Interviewed by Chris Hontos

Chris Hontos: I was wondering if you could begin by bringing me up to date on your projects?

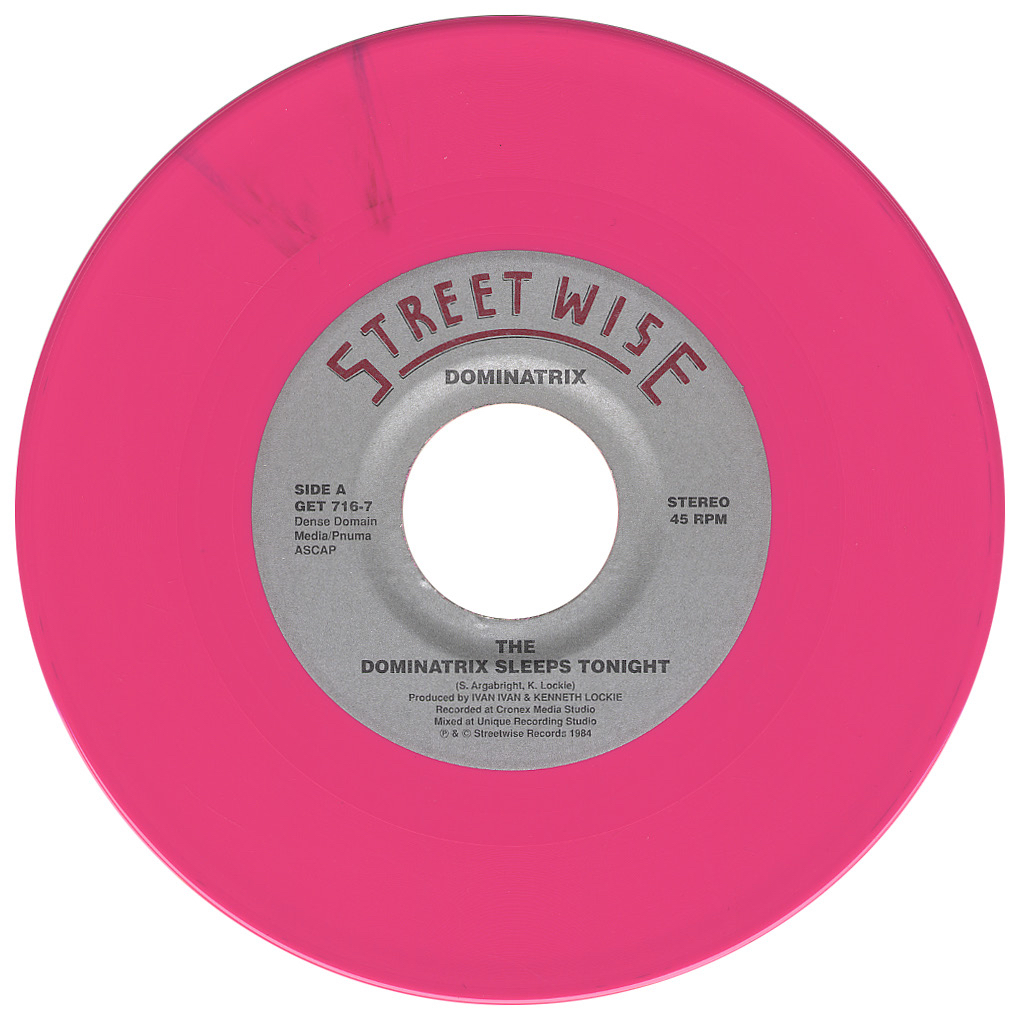

Stuart Argabright: I began forming groups in the late 1970s and continued to do so until the end of the 80s: the Rudements 1977 – 78 / The Futants 1978 – 80 / Ike Yard 1980 – 83 / “Dominatrix Sleeps Tonight” 1984 / Death Comet Crew 1984 – 86 / Black rain 1989 – 98 / The Voodooists 1989 – 92.

All these projects were defining underground electronic / postpunk / club / “riphop” or avant hip-hop / “cybervoudou” and postpunk/hardcore/thrash, especially for critics & writers once they began looking back.

I played drums, did vocals, wrote lyrics, programmed drums, played synths and keyboards, learning as we went along.

That was great fun and a lot of work. Then around 1996 Dominatrix started to get licensed and placed on comps. By 2000, Ike Yard and DCC got into reissue realm; in 2004, DCC was reissued on Troubleman; in 2005, DCC toured internationally and played the Venice Biennale, and by now has more reissues. In 2006, IY reissued on Acute, reformed, recorded a new LP, did some shows and then reissued again in 2012, on Desire (Fr). That’s gone very well, as we went from being known by dozens to having many, many more listeners, and also, generationally, to younger and younger listeners.

I should also mention I was working with Robert Longo & Gretchen Bender in the 1980s and 90s on projects which took us into large-scale art performance involving many collaborators. Then there was scoring for the Rotterdam Philharmonic in 1988, alongside music by Arvo Pärt and Phillip Glass, and I eventually did music for Longo’s Johnny Mnemonic (1995), as well as IBM’s Advanced CG division, and so on. Some of these projects are also being restaged (Gretchen Bender @ The Poor Farm last year).

Point being—all of that has happened and to some extent is still going on, but the bulk of it is in the past. Every group found a home, did a new record or two, and toured. The last one reissued is Black rain’s William Gibson soundtracks from 1994 – 95 on Blackest Ever Black. Black rain is doing a new LP and playing live. So the future is v interesting and dense. Today I am working on developing app software, writing two books (one is based on diaries of club life, 1978 – 89, and the other is science fiction) and thinking about where I want to live next.

Hontos: Given your history of experimentation and your longstanding relation with technologies, it seems like you’re in an interesting position to reflect on the changing paradigms of media, and how new generations of media have impacted the perception of your work.

Argabright: I was born in 1958 so I have seen waves of media sweep over our mind’s eye. I remember seeing the newspaper headline of The Beatles stepping off the plane. Soon it was The Stones doing the same, and then The Sex Pistols stepped off their plane…

I learned a lot by working with different media through the decades—vinyl records, CDs, Laser Discs, and CD Roms. There was 1994’s Innerware, a digital lingerie catalog, which led to the Digital Shiatsu project for Nippon TV. Then there was the web and digital formats. My tech work probably comes to some extent from my father’s work at The Pentagon during the end of the Vietnam War. He was in Army communications and, as he says, “worked on the Monet”—DARPA’s beginning of the Internet. I used to go there with him as a kid.

I felt moving to NYC when I was 20 was like having a giant bookstore on my block, and free access. There was so much info, art, and history bits to glean while I was in my formative years. At first, I was drawing, painting, and then working as a music artist. Learning about video and editing led to our first music video production, “The Dominatrix Sleeps Tonight,” directed by Beth B, which is now in the MoMA collection (see the Blank City documentary). During these years, my friends Gretchen Bender and Amber Denker were experimenting in Computer Graphics out at the New York Institute of Technology, where pioneering CG research and experiments went on until 1984. I got involved with CG and multimedia conferences at the same time and met many interesting people, including Jaron Lanier, who developed virtual reality gloves.

Hontos: How did you get interested in developing an app?

Argabright: Seeing Bradbury, Asimov, and Arthur C. Clarke movies growing up, and later reading Russell Hoban, J.G. Ballard, John Brunner, and William Gibson got me thinking about survival in a more complex society. It was 1984. I was interested in tech waves. I did some research for Japanese business magazines, went to tech conferences on multimedia, computer graphics, future computing, interface and virtual reality, and I experimented with media as an artist. By this point in the mid-1980’s, Death Comet Crew was into a machine rock phase and playing with Max Headroom.

After meeting William Barg at The Palladium nightclub on 14th Street (now an NYU dorm) in 1986, he and I began a great run of electronic music and entertainment projects. In 1986—87, we co-created the audio-video performance Hip Tech High Lit for the Caravan of Dreams in Fort Worth Texas. The next day a Bass Brother’s jet took us out to Arizona to the site of the Biosphere to meet the Biospherians. Around that time we produced a movie idea with Gibson and Japanese director Sogo Ishii, and formed The Voodooists AV project based on Gibson’s idea of cybervoudou (we licensed “Queen Of Voudou” to Jonathan Demme for the soundtrack of Married To the Mob in 1989). The Voodooists released a 12” and a Japanese Laser Disc of Video Voudou for Toshiba / EMI / Kodansha in 1992.

We met many interesting people along the way, including Syd Mead, the “visual futurist” and designer of Blade Runner, Aliens, and Tron, writer Charles Lecht, Lance Williams of the New York Institute of Technology, and editor Ellen Datlow at Omni magazine. This involvement with science and technology included reading many great books by Alvin Toffler, Grant Fermajal’s The Tomorrow Makers, and Hans Moravec’s Mind Children. I was also involved with the Foresight Institute, a think tank devoted to questions around nanotechnology, AI, and biotech.

The production of the two CD ROMS in 1994 and 1996 allowed us to work with a new team of people on the edge of the newest media and programming at the time, and placed us right downtown in the early NY web boom. In 1997, Chuck Hammer asked me to produce a soundtrack for the television program Trauma: Life in the E.R., which took up the next five years. On each trip to Tokyo during this period I gathered glossy Japanese marketing images for cell phones, fronted with pop stars. At the time the Japanese were buying things from vending machines by touching their wallets to them, things we are just getting around to here in the US in 2013. This new app development is where world communication and screen technology are now going.

Hontos: Regarding new interfaces, the trend in music today has been more and more about going back to the technology of the 80s (analog synthesizer worship, etc.). As someone who’s dealt with that technology in the past, you’ve also embraced the updated methods of programming and playing live, and adapted to the current tech wave. I wonder if you can talk a bit more about why you’ve chosen to do that, how it changes your work, and where it may be leading you?

Argabright: Synthetic instruments came into our hands slowly, over time. Being able to have a synth in the rehearsal room downstairs by 1978 was lucky timing for The Futants. Then, receiving a Korg MS 20 as part of an exchange with a Dominatrix friend in 1982 was another lucky circumstance. Sitting in with the rare Synclavier in an uptown Studio in 1983, and recording on Peter Baumann’s custom-made German multi-track desk with oscillators up on 23rd Street in 1984, these were chances that just came together along the way. The streets led you places. But we don’t have those same machines now, over 30 years later.

I moved from drums, vocals, and playing some keyboards to programming drum machines, composing, and producing. At the same time, when recording tracks with engineers or producers, one couldn’t help but learn the processes. One hears about and then tries a certain new machine, so that your record won’t sound like everyone else’s. With the success of Dominatrix, I began to get deals that enabled us to go to a great studio (Unique Studios uptown) and utilize everything available there.

One upside of “the label signs and supports the artist system“ that was then dominant was that you could work with whiz engineers, enabling you to make “what you heard in your mind.” Seeing how much work and money it took, I kept towards producing ideas more than owning equipment or a studio because I was barely able to keep a place to live in during those years.

Over the years we have worked in both a pre-MIDI mode, where one had to synch machines by feel, and also a post-MIDI mode, where things could feel in synch but could also be stiff and odd-sounding. We have worked with Roland 303s and 606s, 909s, Akai samplers, and sound modules that enabled you to set up a sound group and then play it as events across the keyboard.

It’s 2013 and I am still using Reason software, as I do enjoy being able to set up the Redrum machine with more than the usual number of kicks, snares and hi-hats. There is the potential to continue building up the sounds beyond what one would usually produce and program, beyond what a drummer may be able to pull off.

The flexibility of using a drum machine allows me to do riphop one day and electronic psych the next. Also, the patterns can be deconstructed from a regular drum kit and placed into a grouping of more ambient percussion sounds, depending on the project, and on the song.

Hontos: How do these instruments condition your approach to composition?

Argabright: With hardware, one used to have to search and find, to know about in order to use, whereas now one can have all that on a laptop in a software version. Creating music to synch for TV, one becomes aware of timings within a one second duration. When scoring to picture, one second can be subdivided many times and can give a micro-expanse to operate within. With every group, every soundtrack, one learns and finds ways to get it done. The technology, and the engineers we usually work with, has led us to think of what else we want music to do. Envelope an audience in dozens of tracks moving in a live, surround-sound set-up?

We can do that. I come ready with my notes for the project and we sit in the cockpit studio and create for hours on end. Then comes a time where you just feel it is done, like a painting that doesn’t need more colors. I anticipate getting into 100-track songs, just to experiment and hear the density of the sonic when massing sounds in that way. New genre splices bubble up into the sun.

Hontos: In the 80s and 90s, before the internet, you didn’t have an electronic encyclopedia of music and art that was immediately accessible as a resource in the way that we do today. As a musician, how do you think about this expansion of information and sound?

Argabright: If jet plane travel was considered the analog of rock ‘n’ roll, then what is the sound of our current information age? We have plenty of clicks, hard-driving whrrr’s and machine sounds. Years ago music artists began making records based on damaged and manipulated CDRs, and then a phase of heavily edited forms emerged. I wonder: Is a new concrète coming? Is it here already?

Hontos: What are you listening to now?

Argabright: I’m just back from a West Coast tour with Black rain. Driving a van from LAX, we listened to Kevin Drumm’s quiet soundscapes and then Vatican Shadow as we passed downtown on our way to Glendale’s Complex. After the last show I stood outside on Weepah Way in Laurel Canyon, for some seconds, concentrating my attention up the street on the source of a series of sounds. A bird emits a complexly sequenced singsong.