Interviewed by Alex Kitnick

Alex Kitnick: I was wondering if we could begin by discussing the different contexts in which you’ve placed your sculptures. With The Street (1960), for example, there were both performance and gallery incarnations of the project that shared similar objects but which treated them very differently.

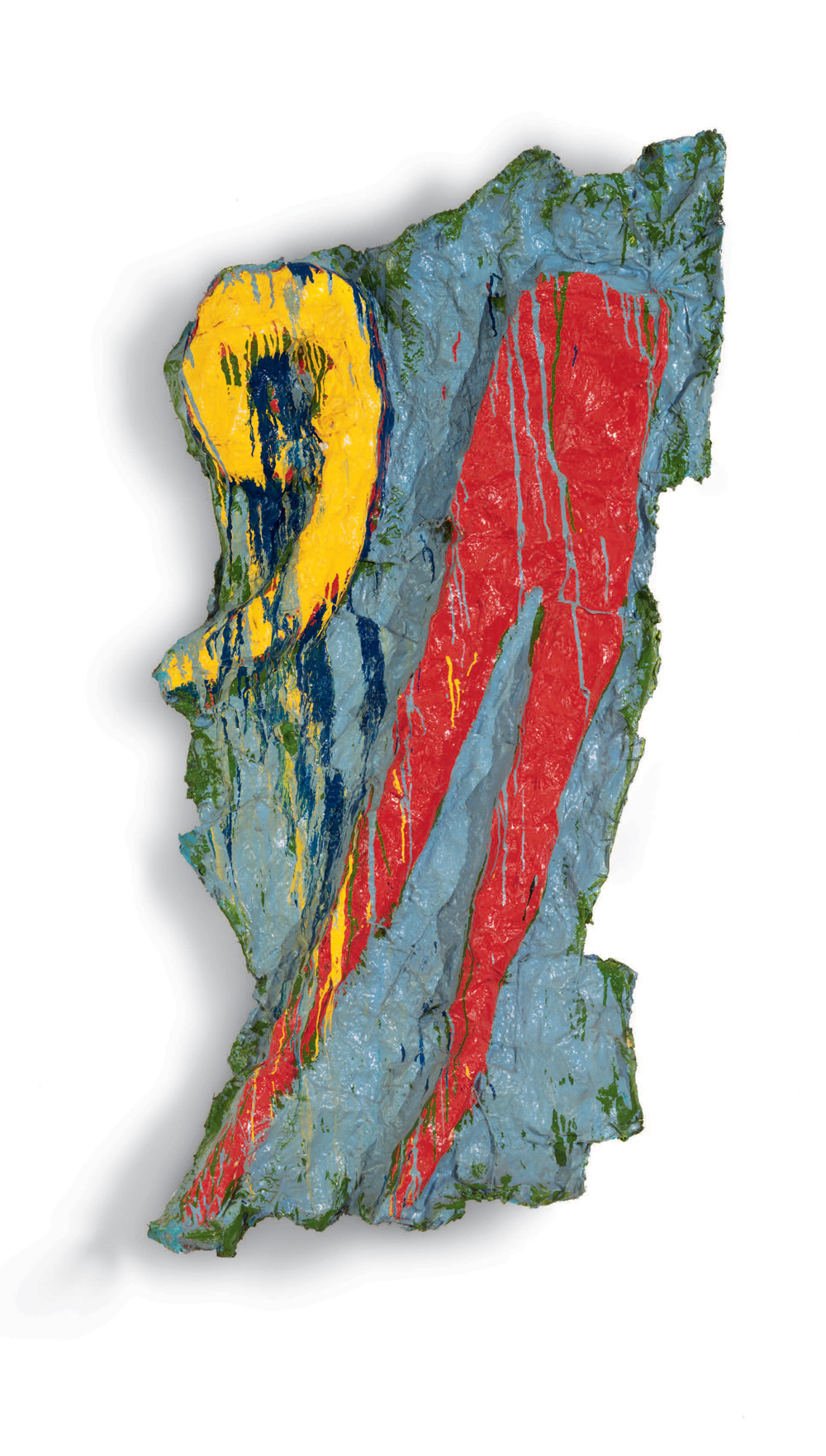

Claes Oldenburg: Well, the group called The Street are objects that relate to the street and people on the streets. The Store (1961) shifts it to what’s beside the street, say. It’s like when you’re looking down on the sidewalk and then you turn your eyes up and you see the stores. So that was another group of things. The Street was really grey and black and brown, and The Store is very colorful. They’re quite different.

Kitnick: I was thinking of the two incarnations of The Street, the one at Judson Church and then the one at the Reuben Gallery. Did they have any objects in common?

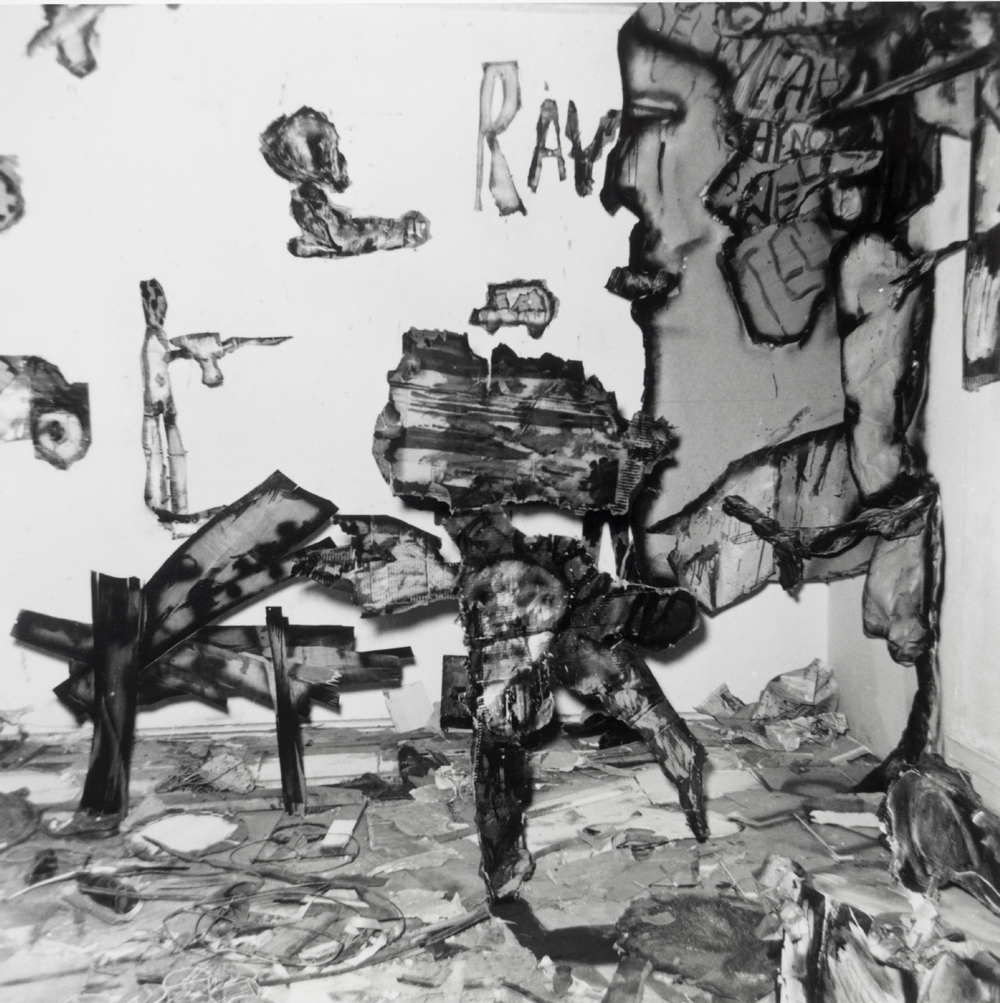

Oldenburg: The one at the Reuben Gallery was more like an art exhibit. It was a new group, because the ones in the first show at Judson were really, as you say, part of a performance. They were tacked to the wall and they were ripped off the wall and taken away, except for a few. Then I continued in that vein and did several others and that was for the Reuben show.

Kitnick: It is striking when looking at this material how much performance you were doing during the sixties, and how key that was to your practice.

Oldenburg: Well all the work is, I guess you could say, somewhat theatrical, which fit it into the way things were going. That, of course, was not represented so much in the show [“Claes Oldenburg: The Sixties”] as it might have been, but there were several films of the performances.

Kitnick: How do you imagine your performances exist today? In the notes? The films?

Oldenburg: You could approach them in the notes, but that doesn’t tell you everything. Some of them have better notes than others, of course. For some of them there was the time to make notes. But I think you really have to see them, I mean I think you really have to have seen them, because they’re not coming back, to get the feeling of them. I don’t think they can be reduced to words.

Kitnick: I noticed that a number of the films are actually authored by other people. Snapshots from the City (1960) was made by Stan VanDerBeek, for instance.

Oldenburg: That’s what happened. I didn’t do the filming, so there was Raymond Saroff, who came in and worked with us during rehearsals, and made films. Stan VanDerBeek made a film which departs from the way I saw it, but that was okay with me. I didn’t want to interfere with the filmmakers. But it does leave out a lot of things, like the use of time, and darkness, and silence, and all sorts of things that simply disappeared when they were reduced, let’s say, to 15 minutes. It was really much longer. Time especially was important, and darkness, but of course you couldn’t film anything in darkness. The best sources of images are the stills, the color stills, that Bob McElroy made. He was a very good photographer and he photographed everything, and that’s the best record. Not the films so much as the stills.

Kitnick: In reading through your writings, and especially some of the writings from The Store, I notice that you talk a lot about the status of objects, which you describe with words like “magic” or the “charged object,” and to me that has a certain currency now, these objects that have a power again somehow.

Oldenburg: It would be interesting if that were true, if what we are talking about here had an influence so long after. But the art scene, it’s so complicated now. You could probably get anything you want out of it. Fifty years ago there were very few artists, and the way they worked was sort of segregated as a certain type of art from another type of art, and so on. People spoke about Abstract Expressionist art, they always had a name—artists, of course, didn’t like that name, but that is what it was called, Abstract Expressionism—and then, when people got tired of that, there were other things lurking in the background, such as collage, and also this sort of thing that I got involved with which was the use of material around you to make art. This was also happening in Europe, it was called the New Realism in Europe, and here eventually it was called Pop art. So then that took the place in the fore-front, and so on. But it doesn’t work that way anymore. Now just about everything is on the forefront. You take your pick. And there’s also so much written about it and so much information you can get on all these things that you can do almost anything at this point.

Kitnick: But it seems like, even then, you were on the margins of a lot of different groups. I was reading this little book that was just republished again called the Waldorf Panels on Sculpture (1965). You seemed to be a little bit of the outlier or outsider of that group, especially in terms of color… the early work, of course, is really papery: cardboard, newspapers, that’s very much the basis of it, it seems. Then there’s a shift in materials around 1964.

Oldenburg: Well the first part with paper, that’s usually cardboard obtained from the street. Also in those days, instead of plastic bags, which hadn’t come in yet, there were sacks made from burlap. In the evening you would go out and see all these burlap bags full of garbage on the street. They all had addresses written on them. I picked up several of those and I used them for works. So the streets were, as always in New York, pretty littered. That was part of The Street, it fit in with The Street since my general approach is to use things that I find in my surroundings. The Store was done in a different way. It was done with plaster on a chicken wire structure, cloth dipped in plaster and laid over it. When they dried, they were painted with hardware store colors. I used only five or six, and I was very careful not to mix them. I had certain rules for using the paint. A lot of them have the effect of some of the abstract expressionist paintings because they have running paint and so on. But I had different reasons for it. I simply wanted to reconstruct the feeling of things as I saw them.

Kitnick: And then after that it was canvas works, and the vinyl works, the soft sculptures…

Oldenburg: Yes, Patty [Mucha]—my first wife—and I were given the Green Gallery on 57th Street to work in in the summer of ‘62, and we were able to make much larger pieces there than we could in The Store, which served as my studio. Patty did the sewing. Together we made these large cakes and ice cream cones and that was the start of another direction, which continued. In ‘63 we moved to Los Angeles and worked in Venice, California where we did a lot of soft pieces. Our theme, inspired by the home furnishings of Los Angeles, became The Home.

Kitnick: I was wondering if in a sense the shift in the material is also maybe a shift in the media that you were interested in? In the beginning, there’s this interest in the street, detritus, the stuff of everyday life, and you’re actually using that to compose the work. And then there seems to be a way in which the media you’re talking about is not quite as directly related. I’m very interested in Marshall McLuhan, and I noticed in your Writing on the Side a number of what seemed like almost McLuhanesque experiments, where you would say: “I’m drowning myself in media, listening to radio all day, three TV’s on,” which sounds like an interest or desire to immerse yourself in a different kind of media environment. I also noticed the performance you did in Stockholm in 1966, Massage, has a relationship to McLuhan, at least in its title.

Kitnick: Oh, I never thought of that. An important thing in that piece was sound, which you don’t see in the photographs. It was a typewriter and the sound of the typewriter was enlarged until it became almost unbearable to hear. The old-fashioned typewriter. At the same time, people were wandering among the audience and giving them frankfurters, hot sausages. Those things don’t show up in the photographs. Sound was very important in all of the performances. And as I say, timing. In the end, it was really so loud you could hardly stand it. You’d put down your hat and frankfurter and put your fingers in your ears.

Kitnick: So were the performances a way of thinking about this other media, which maybe you couldn’t necessarily represent as much in sculptural form?

Oldenburg: Well they were sculptural. They were definitely a balance between objects and sculptures and theater and action. At the end of the performance, all of the objects were usually retired, if there was anything left of them. They might also be remade for the next performance in some other way. I would say the performances were about form and sculpture. They were more related to painting and sculpture than they were to theater. Although I must say, there was a lot of theater, too. There were dramatic scenes, for sure.

Kitnick: Maybe it’s a way of expanding on the sculpture? I mean, is there a sense that sculpture has limits and can’t express everything, and so the performances are ways to draw out certain themes? Or should they be seen as having their own lives?

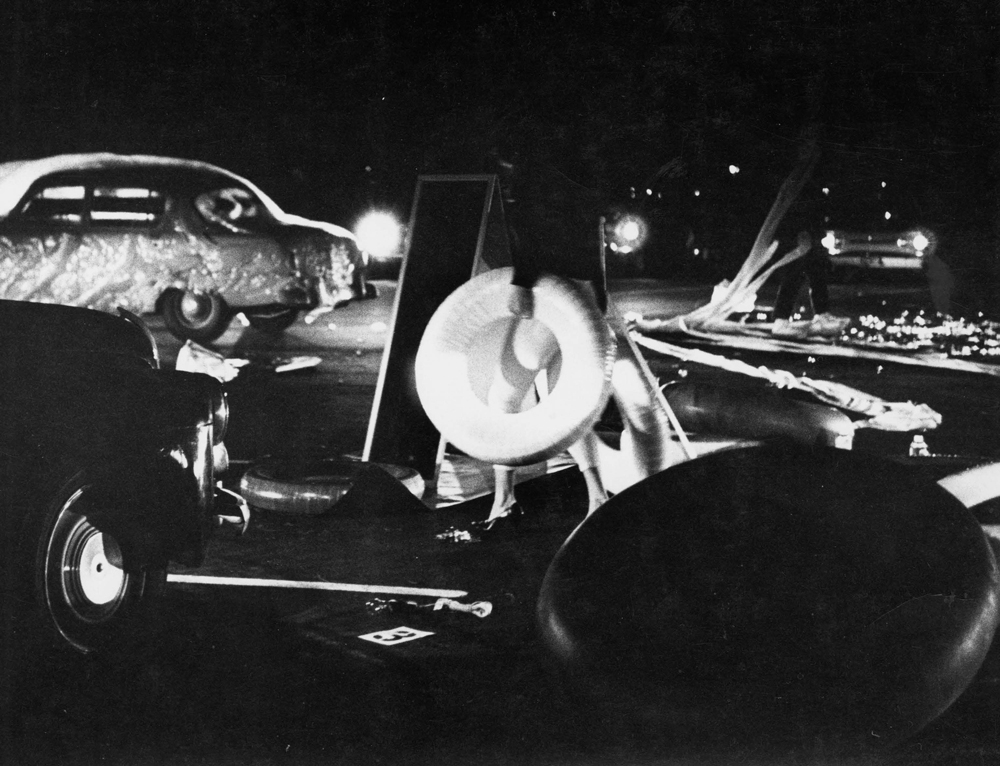

Oldenburg: It all kind of fits together. The things that are going on in the performances are usually like art actions: building something, or collecting something and putting it together in some way. That’s the subject of it. The theater is the place and the timing and all that which surrounds it. There is, for example, the Los Angeles piece, Autobodys (1963), which used automobiles and took place at night. All the lighting was from automobiles. It involved a lot of cubes of ice that were thrown around on the street, which picked up the light. The performances usually don’t have any kind of a narrative, although they tend to end in total confusion. Everyone gets wiped out. That’s the only thing. By the end of the performance, everyone lies still on the ground until people get the hint that it’s over.

Kitnick: That’s a good ending. I was wondering, was there something about LA that made you want to go there in ‘63?

Oldenburg: Oh yes, very much so. I was tired of New York. I had passed through Los Angeles, but I had never lived there. Several people told me that it was really worth going there because it was so different. So we picked up our stuff, Patty and I, and we went there and got a little house on the canal in Venice. And indeed it was different. There was a whole different group of people there that had really never been to New York, artists, I mean, who had their own viewpoint. It was fun to meet them and to get to know them. It was definitely inspiring to go at that moment.

Photo credit: Julian Wasser

Performance at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Photo credit: Ingemar Berling for Dagens Nyheter

Photo credit: Hans Hammarskiöld

Kitnick: Did you meet the people in the Ferus group?

Oldenburg: Of course. And Ed Keinholz, he was a little outside of things, but he was an interesting artist to me also.

Kitnick: Was Ken Price of interest at all? I think of the interest in the object, in sexuality or desire and color somehow…

Oldenburg: Yes, I liked his work, though the scale at that time was rather small. Andy Warhol came out at the same time, so he was on the scene as well. And then we had Dennis Hopper, who was just turning from artist into actor. It was a lively moment.

Kitnick: But you came back to New York, nevertheless.

Oldenburg: We came back to put on a show at the Janis Gallery in April of ‘64. Then we went to another Venice, the real one, because I was in the Biennale. So we picked up our stuff and went to Europe. And we hung around there for awhile because we got to do a show at Ileana Sonnabend’s gallery, in Paris at that time. So we spent August and September in Paris making that show. It was similar to The Store show, except that the type of objects and the materials were more French. They didn’t glisten. I used tempera, which sunk into the plaster, and gave it a Parisian look. Then we came back to New York and got a new loft on 14th Street. The building was unusual. It was all artists. It was one of the first really big buildings to be turned into an artist lofts. Larry Rivers was on the top floor. Patty and I were on the next floor down. And then we had Yayoi Kusama, and eventually John Chamberlain and others.

Kitnick: Sounds like a good group.

Oldenburg: It was a good group. What was interesting about it is that, like this building, it didn’t have much separation between ceiling and floor, so that whatever was going on up there could be heard, if not seen. It was also a very long loft, it was a whole block long, and what we did, Patty and I, we set up places where we would sleep. If they were having a party in the front, we had to sleep in the back. We worked very productively for over four years in the 14th Street space making many large works in vinyl and their counterparts in white canvas we called “ghost” versions. In 1969, the marriage to Patty came to an end. I left the studio to her and moved to North Haven, CT, to be close to a factory, the Lippincott company which was making artworks out of metal.

Kitnick: So did you mostly do gallery shows for the next little while? It seems like you’ve always had a desire, and it became more literal later, to work outside the gallery system somehow.

Oldenburg: Lippincott was focused on art, and that was very inspiring. I switched from soft things to hard things. Lipstick was the first of the large works that I made out of metal, followed by the Geometric Mouse, and that became a whole new direction. In 1976 the Clothespin, a 45-foot high structure, was erected next to the City Hall in Philadelphia.

Kitnick: I passed it the other day. It’s still there.

Oldenburg: That was a real step out, into scale. A big step. And that became the direction from then on. I began to work with Coosje van Bruggen—we married in 1977. All the large scale works were created by both of us after that. We did have, as you mentioned, the point of view that we were going to go directly to the audience, and not go through galleries or museums. We were going to put up a sculpture in the city. And the opportunity for doing this existed at that point. The government was offering incentives by advancing money if a community would match the grant. So this was a great moment for doing that. The city of Philadelphia has a ruling that there should be 1% of the budget of every large building that’s put up that should go to art in some form. They don’t have that in New York. So this was the beginning of a situation where the artist could be free of the gallery or the museum, and could take the money directly from the city or a donor. Our point of view was that we didn’t really want to be a part of galleries. The other thing we insisted on is that the sculptures should be permanent.

Kitnick: Do you make hand-held objects anymore?

Oldenburg: The position we had taken lasted for a while, but we started to give in, in the beginning of the ‘90s. We had a gallery show at the Pace Gallery. And after that we had several gallery shows.

Kitnick: But you did have a long span of not really working in galleries. Ten years or so.

Oldenburg: Yes, but we eventually decided that we could also work in galleries. So it continued to be both after that. But the sculptures were always done outside of the gallery.

Kitnick: Looking back at this moment of the early ‘60s is also a way of looking back at New York, and what it was then, which was quite a different place.

Oldenburg: Well in 1970, New York started to go broke. I wouldn’t have this building if that hadn’t happened. Suddenly, everything cost much less. Artists were buying lofts then. Rauschenberg got his building, and Jasper Johns bought one of the bank buildings over on the East side. Everyone bought a loft because they were incredibly cheap. That lasted for about ten years. Now, of course, it’s a completely different situation. You can’t really get an apartment here, even if you move to Brooklyn. I was very fortunate in the timing. Anyway, New York is always changing. I have been through so many places in New York, so many small studios, working my way up to a point where I got something big enough. So I experienced all of that, and I’ve seen different sides of New York. But there was a rule that I followed, and that was not to go too far or too often north of 14th Street.

Kitnick: That’s a good rule.