Christina Wiles

CHRISTINA WILES: I’m interested in your project Frontera/Territorio (Border/Territory). For that project, you conducted audio interviews with people who live near the border of Colombia and Ecuador in your home region of Nariño, Colombia. You asked them about their associations with the words “border” (frontera) and “territory” (territorio). Based on those interviews, you produced sculptures and an installation. Could you talk about the project, how it began and what the outcome was?

SAMUEL LASSO: I was interested at first to see that there is a history of political conflict between the two countries, but as I progressed through the project, I became more interested in the personal experiences of the inhabitants living near the border. I think the experiences and perspectives of the people is what matters. After thinking about this, I had the idea to interview people as a way to access the deep sentiments arising from those who inhabit the area. The interviews were the cornerstone of the project, and it was from the interviews that I got the inspiration for the sculptures.

With a research-based project like this, how did you decide what physical form the project would take?

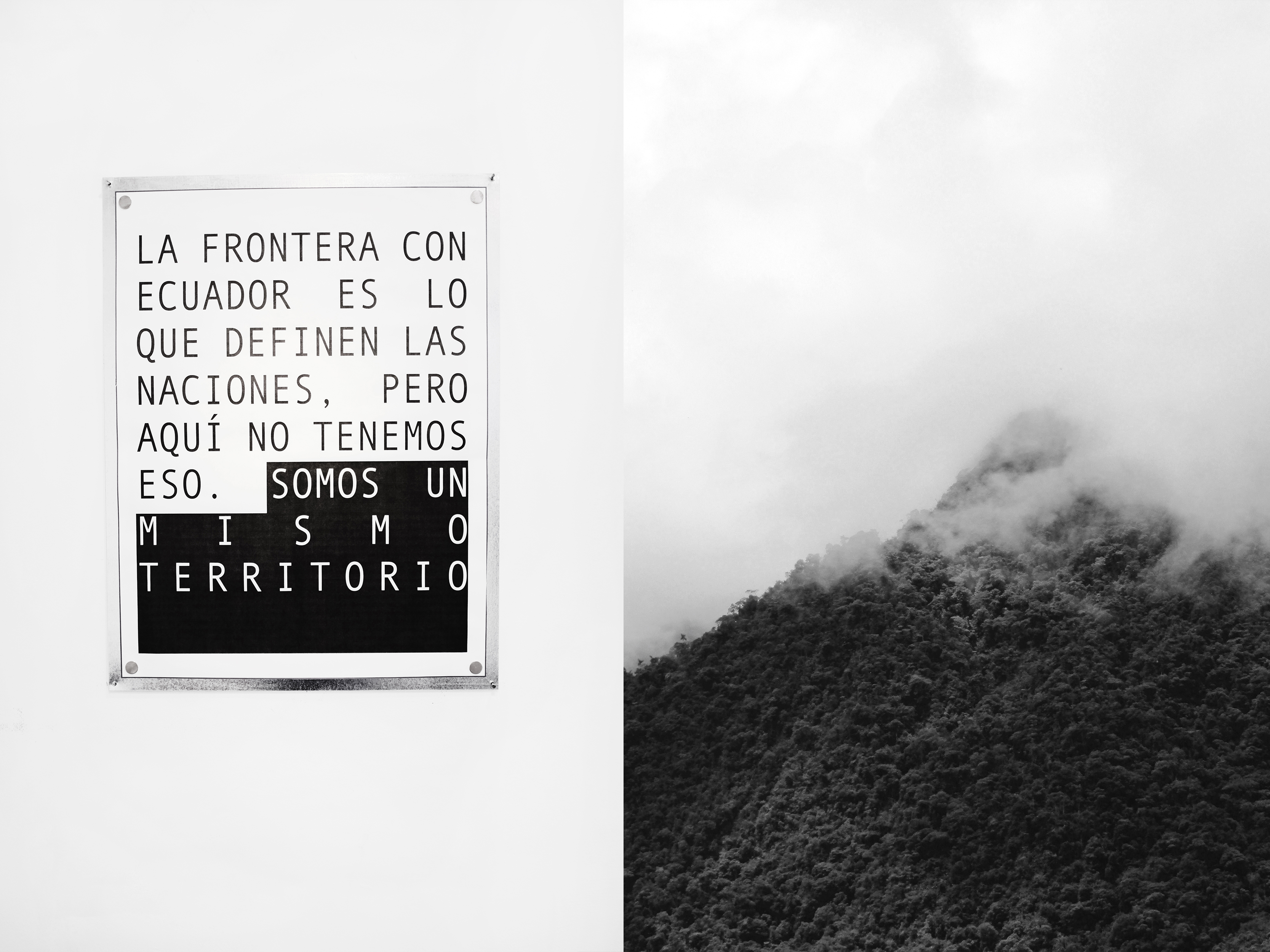

At first I wanted to include the full interviews in the exhibition, but the idea of including phrases or keywords interested me more because a phrase can have greater impact on the viewer. Ultimately I selected six quotes from different people to include in the exhibition.

The border between Colombia and Ecuador is inhabited by an indigenous community of Pastos who live in the areas around the Chiles and Cerro Negro volcanoes, which is perhaps why the volcanoes were mentioned in most of the interviews. It seemed significant to me that the volcanoes were mentioned in most of the interviews. The volcanoes are such a presence. They teach people how to live in coexistence with the land.

Why did you choose the border between Colombia and Ecuador? Do you have personal associations with this border?

I am from Pasto, a Colombian city very close to the border of Ecuador, which is why I’ve traveled so often to Ecuador with my family. The idea of working in this area was actually something I thought about as a child. I always perceived a hostile relationship between the two cultures and I thought it was strange because as a child I could not see any difference, only similarities, and I still see similarities.

How did you find people to talk to and interview? And what questions did you ask them? Did you ask them all the same questions?

I owe everything to my sister. She helped me find people to interview because she is very social and has spent a lot of time in the region. The questions were the same for everyone and very simple. I just asked: For you, what do frontera and territorio signify?

In the United States, there is a huge amount of political rhetoric right now related to the border between the United States and Mexico. President Trump says he wants to build a wall along the border, and the topic has become divisive. In 2018, the United States Federal government shutdown over a disagreement about funding for the border wall. Is the border between Colombia and Ecuador politicized?

The problem between Colombia and Ecuador has many shades and one of those is certainly political. There have often been tensions, and one of the most difficult issues is the presence of guerrillas and drug trafficking. This affects the border and it seems that the governments only seek out further division.

I’m interested in the linguistic aspect of this project. By choosing to focus on two specific words, two linguistic utterances, frontera and territorio, you highlight the role of language in the construction of borders. Could you share your thoughts about the relationship between language and the maintenance and construction of borders?

At the time of the interviews I thought of these two words. I was also thinking about the word límite (limit), however I ultimately decided to go with frontera and territorio. For me, border and frontier mean the end of a territory, and a territory represents a political construction with which each country governs the land, and that is what generates the frontier or the border.

The word frontera does not infer a limit that we cannot cross—the frontier can be seen as the end of something and the beginning of something as well. Countries are in charge of limiting the territories that they govern; in the mountains between Ecuador and Colombia, its inhabitants do not have the vision of a frontier or border as a limit, since they are not governed by these laws.

This work is research based, and by that I mean you began the project by collecting information, then you created sculptural objects based on your research. Your research seems related to the kind of field studies an archeologist or anthropologist conducts. Do you see it that way? Have you always been interested in this kind of research-based process?

Yes, collecting data or material is a constant in all my projects. Sometimes I collect only raw materials like rocks, branches, etc., or for other projects I’ve compiled various forms of information such as interviews. I think this process came from the insecurity of being unable to cover the issues I was interested in. Instead, I tried to collect whatever else I could, and then I began to see this as a strength of the work and a new way of working. I’ve always liked sociology and anthropology; my three older sisters all study issues related to those fields.

Was there anything unexpected or surprising as you were making Frontera/Territorio (Border/Territory)?

I was surprised to see how all respondents who I interviewed connected the word border to a government construction, one that does not represent the experiences of the people, while they related the word territory to land and nature. It was something I did not expect and I found it fascinating.

I’d love to hear about one of your other works, La tierra es más que una línea donde empieza el cielo (The earth is more than a line where the sky begins). Could you describe the project?

This project was born from another project for which I traveled all through my native region (Nariño), through all its municipalities (villages). On these trips, which took me more than three years and a lot of money, I saw a lot of abandoned, destroyed houses; in several cases I also saw firearms. Some houses were already reduced to just their walls, traces of homes that are now reclaimed by nature. Those encounters struck me, and I decided to work through the idea as a separate project, which became La tierra es más que una línea donde empieza el cielo. These abandoned houses are actually the result of violence and war in my region Nariño. The violence has led to large displacements and a decrease in rural populations in certain areas. The abandoned house is the symbol of a place that is no longer and is lost. It is

an image of rootlessness that evokes the suffering experienced in this region. So I decided to create and install a desolate landscape filled with fragments of destroyed walls.

Do you consider your sculptures a kind of abstract cartography?

Yes, totally. Initially I intended the sculpture 64 (2017) to take the form of a map, but the result was too literal for my taste. The final form of the sculpture included bags of dirt from each province of Nariño. I like to think that each object, each individual piece of that sculpture is itself a source of information. Each sample of earth was collected from a specific location in Nariño and that meant that I had to travel to each place, meet people there, and learn about the customs and difficulties of its inhabitants. So the sculptures are also a map, if somewhat absurd.

Your work leads me to consider the idea of ruins, both their form and their cultural function. When I think of ruins, I think of something consumed by time; I think of the absence of a whole, and sometimes something intended to memorialize, honor, and stand in for what no longer exists. Your sculptures are not actual fragments of the houses you encountered in the Nariño countryside—you constructed them to stand in for the fragments of the houses you saw—but do you still consider your sculptures to be a kind of ruin?

My idea was to make a somewhat gloomy and desolate landscape. Many viewers saw it as a post-apocalyptic city, so the idea of ruin was always present.

There is an act of making visible what has been lost. There seems to be a sense of grief in that, though I’m wondering whether you see it that way? Do you feel a sense of loss or grief in this work?

I had never traveled as extensively throughout my region, so it was nice to have that opportunity, but it was also a very difficult experience. I was accustomed to living in the city center (in Pasto, the capital of Nariño), but in the areas outside the city people live in totally different conditions. Neglect by the state has generated many problems. I wanted that experience to be embodied in the work, both the good and the bad.

In La tierra es más que una línea…, there is an ambiguity between the organic/natural and the constructed/man-made. The sculptures are made of soil and seem to be of the earth, yet you painted them to look like remnants of the wall of a house. Is this an important aspect of the work, for you, the ambiguity between the natural and the man made?

In general, there is a cross between what is man made and what is natural in my work. In this project, “the ruin” contained the natural and the artificial in a single object, which I totally appreciated. Some of the houses I encountered in the countryside on my research trips were difficult to recognize—they looked like plants or small mounds of earth. Nature reclaims these structures quickly.

In the various sculptures that are part of the series La tierra es más que una línea…, you integrated physical pieces or traces of the places you visited in Nariño. You collected samples of earth in each province and used those pigments to produce paint for the sculptures. Was it important to you to be able to integrate a physical trace of Nariño into your work? Do you think it would have changed the impact of the work if you had used paint that you bought at the store?

Emotionally and symbolically I think the pigment extracted from the land is second to none. I am very romantic with materials and I like the idea of bringing the viewer a real footprint: it is perhaps the clearest manifestation of archeology in my work.

I’m also interested in your earlier work, A un volcán no quieres verlo directamente a los ojos (You don’t want to look a volcano straight in the eyes). Also a research-based work, it is a sculptural interpretation of what it would look like if the Galeras Volcano exploded, and the sculpture is accompanied by found photographs from the Colombian Geological Service, right? Could you describe the different components of this work?

Yes, the exhibition of this work included the sculpture that referenced the volcanic eruption, and the sculpture was accompanied by an artist book containing archival photographs from the Colombian Geological Service. I also included the preliminary sketches I made for the main sculpture; these small sculptures are different from the main sculpture because they are actually studies of different coal-derived materials. I was looking for a texture similar to that of dry lava.

From what I understand, you began this work, A un volcán no quieres verlo directamente a los ojos…, by exploring field studies produced by various institutions and universities in Colombia around the time the Galeras Volcano erupted. The field studies included interviews with the people living in the areas surrounding the volcano. Could you describe your process for making this work?

My research time for this project was one year. I wanted to work with concepts like roots and also the volcano as both protector and destroyer. The people have a different understanding of the Galeras Volcano, totally opposed to that of scientists studying volcanic activity. I remember a text that said that the eruption of the Galeras Volcano could generate a tragedy and bury all the nearby inhabitants. That text gave me the idea to create a sculpture of the material aftermath of an exploding volcano. In Armero, Colombia, a real tragedy happened that was very similar to what the text described.

Do you see a thematic relationship between this work and the other works we’ve discussed in this conversation?

I think they are all the result of tensions inherent to the human-nature relationship. Although they take up different themes, their focus is the same: how we relate to our environment. A border is a space—a landscape that is inhabited by society—and government policies complicate that relationship. In A un volcán no quieres…, the relationship between the volcano and the people who live in the evacuation zone is a kind of intimate and ancestral relationship; while in La tierra es más que una línea…, the relationship is about the political violence in the region.

Could you talk about your interest in land and the natural landscape? When you were a child, did you spend much time in nature?

As a child I remember long river trips with my family. We took pots and we cooked in nature. I remember helping my grandfather gather coffee in the village, which was something I enjoyed very much. Nature was always present and still remains in my life. Where I live in Pasto, it’s normal to go for a walk to a waterfall. If you look out the window of my room, I have a view of a mountain.

What are you working on now?

My current project addresses mining. I’m interested in the idea of extraction—extracting objects of value from nature and the problems this entails. I’m currently collecting stones with gold taken from different mining operations in Nariño. As always, at the start of each project I have no idea what the physical result will be, so I find myself still in the process of collection.