Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin

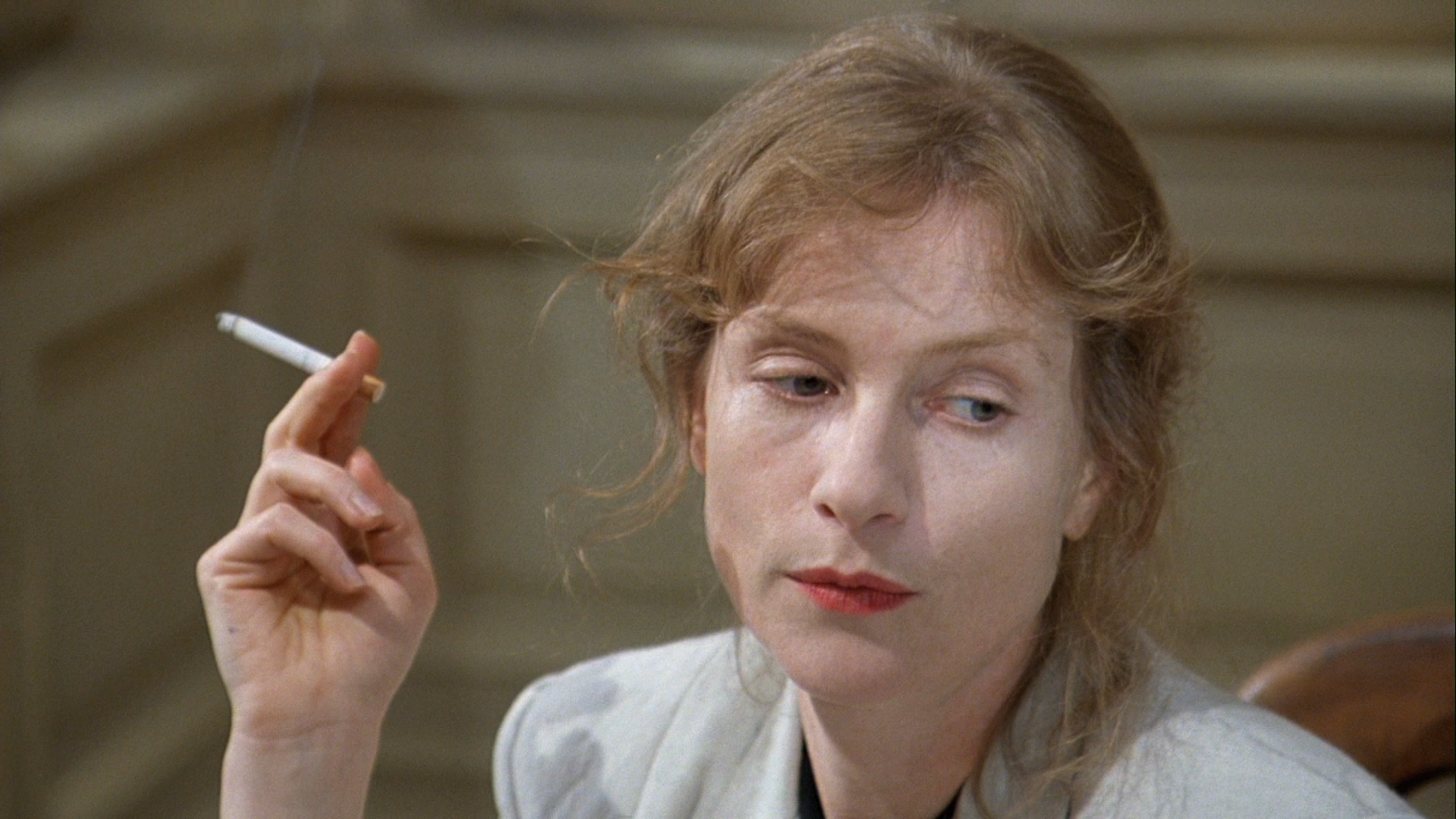

Isabelle Huppert, on screen, has a very particular smile. It rarely has anything to do with opening her mouth, showing her teeth, and bellowing a laugh. It is simply the movement — sometimes just a twitch — of her lips, straightening them out to signify a slight smile. As she gets older, these smiling lips form a wide, tight line across her face, almost as if drawn there.

There is a curious vacillation in the way we are tempted, as spectators, to describe Huppert’s process. Are we watching her at this moment, when she smiles, or the fictive character she is playing? More than with most actors, the border between actor and role seems to evaporate swiftly, if it ever existed for her in the first place. It is almost impossible to distinguish Huppert’s “characterization” from one performance to the next. The same placid reactions, movements, and gestures — such as that flatliner smile — recur in unexpected permutations and combinations, no matter the fictional situation or historical period. And yet we never have the sense that Huppert “plays herself” in the way that many actors do. Huppert’s “self” is more mysterious, fugitive, and hard to get a fix on. The crux of her performing craft is a condition she calls interiority, the dead opposite of actorly exhibitionism. She often appears to be in a state of internal retreat or withdrawal.

Huppert, now 64, is in some respects an odd and unlikely candidate for the level of stardom she has achieved. There is very little that is “feel good” or sentimentally manipulative about her style of acting – her roles are often bleak and perverse (the occasional zany comedy aside), and almost always selected on the basis of the director, rather than the script. From Bertrand Blier’s Going Places (1974) to Patricia Moraz’s The Indians Are Still Far Away (1977), from Jean-Luc Godard’s Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980) to Marco Ferreri’s The Story of Piera (1983), from Michael Haneke’s The Piano Teacher (2001) to Christophe Honoré’s Ma mère (2004), from Claire Denis’ White Material (2009) to Eva Ionesco’s My Little Princess (2011), from Catherine Breillat’s Abuse of Weakness (2013) to Paul Verhoeven’s currently much-acclaimed Elle (2016), Huppert’s roles constitute a veritable gallery of female abjection, whether ending up in tragedy or triumph.

Unlike Julianne Moore, Meryl Streep, or Vanessa Redgrave, Huppert is not an actor who virtuosically alters her appearance, vocal tone, or accent from role to role. At most, she changes costume style or hair color in order to “differentiate the role from oneself,” as she says, given how swiftly she moves from one project to the next. In general, Huppert appears to insist on the complete opposite of traditionally chameleonic acting: she offers herself as a kind of unadorned, blank screen that can reflect and refract whatever surrounds her in any given film. Some directors understand this central, almost Bressonian aspect of Huppert’s artistry, and work with her accordingly. But even her most glacial performances are regularly traversed by a volcanic, hysterical energy that expresses itself in sudden manifestations of emotion. What kind of continuum can be established between these extreme poles in her acting?

Return to the shadow of her smile. It is only one of many gestures that Huppert is fond of producing in an abrupt and beguilingly discontinuous way. If she’s alarmed or besieged, she gives a short, sharp scream. If she’s waiting or thinking or tense, she licks her lips with her tongue. She will often deliver the most innocuous transitional lines (like “ooo la la!”) with unexpected emphasis and “color.” She flutters her hands in “go away” gestures, impulsively massages her neck, clears hair from her eyes, blows air out of her mouth, and vibrates her lips in an exaggerated vision of relief. These various expressions flare up, and then die away almost instantly.

Huppert speaks of her joy in working with “details” such as these, stringing them into a sequence of actions within a shot or scene. Her character, in each role, is the unstable accumulation of such discontinuous signs. In Maurice Pialat’s Loulou (1980), her face is a non-stop parade of inscrutable micro-expressions, wheeling from one end of the emotional spectrum to the other. Stick her next to Gérard Depardieu (as Pialat does) in long-held two-shots, in a bar or in bed, and it’s a carnival of unpredictable affects.

Huppert is sometimes criticized as a cold, cerebral actor. One would not think this reading her interviews. When asked about her craft, she speaks of “pure feeling” and “living in the moment” and says that little is discussed with the director beyond the essential logistics of a scene (where to move, at what pace, etc.). “There is no direction of actors” is among her favorite mottos. Rather, as she explains it, an actor inhabits the film — an entity that is bigger than the conscious work of cast and crew combined — and rides along with it, feeling its vibrations, sensing its needs from moment to moment.

This is not about being absorbed into the imaginary world created by the film, in the way that Willem Dafoe, for instance, describes his immersion into a role. For Huppert, ever-conscious of the camera and the surrounding mise en scène, it is more a matter of responding to a certain regard defined by that camera, and to the particular mood, viewpoint, and purpose of the film-project — even when these aspects are not verbally articulated by the director or writer or anyone else involved.

The film and theater director Werner Schroeter (1945-2010), who included Huppert in half a dozen of his projects, praised her as an actor who does not need “psychological humbug” explanations, and does not perform in a psychological manner: she appreciated (much to his taste) that acting is, above all, work — physical work that demands an intense concentration of energy. In his remarkable 1990 film Malina, for instance, Huppert willingly spent long hours on the set amidst real flames. Huppert herself echoes this when she speaks of generally preferring to play a “series of poses,” rather than a conventionally three-dimensional character.

These accounts do not always tally with our experience of the films that result from such creative processes. Isn’t Elle, for instance, an especially complex exploration of a particular woman’s very unique psychology and experience? Yet, even in this case, Huppert’s own take is intriguing. While claiming that she and Verhoeven did not much discuss her prior roles for Claude Chabrol in films including Story of Women (1988), Madame Bovary (1991) and Comedy of Power (2006), she notes something particularly “Chabrolian” about the main character in Elle: “Her past is a hypothesis; others around her run about offering exact explanations for her behavior. That’s how Chabrol worked, too: he gave us social hypotheses, a family hypothesis, a professional hypothesis — to the point where we don’t grasp at all what makes up this character.” As frequently with Huppert’s roles, this one in Elle is “difficult to reduce.”

Looking at a group of films connected by the thread of an actor who is common to all of them brings a different, refreshing slant to the “auteurist” analysis of cinema. This is not to say that an actor, even one with such star power as Huppert, sets the principal, artistic intention of a film over and above the director (although it is a well-documented fact that producer-actors such as Tom Cruise have enormous control over the final product, and Huppert herself initiated the White Material project with Claire Denis). But we can grasp a different “constellation” of meanings and emotions across a diversity of films if we agree to experimentally treat the main actor as also the main auteur. This is especially so when we consider the passage of years and decades: in Huppert’s case, metamorphosing from rebellious daughter roles in the 1970s to ambiguously amoral mothers today. (Elle, with its four generations of a family, is fascinating in this regard, and Verhoeven — unlike most filmmakers — does not cheat in his age-casting: Judith Magre, playing Huppert’s mother, is 90!)

There is one aspect of Huppert’s progression, in this regard, that is particularly striking. Huppert has always looked younger than her biological age, and she has taken advantage of this fact in the practical way that any lucky actor would. In the 1970s, she was still able to play teenagers while already in her mid 20s, and in the 1980s could easily incarnate a character at the different decades of a “historic chronicle” like Coup de foudre (1983). But at the same time, Huppert uses this ambiguity to explore a rich range of uncanny, sometimes disquieting effects. As the postal worker in Chabrol’s The Ceremony (1995), she projects girlishness even when she is killing people with a shotgun; and in My Little Princess, where she plays a lightly fictionalized version of the controversial art-photographer Irina Ionesco, Huppert’s lack of conventionally maternal attributes makes her seem like a sister or friend to the character of the young daughter.

Still, if there is an evolutionary arc that survives such indeterminacy and age-shifting in Huppert’s career to date, it is this: from often playing the melancholic, alienated or sullen outsider in her early, youthful roles, she eventually traversed the various social barriers to be installed as the “perfect bourgeois” character. Examples of the former type include the sad love story The Lacemaker (1977), and Chabrol’s recreation of Violette Nozière (1978), a teenage “free spirit” of the 1930s who murdered her father; while the latter type is embodied in Chabrol’s later films, François Ozon’s 8 Women (2002), The Piano Teacher, and many others. This makes for a fascinating comparison between eras, and between types of cinematic stories. In her roles for Godard in Sauve qui peut and Passion (1982), for example, Huppert is the struggling worker-girl: enduring routine sexual humiliations as a prostitute in the former, literally stuttering to make her point to her lover-boss in the latter. Lacking any external power, her characters of this period need to withdraw in order to carve out for themselves some private space for reflecting, dreaming, desiring. As certified members of the bourgeoisie, however, her later incarnations become masters of often sinister control through subtle manipulation and stage-managing.

This returns us to the interiority so characteristic of Huppert’s art as an actor. She has often described the task of acting as the quest to find an “interior space” within the general frame of the surrounding mise en scène, whether theatrical or cinematic. Through this process, she seeks to give her characters not only a buffer of privacy but also a vast zone of secrecy, of enigma. These secrets can be dreamy (as they were for the younger Huppert roles), or malicious (in her high bourgeois mode), or both at once. Hence the perversity factor very often at play in her performances: this interior escape, a necessary flight from harsh reality, gets somehow twisted up behind her inscrutable façade, and relaunches itself in strategies, schemes, or impulsive acts of either other-directed aggression or self-mutilation, such as we see in Malina or The Piano Teacher.

Recently, Huppert was asked about her ability to produce such wrenching tears on screen. She almost shrugs off the question: “We all have a deep well of sadness and despair in us. It’s not that hard to find.” The interviewer persists: but how, technically, can you make yourself cry? “I can do it at any moment. It’s not complicated. If you ask a pianist to play a Chopin sonata, he plays it. If you ask a dancer to produce a step, she does it. There’s no masochism involved; it’s pure pleasure.” Then she gives the reflection a philosophical spin: “There’s no suffering in this suffering … To act is a necessity; and it’s easy for me to do. I’m not one of those who complain that a particular role was ‘difficult’ … I stick with a certain nonchalance, which can border at times on indifference.” All the strangeness and uniqueness of Huppert’s acting is captured in this testimony: whether she appears blank, or enters into a state of hysteria, she reserves the innermost part of the process for herself, as her secret. At her interior, apart from the world, apart from society, she is free. She is weighed down by nothing, which is why she can declare: “I value lightness above all else.”

All quotations from Huppert are translated by us from interviews in two issues of Cahiers du cinéma: the special “Autoportrait(s)” issue that she guest-edited in March 1994 (no. 477); and Stéphane Delorme’s “Jouer,” recorded in Cannes for no. 723 (June 2016). Below: an audiovisual essay by Cristina Álvarez López & Adrian Martin: “I Furrow My Own Film Inside Those I Pass Through”: Isabelle Huppert, 2017