Vietnam War and so he decided to give me the theater free for an incredible amount of time, two or three weeks, to build in it, to do what I needed. (Now what this had to do with the strange sex calls that started happening at 2 in the morning…)

White: I don’t know anything about this.

Schneemann: Oh, well, yeah…

White: What happened?

Schneemann: Strange sex calls started to happen at the loft.

White: Which loft?

Schneemann: On 29th Street. I think it was still the old loft. 122. But some man was calling many nights and breathing strangely and I kept thinking, oh I hope it’s not Paul, who had given me the theater. But I have my doubts. Anyway, he was wonderful. I built a soft foam environment. The audience had to push through the foam to come in, to enter the theater. It was very dark when they came in and there were luminous lights on the snow-branch environment. So it was a huge amount of work, huge to organize. I had some remarkably devoted, sort of obsessed workers who would try anything, and they were wonderful. I was able to inspire that. We worked like crazy to build the installation, to organize complex materials. Also, I had this same sort of mystical magic in finding some of the projection film that I wanted.

I needed some early Nazi film to give a layer under Vietnam, and I found those Bavarian skiers. They just had this great macho heroic aspect of secure domination, skiing through space, and that became one of the energies, the skiing figures, juxtaposed with the Vietnam con-figurations which were collapsed, in despair, wounded, burning, drowning, running …

White: So this Bavarian ski film was projected as well as Viet Flakes (1965), onto the—

Schneemann: Bodies, onto the live performers. But in sequences. They weren’t done at exactly the same time, that wouldn’t work, so I also had, I think with the Bavarian skiers, I also had Red News simultaneously, that magical little film that I also found mystically by closing my eyes and putting my hands up in front of a whole wall of 16mm films and I just pulled it and it was this perfectly remarkable compendium of disasters, a little feature that they showed at contemporary movies, Movietone or something, and it was just one disaster after another. A boat blows up, motorcycle racers blow up. It was very satisfying, one explosion after another, and then it cut to Santa Claus appearing for the American Legion.

White: So did you make a master reel for the performances explicitly?

Schneemann: Oh yes, but there were several reels and they were all separate.

White: Where are they now?

Schneemann: I have them somewhere. I had four projectors around the stage, so I had to have people loading them, starting the projectors, stopping them, making a simultaneous projection of two or three and then letting them conclude.

White: This reminds me a little of Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable (1966), his multi-sensory projection works that he was doing with The Velvet Underground.

Schneemann: And VanDerBeek. He was a friend who was doing simultaneous projections, I think at the same time. VanDerBeek filmed me doing the parachute dance for Oldenburg in Waves and Washes. What year was that?

White: 1966.

Schneemann: I have my years jumbled up. It might have been after I did Snows. Who else? Jud Yalkut, who shot everything Charlotte Moorman ever did. He lived in Ohio. He recently died. He was a great documentarian of Charlotte and other events of the time. But it was in the air. It was the ’60s and everything was happening everywhere all the time. But my interaction with the audience was unique. I don’t think anybody had done that yet, or had heard of it. There were actions which led the performers across planks layered between the audience seats. These walks were often undertaken practically blindfolded by wrapping the performers in a silver foil. Sections of the foil might fall into the audience, so they were on alert since the walkers were in a shaky position.

So, of course, the whole performance was structured by the uncertainty of the shifting cues, and that was important, to keep us responding in the moment, to each other and to the media.

White: Can you tell me more about making Viet Flakes?

Schneemann: I was gathering all the images because, as you know, the Vietnam War was very suppressed. Jim and I found out about it really early, in 1961, in Illinois, through a poet from Vietnam, a young woman who told us that we had troops in her country, destroying villages, arresting people. We had never heard of this. Viet-what? So I started research early by gathering from international news and alternative papers and various things from the ’60s, and then finally from a really important publication where I found a great deal of my imagery, Report From Vietnam, which was a compilation of photos by major photographers. And I reshot those. I laid them all out, I gathered them, some of them were only Xerox, and I had them all organized at the loft on the floor.

I had borrowed a camera from Ken Jacobs, but it had no close-up lens, so I was beside myself. This was the only day that I had the camera, and the film, and that I was able to concentrate on this work. So I went to 34th Street at 6th Avenue, where we still had a 5 and 10, and I bought those little magnifying glasses that people use when they can’t see the newspaper. I bought three or four of them and then I could tape them together and move them in and out, over the photographs, as if I had a responsive lens.

White: I’ve always found that fascinating, such a handcrafted and intimate way of connecting with these photographs that come from so far away. What I found so remarkable about Viet Flakes was the way that you reinvigorated a life and an energy into these photographs and made them even more intimate and, in a sense, found a way to break through the mediation. So even though all these images were coming in, they were still coming in by way of commercial means, through television and through certain conventions of media.

Schneemann: It was as intimate as I could make it, as it was with Terminal Velocity (2001).

White: It seems to me a direct connection. It’s Viet Flakes and then something like War Mop (1983), where you’re trying to pound sense into the television, trying to cleanse it in a way, through very quotidian means, through the very modest manner of a mop. And then to Terminal Velocity, trying to rearrange the photographs, to give life back to the victims depicted.

Schneemann: The work was domesticated by the impropriety of the materials and the complete lack of technological security. But that helps me in my work, that sense of desperation. How can I do it? It hasn’t helped the appreciation of the work because it always looks unfinished or crude. But it offers another psychological dimension. It’s less of an artifice, less removed.

White: Where does the term “Flakes” come from in Viet Flakes?

Schneemann: From the falling snowflakes. Because the war was so endless and inexorable. We were bombing every day, everywhere. It just never ceased and had no release. The militarists were producing at the height of their potentiality, and there was no moral consideration or implication whatsoever in the popular consciousness of this endless bombardment. Village after village, mountain after mountain, towns, farms, it’s the same pattern that’s still being enacted on Palestine, and variations I guess, in Syria, in Uganda. It’s such a brutality with no release. There’s no return consequence. Sorry, we had to obliterate you so that you can exist. We had all those sayings in the ’60s.

White: Burn the village to save it.

Schneemann: Yes. So it goes right now to where we are with imposing this depraved morality, as if all the punishment it implies is valorous, deserved, and it’s very indirect. It’s a transposition that’s completely out of whack, because instead of driving your car into a tree or beating your wife or shooting yourself up with heroin, you get organized so that you begin to belong to a righteous system that can impose brutality and decimation and feel completely justified that this is biblically ordained, like Romney saying the land is here for us to exploit and control, and Santorum believing that every ovary seed is a potential sacred human life that must be brought forward no matter. And that’s amazing. It’s not just short-sighted, it’s a kind of fanatic righteous certainty that can exclude reality. And saying that Planned Parenthood is about abortion. It’s about pap smears and getting your menstrual cycle fixed and having your breasts examined. The least of it is abortion. So they’ve thrown everything out that women desperately need.

We had a terrific Planned Parenthood center in New Paltz, so all the women in the town had access to their facilities, which were so good, and now they’re closed. Kingston is closed. The only Planned Parenthood that’s left is in Poughkeepsie, and of course it’s overwhelmed. Now you go there and you have to sit for hours. They don’t know where your records are. The people you’ve worked with have been fired. It’s a very pervasive hardship.

White: When these politicians make such proclamations about what women need, and what they should need, and what they deserve, and how their lives should be run, it’s unacceptable.

Schneemann: We’ve been fighting this since I was six years old and a hundred years before, and they’re back, the autocratic patriarchs. They did not soften, they did not dissolve. They’re more crazy because they’re lunatics now. Because they’re so outside of the transformations in the culture.

White: And still enough people listen to them and they find support, enough money to amplify their voices. Like Rush Limbaugh.

Schneemann: Or the Koch brothers. Or that Adelson in Las Vegas. And they’re all fanatic for Israel, at the expense of everything in the Middle East. They would blow everything up to sustain their control over oil. Plus resorts, landscapes. The best golf courses are in Tel Aviv now. You see the contrast in the walls the Israelis have built, confining and constricting the ancient Palestinian farms and olive tree orchards, and then on one side of the wall, there’s a luscious, manicured spa and golf course. It’s the Americana fantasy. An investment. You should see the brochures. Investment possibility, come to Israel! And it’s all happening on the appropriated land.

White: Can you tell me more about when you left the United States and went to England? That was in the early ’70s, is that right?

Schneemann: No, ’69. Did you read what I’ve written about it?

White: Yes.

Schneemann: What did you read so far?

White: Well I understand your relationship with Jim Tenney came apart and you were upset by the political and cultural climate in the United States at that time. You decided to leave for London. I can’t remember exactly what opportunity was there for you.

Schneemann: No, I didn’t decide anything. I had a love affair, Jim and I had split, and Jim and I were both so sure that we had built something so strong and inevitably consequential, that whatever happened next would carry what we had been and done. And so when it didn’t, and it fell apart, and I was betrayed and lied to and cheated on by the love affair guy, and I had lost Jim, I think he had already married, and everyone was being killed or dying or suiciding—the world was one assassination every morning, I was flipped out. I was dissociating. I was not functional. It took a couple hours to put socks on if I could find them. I didn’t quite know who I was, or where I was, and I couldn’t live here at the house all alone without Jim, so I rented it to a young couple. I thought they would be okay.

I didn’t like him, I didn’t trust him, but he had a grant and he needed a quiet place to work. I liked the young wife. They turned into monsters. They turned into a kind of Charlie Manson group here in the house. Everything’s destroyed finally before they leave. The banister is chopped out and thrown into the stream bed. My books are stolen. All the antiques from Jim’s family and mine are stolen—they were locked up here. There’s a huge printing press, huge, left on the porch. Everything’s greasy. They’ve destroyed my work. You find the shards of all the glass work I was building at the time. They write my name in shit on the walls. It was a nightmare. And all the windows are shot out, and the furnace burner had been left to burn itself out. It’s a nightmare, it’s a disaster, I have no money, I can’t get back, I’m dreaming this. I’m in London, I’m barely recovered from this break-down and I’m dreaming the destruction of my house. And the wife, the young wife who was there, writes me a letter saying she’s sorry, it was out of her control. So I don’t know the extent of the damage, and then the neighbors who had been my friends become the evil conveyors and supporters of these deranged hippies. They helped them move the furniture and my books and everything out of the house. What happens when I finally get the police here is they say, Are you an artist? Yes. Are you female? Yes. Are you divorced? Yes. Do you have a regular job? No. You’ve put these people in your house? Not exactly. There’s nothing we can do for you. You are culpable in every regard that we will note. So the real estate person is trying to steal the house from me. She says I owe her all this money. And it was endless destruction here.

It’s an unbelievable wreck and they left garbage and trash and needles from shooting up. The house is a nightmare and I can barely get back, I’m dreaming it. Finally, I rent enough showings of Fuses (1964–67) and get a ticket to come back to the States. I come to the loft in New York—no one knows I’m coming; I just got the ticket because I had to get back, I have to get to the house—and my neighbor downstairs says, oh Carolee, your friend came today and he left his suitcase. I say, friend?What friend? Nobody knows I’m coming back. He says, yes, he’s traveling. He wants to see you. But who is it? He didn’t say his name. What does he look like? Very nice, he looks very nice. And I say, well when is he coming back for the suitcase? And he says, I don’t know, I don’t know, he’s in the park. What park? He went to Central Park. He says you should go there. But I just got back! He doesn’t know I’m here. Where in the park? He said he’s on a bridge.

So it’s so crazy, it’s more than Alice in Wonderland, it’s deranged, and it’s spring, so I go to the park, Central Park, and I start wandering around. I don’t even know who I’m looking for. And there on a bridge, I see my sweetheart from Minnesota, Charlie. My mystical woodsman Charlie is sitting on a bridge, which he can do for hours. Charlie—he’s a mystical woodsman.

White: What’s his last name?

Schneemann: Berg. He’s Danish. He died. Smoked too many Camels and drank too much. I loved him. So there’s Charlie sitting on the bridge, and I say to myself, I have a savior. This is beyond amazing. So we start making love on the bridge. I haven’t seen him for two years. He appears to me when I’m injured in London. He’s part of many mystical things, Charlie. So there he is, it’s probably 1969 and he’s on a bridge in Central Park and we go back to the loft, which is also sub-let. And he calls Molholm, the bad lover, he calls Tom. Charlie’s incredible. He’s just got this slow magic. He’s smoking a pipe, and he’s very handsome, like a Western movie star, and he starts talking to Tom. And I say, I don’t think you should do that Charlie. I don’t think Tom wants to hear from us. And Charlie says, no lass, it will be fine. Then he comes back and says, Tom will let us take his car to the country. It’s some old Cadillac. So next thing we’re in Tom’s old car and we come here and it’s just as bad as I’ve described, and I’m in tears, and they’ve stolen all this stuff. They’ve stolen the potbelly stove, and my rugs are gone. Charlie’s comforting me, saying we’ll fix it, don’t worry, I’m here, I’m helping. So we get some food and we clear a table with all this garbage and rubble, and I tell him what’s missing. The next day he says, I’m going to town, lass, and I’ll get some of your things. I said, but how? What are you going to do? He said, I’m going to go to the pool hall, to the bar, I’ll go around. And I say, Charlie these are very evil dangerous people, they’re completely crazy. They’re capable of things we don’t even want to think about. He’s lighting his pipe and tapping it down. Don’t worry, I’ll be back in a little while, and I’ll bring some sandwiches. So I start cleaning up and moving crap, and two hours later a truck arrives, and in the back of the truck I see my ancient potbelly stove, and the green rug. And Charlie and some guys saunter out and he says, this is Bob, and this is George. They were helpful, they had some information. They’re sorry about what happened. So he’s restored it. He’s this miracle creature. He’s just so wonderful. He’s also very traditional. He’s very masculine. The old hierarchies are very strong, magical and mystical, and that makes him very powerful for helping when I’m in this trouble. He’s got it all smooth. We find the banisters down in the stream bed. We start drying stuff off.

How did I get to this part of the nightmare? Where was I? Why did I go to London? I didn’t choose to go. Clayton Eshleman was in the loft, trying to look after me. In Plumb Line (1968–71) it describes how they’re trying to feed me these dead pieces of things that are all dried and useless. He’s reading my mail and he says, you’ve been invited to Cannes for a special program for Fuses, and here’s a ticket and a hotel promise. And he says, you can’t be worse off there than you are here. So, I have to pack up Kitch, prepare her for travel. I take the Plumb Line mess in another satchel, my cat, clothes, I sublet the loft real fast, and I leave. I go to Cannes and it’s crazy. That’s where they tear up chairs, the seats, with knives when they see Fuses. It’s not porno. I’m with Sontag and I ask Susan what’s happening, because she’s sophisticated, and she says, I don’t know but we better get out of here—after they do the chairs they might look for you. And then I have no money, and I have Kitch, and we wander around and we sleep under tables and we sleep with an architect at his house, and then I’m invited to Avignon. Somebody gives us a ride to Avignon. I sleep in the office under the table with the cat. Do I go back to Paris? Maybe to the house of this wonderful amazing strange friend, Victor Herbert? […] Anyway it’s a flop house for everybody interesting who leaves anywhere in response to the endless Vietnam War. So The Living Theater comes through. Blood Sweat and Tears comes through. The famous actor—he just died, and his wife was suing for his photos and artworks—he turns up and we were supposed to like each other—Dennis Hopper—and we don’t like each other at all. So we’re hanging out because we’re all trying to get into the one bedroom, which is a mess. Victor never, never changes a sheet or cleans up anything. There’s fur and hair and shoes and underwear and clippings, and all of his investment papers and hairbrushes, everything all in a huge pile. But I stayed there for quite a while. And then, from someone I’ve known since before I was crazy, I get a letter from the States for a very lovely wedding that’s happening in London and I’m invited. Victor gets me a ticket, and a woman I’ve met gives me a beautiful silk Pucci dress to wear. I leave Kitch with the stoned hippies and I take a ferry to London, and it’s magical. I have such a good time. I had boyfriends every day. Everywhere I go. I’m still in that one silk dress and I think, I think I could live here. Paris is closed off and won’t work. So under this complete delusion, I go back to Paris. My cat is completely crooked. Kitch, she’s so stoned, she doesn’t stand straight for many days. They’ve been giving her all the dope they’re smoking. She’s adorable and weird, but she’s slanted. Other things happened, but I go to London with—no, I had to smuggle her, oh no, it’s very dicey. Oh, this is not easy. In Avignon, I met a couple who’s traveling around, Vicky and Bob, and they’re going to be driving to Calais at a certain time, they have a reservation on the ferry. I meet them in a café because I hear them speaking such terrible French. So I go over and say, hi, are you Americans? No, we’re Brits, we’re English. So we chat and they tell me their travel plans and it turns out that’s about exactly when I think I better try to get to London. So I tell them I have to go there and I have a little cat who’s very well behaved and, I don’t know, is there any chance they can smuggle us? And they’re so sweet. They say, well yeah, we could try, sure. So they’re driving a white car and their appointment is for August 11th and I’m to meet them at the Calais drive-in. So I go there and it’s pouring rain, and I’m laying under a bush, the cat and I are under a shrub, we can’t be seen. It’s fucking freezing, I’m starved, I didn’t have enough snacks or something, and I’m looking for a white car with a Vicky and Bob. And I see it! They turn up. It’s a fucking miracle. And we get in the car, and they’re so sweet. I get in the back seat and put Kitch in her basket and I’ve given her a tranquilizer, which I never do, but I had one. She swallows it. I wrap the basket up, put it beneath my feet, put a blanket on my lap. And we’re driving through customs to get on the ferry and I see the blue legs of the official coming to the car, and just then there are paws coming onto my lap, and meowing, and she’s saying, the cat’s saying, I can’t stand it in there, I don’t feel good. And I say, oh shit, the cat is out of the bag! SoI take this scarf and put it over her, and she’s on my lap, and the inspector comes, and I tell Vicky and Bob, the cat’s out of the bag! And they’re so cool, they’re so English. They say something like, oh, not to worry. The inspector comes up and says, do you have anything to declare? And Vicky says—and I’m chewing gum ferociously—I’ve decided that innocent people chew gum and look stupid, and he looks in the back and I’m chewing gum—and Vicky says, I’m so sorry officer, I think we’re over a bottle of wine or two. And she unwraps them and completely distracts him in the front seat. And he says, oh that’s not so bad, that’s okay, you can go. So we go. And that’s how I got to London. And I had no place to live, and nobody to live with, and no money. And I’m still very fragile and weird.

White: I’m curious to know how you connected with John Lifton. How did you meet him?

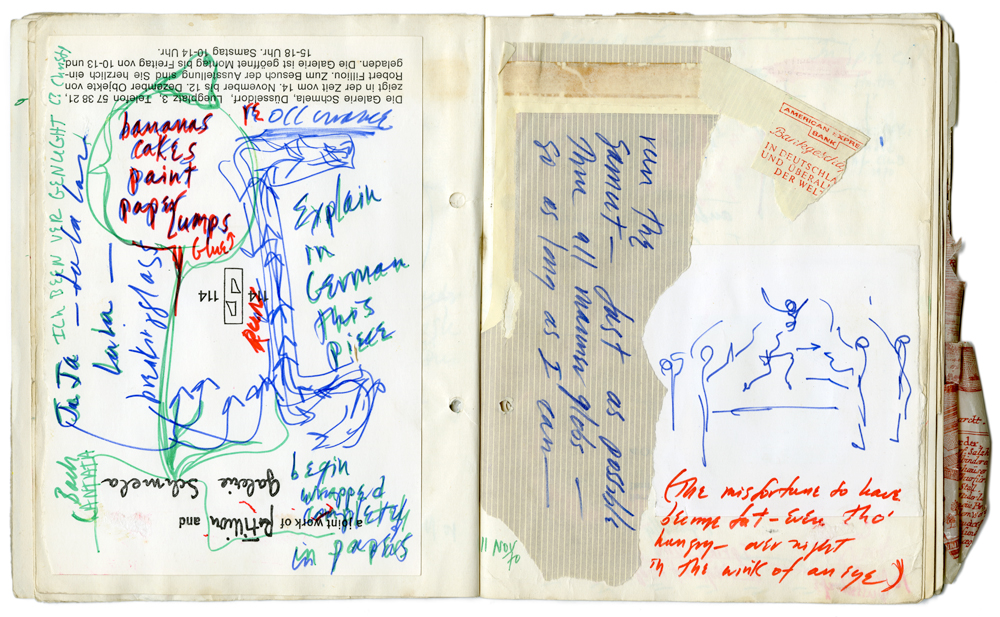

Schneemann: I ended up moving into his tent in the alternative film space [London New Arts Lab]. How did that all happen? We definitely had a love affair, and it was based on work, ideas, and then I ended up moving into his tent in the alternative film space. It was really cold, with no heat, only cold running water. I think it had been part of a dairy. A lot of artists were living in that alternative space and we all had incredible plans for media and thinking about media, and we were making film already. Most of us belonged to the film co-op [London Film-Makers’ Co-op]. John was very interested in different aspects of performance, in singing, he had a beautiful voice, and was a kind of media genius. So I guess when the invitation came from Cologne, I went right to him and said, do you want to work on this? This could be amazing. And he did. And he was very focused and willing and we thought about what kind of system could have simultaneity of images and motion. So we were on a search to design something that would accommodate these potentialities. And then he said we need a computer. That seemed hopeless because in those days they were hugely expensive and rather rare, but he found one behind a grocery store, and he was smart enough to figure out how to reprogram it.

White: He seems to have been everywhere at that time.

Schneemann: Everything he did was so far-seeing. And he was just one of the nicest people you’d ever met. You know he had me washing his socks when [we] lived in the museum? And he had a wonderful wife before he died, who was a cat person. He heard about my work, and I, of course, was very skeptical. I couldn’t believe anybody quite respected it enough to do anything for it. But here was this opportunity and we went for it. And together, John and I did a budget, and all the units and parameters of the installation, the intention, and then, of course, the problem was that we were sent the money for production, but Harald didn’t save any money for our hotel and food once we got there. And we had no money at all. We were counting on a per diem, absolutely counting on it. So other artists had to feed us, actually, and give us money to take a tram. But there was one woman there who decided she wanted to take care of us, and that was a patron named Mary Kaplan. An amazing wonderful helper. They said, someone just gave us enough money for you to get a hotel and restaurant meals for a week, and we said, really? How could that be? And the other artist or whoever it was who knew said, it’s an anonymous contribution. And finally, we found out it was Mary.

White: Nice.

Schneemann: That was wonderful.

White: I remember you describing Thames Crawling (1970) as also a part of the Meat System series (1970–71). Can you tell me more about Thames Crawling?

Schneemann: Those were based on inflatables, on finding the right sort of blowers, air machines that could inflate a huge plastic rectangle that could fill the audience area and force them out. So I had a whole team that was blowing, they had the blowing machines on the sides, and then we had to have a crew that would help this huge inflatable move through the auditorium, pushing it forward so that the people would realize that they had to run away from it.

White: Run away from the work.

Schneemann: Yeah.

White: That’s a great joke on them, on the kind of reception and antagonism that you were receiving.

Schneemann: After being naked, and then all that pernicious excitement, all that vicarious excitement. They deserved to be excluded, so they became the waste product.

White: That’s really funny.

Schneemann: It was great fun for us, and it had a good ferocity to it. They couldn’t really get hurt, but they had to be removed. Were we still naked when we were pushing the inflatable? That I don’t remember.

White: I think you wrote in More Than Meat Joy (1979) that there were these really aggressive men in the audience who ripped your clothes away from you, that as the inflatable was enlarging, there were these guys who suddenly pulled clothes off the performers.

Schneemann: Ah, then we had gotten dressed. It was a useless attempt to normalize.

White: How did you come to the term “Meat Systems”?

Schneemann: It’s easy, you know, it was a system, a computer system, that was based on Meat Joy (1964). We liked that. We were feeling really meaty ourselves. I built the installation Meat Systems, with the computer-driven projection systems, the one that was presented in Cologne, with John.

White: Yes I’m curious to hear more about that. I’ve seen the documentation in More Than Meat Joy.

Schneemann: It’s not good documentation. That was a very complex, sophisticated work. John found a computer thrown out behind a grocery store. I had always wanted to do a multiple projection system of images moving 360 degrees in space, and I wanted to see if I could maneuver slides of Meat Joy, Water Light/Water Needle (1966), and Snows. Had I already built a mirror system for something? When’s my first mirror system?

White: Hmm…

Schneemann: Well anyway. We bought a mirror system. I have it. It’s called a diaphragm. It’s a little cloth with hundreds of mirrors on it. And John found that. And he found the computer. And I designed the slide sequence, and we made the computer accept three—I haven’t talked about this for a hundred years—three layers or three stacks of slide carousels with 80 images in each. And he made a program for the computer so that 80 would go around the room at once, through the mirrors, then merging with the second carousel set, and then the third set. So it was beautiful. It was continuous. It was an environment—the images were large, sort of floor to ceiling, and they incorporated the mattress and the bed where we had to live, because we had no money for the hotel. And we carried this computer and the hundreds of slides in a little van, which was taken apart by German customs. They took everything apart. They needed to handle all of the slides, looking for porno I guess. That was an ordeal. I don’t remember how we got it all back, in fact, but it was a wonderful work. It was very very difficult and engrossing, how to contrive the system. And we did, it was great.

White: Do you have much documentation here?

Schneemann: No, no. White: What happened to it? Schneemann: It was the least documented of almost any of my works. I mean there might be something somewhere. I was in with the big guys. And so I thought we had made a truly major achievement. There was Vostell, and Kaprow, and Filliou, all the major Happenings figures were in this museum exhibit. So one morning we were sitting around the lunch table, where I was hoping somebody would buy us lunch, and each guy left the table for a little while and went off in one of the adjacent rooms, and came back smiling. It was like some porno joke. And then the next one went, came back, smiling. Kaprow went first. And then Vostell. And then finally Al Hanson went. And I said, what is it if Al is going? I should certainly go too. And I said, Al, what is it? And he said, well we’ve just all signed contracts with the publisher, concerning this exhibit and our work. And I said, oh shit, no one talked to me! And he said, well I think I’m the last one they talked to. So it’s the same old thing. The same old crap. They were all getting intensive documentation for the book project that was underway. And whatever I could put together, John and I had to shoot it ourselves, and we were too busy, or too hungry or something.

White: Wow. I’m sorry. What year was this?

Schneemann: Happenings & Fluxus in Cologne, 1970.

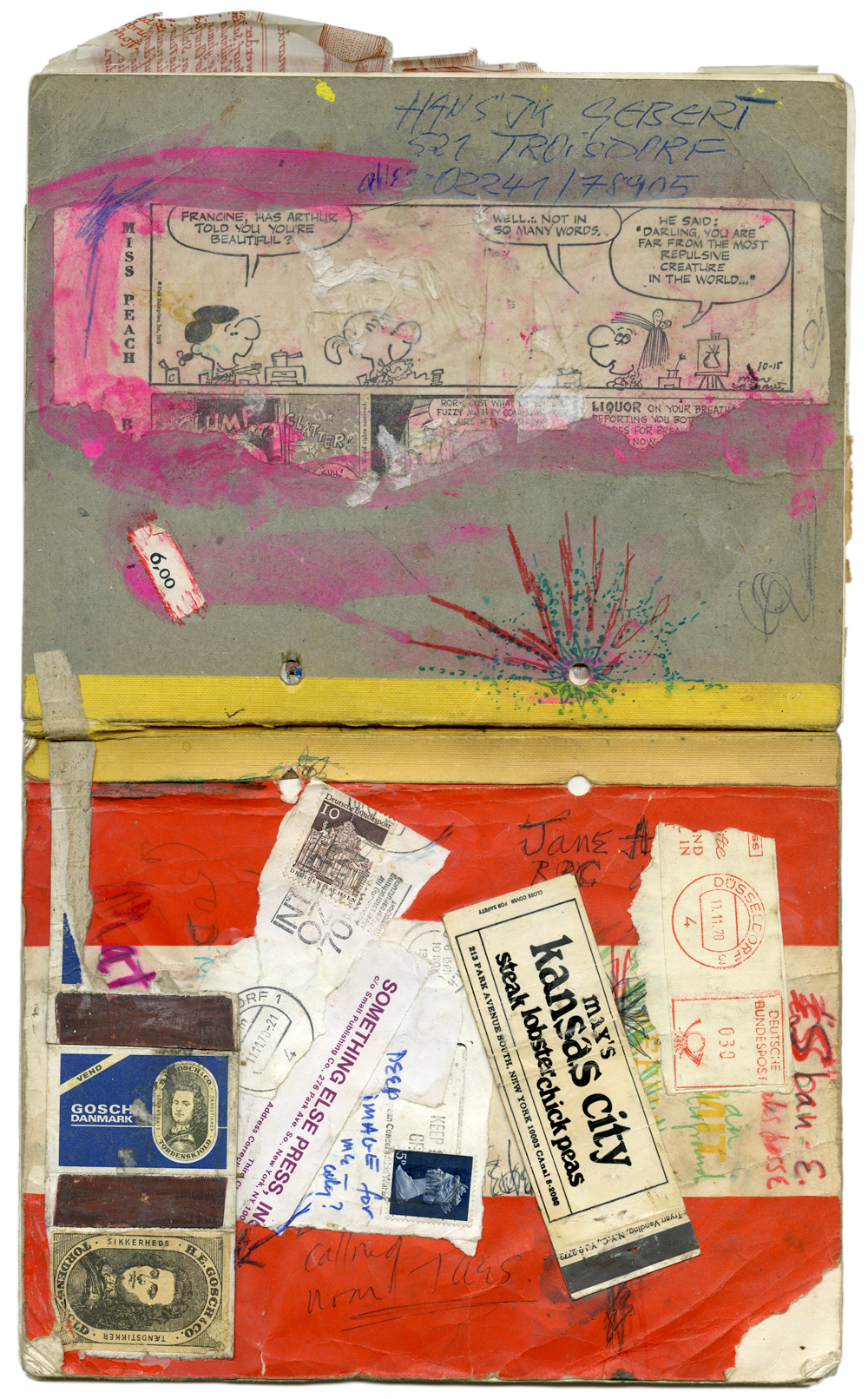

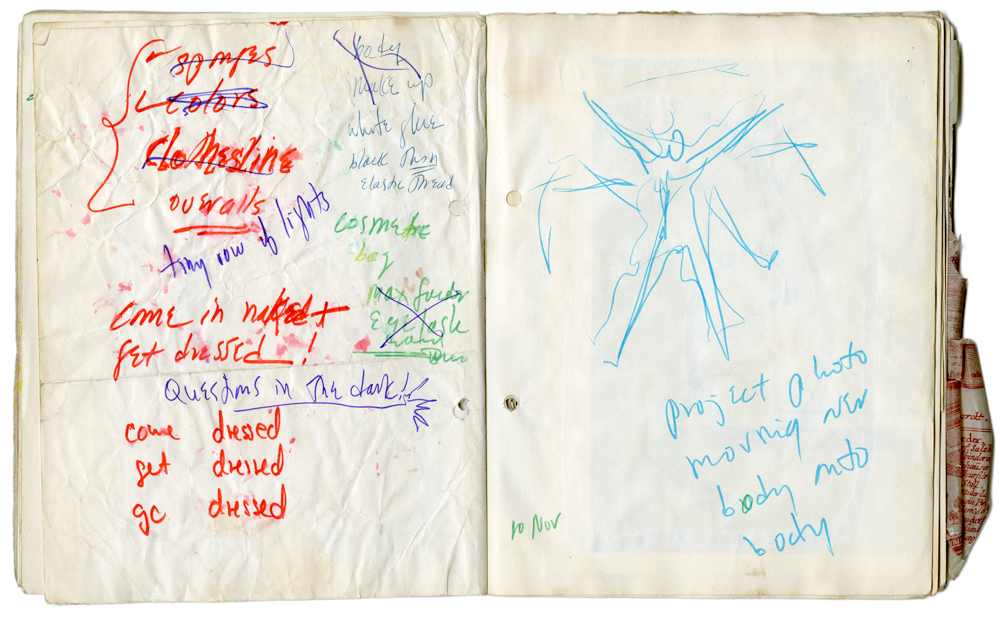

White: You said you kept diaries of this time as well?

Schneemann: Yeah all the time, but most of them are just about sex. I don’t know if it’s anything very interesting. That’s why I think you’re not supposed to look at it until I’m dead. Save the embarrassment of the people who aren’t dead, or giving other people grandiose ideas.