David Geers

Today is not a time for monuments; it is a time for ruins. What front page of a newspaper is not splashed with images of social collapse, disaster, and grief that transfix us with their mournful beauty and fill us with lurid fascination? Whether in news photos of ecological destruction like that wrought by Hurricane Sandy, or of the social unrest rapidly destabilizing political regimes around the Muslim world and elsewhere, the image of the ruin has come to define our historical juncture. In art, as in popular cinema, a similar impulse holds sway. We have become a culture of melancholics, indulging in sublime devastation in any number of films that portend global and national disaster. (Just recall Hollywood’s recent offerings: Independence Day, The Day After Tomorrow, Deep Impact, Armageddon, I am Legend, Oblivion, This is the End, World War Z, White House Down, etc.) And when we seek escape from these extravagances in contemporary art, we encounter the ruin once more in the recent nostalgic exhumation of modernism, and lately, in images of antiquity in the work of Jeff Koons, Sara VanDerBeek, Justin Matherly, and others.1Today, in both Hollywood and its ostensible opposite, it is the image of a fragmented, mournful past that comes back to caution our present and foreshadow our future.

What impulse motivates this melancholia and what pressure turns our gaze back at the very moment when we are propelled so technologically forward? And what invisible horizon so frequently forbids us the futurism that marked the utopian visions of the past century? On the surface, this apocalyptic imaginary no doubt allegorizes our slow and gradual decline: the West’s abandoned utopian projects, its unrealized ideals that now return as fragments of an excavated history—a modern day vanitas. But might this fetish for ruins not also mark the recognition of a historical limit, whereby having reached an impasse and an end to the promises of capitalist Democracy and its most prestigious cultural forms, having exhausted all political options, drained all natural resources, and explored all aesthetic permutations, we now stand by the ruin unable to imagine a future beyond it? And dare we imagine this future by reading our images of ruins negatively, that is, as a utopian eschatology hiding precisely their opposite?

For Giorgio Agamben, this disjunctive connection of the past to the present forms the ineluctable condition of what it means to be contemporary, since contemporariness, as he puts it, “inscribes itself in the present by marking it above all as archaic. Only he who perceives the indices and signatures of the archaic in the most modern and recent can be contemporary.”2

For Agamben, even in the most timely lies a kernel of archaic otherness, of what stands forever out of reach—a remainder “unlived.” This “key to the modern…hidden in the immemorial and the prehistoric” connects us to the primitive and marks even the most avant-garde projections forward.3We see this dynamic played out in many modernist innovations seeking a return to the primitive as a lost origin, as well as in the image of the ruin that dialectically merges progress with obsolescence. As Svetlana Boym reminds us, even Tatlin’s monument to the Third International was “never free of the ‘ruin’s charm.’’ (and) despised by revolutionary thinkers and artists from Malevich to Guy Debord.”4

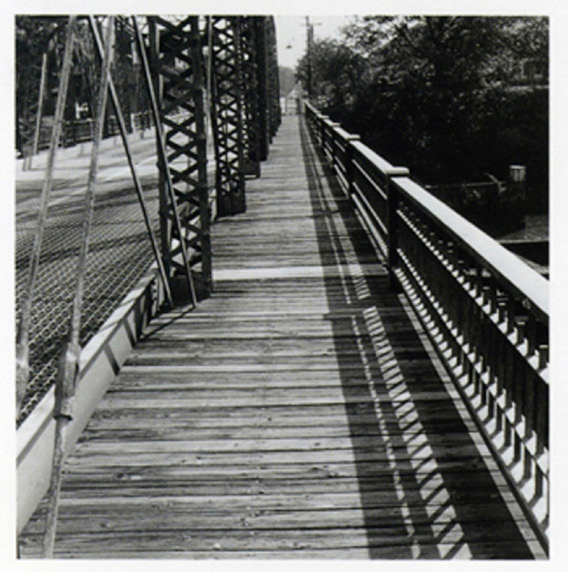

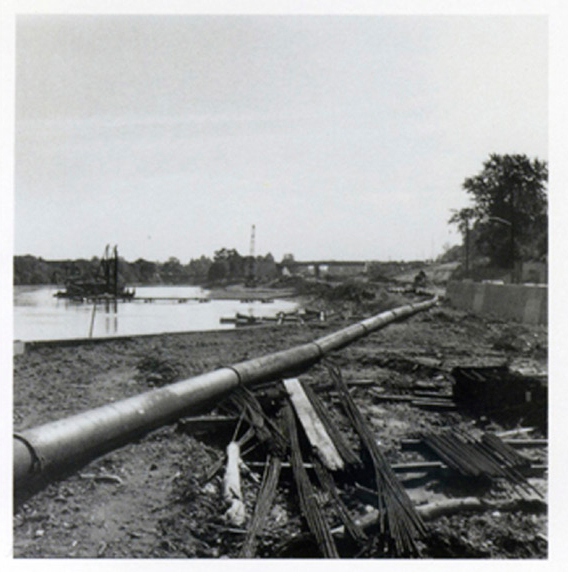

So, too, do we find the ancient ruin in the work of Robert Smithson, who, in “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey,” famously reinterpreted an industrial site as an archaic ruin of modernity, an abandoned monument to our lost civilization regarded as an imaginary future-past. Surveying its banal landscape, Smithson writes: “That zero panorama seemed to contain ruins in reverse, that is—all the new construction that would eventually be built. This is the opposite of the ‘romantic ruin’ because the buildings don’t fall into ruin after they are built but rather rise into ruin before they are built.”5

For Smithson, this site, and our present within it, represented “[a] Utopia minus a bottom,” a place of holes and “monumental vacancies that define, without trying, the memory-traces of an abandoned set of futures.”6

Robert Smithson, from “The Monuments of Passaic”

Today, this knot between past and future continues to be the tacit covenant made between contemporary art and its ancient moorings. For, while antiquity returns as a decadent reliquary adorned with alien blue spheres in the work of Jeff Koons, it is mournfully displayed in images of Roman women alongside Minimalist plasters by Sarah VanDerBeek. In Justin Matherly’s work, recreations of ancient statues precariously perch on ambulatory equipment like so many geriatric invalids lumbering out of the past. Or consider Ugo Rondinone, who satirizes our fetish for fossils and our contemporary primitivism at the same time, producing megalithic sculptures of standing men equally reminiscent of an excavation site and an historical museum. These stone sentinels coyly announce that our culture, too, will fade and fill the archaeological displays of the future. Our plazas, our strivings, our skyscrapers are merely tombs left for some visitor to archive or to plunder. But these are not isolated cases and alone may not be enough to capture the apocalyptic and melancholic tenor of today’s cultural production.7

Indeed, some would argue that this apocalyptic (dare I say, Romantic?) imagination is nothing new. For Andreas Huyssen, the whole tradition of modernist thought through postmodernism can be seen as marked by a catastrophic imagination, with the ruin as a central aesthetic and epistemological topos.8Dreams of ruin, destruction, and rebirth also informed the rhetoric of most 20th Century artistic avant-gardism. “We stand on the last promontory of the centuries!” Marinetti proclaimed in 1909. “Why should we look back, when what we want is to break down the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and Space died yesterday.”9Tristan Tzara made a similar pronouncement in his 1918 Dada Manifesto when he extolled, “Let each man proclaim: there is a great negative work of destruction to be accomplished. We must sweep and clean.”10Even Malevich joined this chorus in praising the negative force that separated the old age from the new, announcing, “Everything has vanished, there remains a mass of material, from which the new forms will be built.”11

In popular culture, too, apocalyptic imagery has been the mainstay of Hollywood since the early fifties, when apocalypse was equally signified by a menace within our stead and an otherworldly visitor from outside coming to lay waste to our civilization. But this appetite for destruction—for our own destruction—has noticeably picked up pace of late. Now, a steady torrent of apocalyptic imagery beckons and warns against Doomsday all at once, as if driven equally by the traumas of 9/11, intensifying natural disasters, and a wish-fulfillment fantasy for more of the same.12

Too often, our virtual and actual disasters blur, as representation and reality intermix in a nightmarish mise-en-scène—as in the shards of ruin left of the World Trade Center or in the cinematic deluge and apocalyptic landscape left by Hurricane Sandy. Visitors to these grim sites could recall everything from paintings by Caspar David Friedrich to films like Independence Day or The Day After Tomorrow. So why demand more of this in our leisure viewing?

For Freud, the compulsion to repeat traumatic events was tied to the death drive, Thanatos, which functioned as a counter to the instinct for self-preservation embodied in Eros. As a primitive precursor to Eros, the “death instincts” compel the subject to return to an earlier, inanimate state of matter, since, as Freud conjectured, “inanimate things existed before living ones.”13However, this circuitous path onto death has to be in the subject’s “own fashion,” so he can take an active rather than passive role in his eventual fate. Today’s image of the ruin, the replay of disaster, could thus be conceived as an attempt at mastery, a psychic shielding against trauma through its perpetual replay within the aesthetic sphere. Regarded through this optic—as a tropism towards death, but on our own terms—our apocalyptic theater attempts to master the more insurmountable, real ecological and political disasters waiting in the wings.

Freud famously illustrates the compulsion to repeat negative events with the case of his grandson’s repetitive game of fort da. He observed how the little boy compulsively threw a spool out of sight while exclaiming fort (gone) and retrieved it by its string while exclaiming da (there). For Freud, this repetitive act mastered the trauma of loss (of the child’s mother leaving), and, at the same time, generated the pleasure produced by the object’s reappearance. To follow this logic of negation and return: Isn’t the constant replay of our destruction in film, our replay of our national emasculation in images of an exploded White House (Independence Day, Olympus Has Fallen, White House Down, etc.), and our reconstitution (often by a phallically empowered President), just such a game of fort da? This repeated loop of national disaster returns us to the state of anxiety that we needed to anticipate the initial trauma, and rebuilds us anew as a militarized, over-prepared nation. Such is the ideological narrative told by most Hollywood film and eagerly consumed by patriotic audiences every summer—a narrative of rebuilding, not of radical reconstruction. Yet, hidden within this dynamic resides a negative utopianism as well, since, in so rehearsing to destroy the present, we also posit a completely new future on the old one’s ruins.

For artists especially, this ritual may have a certain valence, though it is doubtful that many now are conscious of their own utopian longings. After all, in their deconstructions, how many want to demolish the bourgeois edifice of Painting once and for all or negate the grandeur of Sculpture in order to get to its other side and thus radically reconstruct the discipline? Such an act would be too total, too apocalyptic. To be sure, most of us prolong the demolition in an “amorous deferral” of death by dwelling on the artisanal object in its shards—by insisting on its hierarchies, its connoisseurships, its property structures.14Moreover, if such demolitions and reanimations had a utopian kernel in the century before, they have since become mostly ceremonial today: a “modernist hangover.”15Our many deconstructions, excavations, reuses, and repurposes bear witness to this fact; we are suspended in the deconstructive act (fort) with few utopian proposals following our ritualized negations. Having thus ceded innovation to the technical sphere, we now rely on our culture to bury and reanimate—to produce more spin-offs and sequels.16

More than simple nostalgia, or search for market guarantee, our tick for the redux may also reveal a limit of production: a crisis of originality brought on by unprecedented technological visibility, where too many equally irrelevant novelties compete side by side in full view, and so reduce the artist to a melancholic posture of mourning. We don’t live in a smaller world; we just have a better flashlight, an artist friend once said.17Indeed, as the cycle of cultural obsolescence accelerates, the only viable posture left may be to contemplate what is still and garbed in the fabric of the ostensibly eternal, even if as a fragment. For Walter Benjamin, this fixed gaze was the essence of melancholy, where the melancholist regards the “facies hippocratica” of history presented to him as a solemn parade of ruins. For us, it presents itself in the guise of so many uncannily reanimated artistic forms and in fantasies of our own destruction.18

Yet, what are the alternatives? What kind of utopianism is called for, when one cannot imagine, cannot plan, cannot map beyond one’s immediate field of vision? This, after all, is commonly the province of technologists, entrepreneurs, and engineers—not cultural producers. Even our familiar art world utopianism is often moored in the language of retrospection in its melancholic recall of past avant-gardism, with its monuments to philosophical saints, its readymades, its monochromes, its fort da. And though utopianism is doubtless always conditioned by an archival impulse, it now seems to gesture only through historical commemoration, as if marshaling to recall rather than advance, or to advance only through a theatre of citation.19How does one pierce this melancholic enclosure and begin to imagine what lies outside our current amusement park of ruins?

Perhaps the task is to read these cinematic and artistic attacks literally—as a wish-fulfillment fantasy—in order to identify their hidden utopian longings. If we look only at the devastation of our cities in film, we may, for instance, imagine a future with no landmarks, since all such signs of national identity may be irrelevant to some possible, unified humanity. As the collective tremors of the global economy now foreshadow, such unification is already well underway, at least economically. It has simply to be recognized consciously and is, instead, replayed traumatically as a game scenario, a dress rehearsal. So, too, do we see in the specter of an often mechanized alien-adversary the glimmer of a future post-humanity already envisioned in the advances of war-accelerated medicine and 3D printing. The future we so anxiously try to incorporate is one where distinctions of animate and inanimate cease to matter, where we triumph over death by merging seamlessly with the un-living. Our films project such chimeras as external threats from the future, but only to screen out more proximate images of military hospitals in our present.

In art, too, our demolitions may long for what lies on the other side of the material work yet is cloaked in the language of anxiety. For when we do finally destroy a painting, as does Valerie Hegarty, or a sculpture, in the manner of Cornelia Parker or David Altmejd, does it remain a shattered corpse for us to forensically decipher and reconstitute? Or can we, rather, go further and through to the other side of material decay until materiality turns into its opposite and transforms into pure signification, pure data? Such would be the condition of so many works relying on a forensic reading of clues, of aesthetic apprehension as the processing of information. We misrecognize their language, nostalgically, as the rhetoric of matter, whereas it is already—and has been for a while—a language of code. Thus, even the most earthy and material works now tacitly anticipate their eventual transmutation in some future, immaterial archive. On the other side of the corpse lies the cloud.

In the end, to long for ruin (as we collectively seem to do) is to long for a world that does not need national monuments, private property, or class distinctions—a world where the machine has finally become part of us, and we have become indistinct from the inanimate—no longer living or dead. In Warm Bodies, a recent zombie rom-com, it is too long for the Earth, which, once purged of such segregations, is repopulated by a society no longer in need of its protective walls. Such would be the utopian path suggested behind our screen images of ruin. Our apocalyptic scenes presciently play out all the possible scenarios of our intractable economic and technological course. Seen as a wish-fulfillment fantasy, the contemporary language of crisis is the dreamwork of historical transformation.

But such fantasies may be quaint at best and may serve a greater purpose, as well. Part talismans and part hypnotic runes, they, and we who produce them, serve to blot out the presentiment of an ecological doomsday all too near, and an ever-expanding surveillance society mobilized by a State of eternal terror—a State more enduring than our fetishized fragments. In the end, the image of the ruin masks a more grim reality by substituting an image of static decay for one of overproduction.20It substitutes a dilapidated monument for an accelerated Capital working in a dizzying feedback loop of perpetual crisis: a process of spiraling obsolescence and social division, of apocalyptic flows of people, data, things, emerging interchangeably from some yet undiscovered intelligent material only to disappear again in a sublime indistinction. It is against this apocalyptic scenario that the modern image of the ruin stands as a shield and offers us its mournful and stationary solace.

Endnotes

1. For more on this return of modernism, see David Geers, “Neo Modern,” October 139 (Winter 2012), 10–14.↩

2. Giorgio Agamben, “What is the Contemporary?” in What Is an Apparatus and Other Essays, ed. Werner Hamacher (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2009), 50. ↩

3. Ibid, 51.↩

4. Svetlana Boym, “Tatlin, or, Ruinophelia,” Cabinet 28 (Winter, 2007/08), http://cabinetmagazine.org /issues/28/boym2.php↩

5. Robert Smithson, “A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey,” Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack Flam, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 72.↩

6. Ibid.↩

7. For more on this ruin lust in contemporary art, see Brian Dillon, “Decline and Fall,” http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/decline_and_fall/ One can also add to this trend, recent work by Adam Cvijanovic, Ellen Harvey, Diana Al Hadid, Valerie Hegarty, and others. Some of these artists were also included in a recent show on ruins called The Stumbling Present: Ruins in Contemporary Art at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara.↩

8. See Andreas Huyssen, “Nostalgia for Ruins,” Grey Room 23 (Spring 2006), 6-21.↩

9. Tommaso Marinetti, “The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism,” in Art in Theory 1900–1990, eds. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1992), 145-149.↩

10. Tristan Tzara, “Dada Manifesto 1918,” in Art in Theory 1900–1990, eds. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1992), 248-253.↩

11. Kasimir Malevich, “From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting,” in Art in Theory 1900–1990, eds. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1992), 166-176.↩

12. One can add to this fascination the latest interest in post-anthropocentric thinking in the arts and elsewhere, embodied equally in the popularity of Alan Weisman’s bestselling book The World Without Us; the influence of “Speculative Realism” in philosophy, which contests the primacy of the human actor; and in “Accelerationism,” which attempts to imagine and prepare for a post-anthropocenic technological singularity beyond and without man. For several such recent considerations in art, politics, and design, see: Katy Siegel, “The Worlds With Us”: http://www.brooklynrail.org/2013/07/art/worldswith-us; Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek #ACCELERATE MANIFESTO for an Accelerationist Politics: http://criticallegalthinking.com/2013/05/14/accelerate-manifesto-for-an-accelerationist-politics/and Benjamin Bratton, “Some Trace Effects of the Post-Anthropocene: On Accelerationist Geopolitical Aesthetics”: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/some-trace-effects-of-the-post-anthropocene-on-accelerationist-geopolitical-aesthetics/↩

13. Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, translated and edited by James Strachey (New York: Norton, 1961), 46-47.↩

14. In “Painting: the Task of Mourning,” Yve-Alain Bois refers to Robert Ryman’s protracted demolition and mourning of modernism as an amorous deferral: “Ryman’s dissolution is posited, but endlessly restrained, amorously deferred; the process (which identifies the trace with its ‘subjective’ origin) is endlessly stretched; the thread is never cut.” YveAlain Bois, Painting as Model, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998), 232.↩

15. David Levine in conversation. For more on this vestigial rhetoric of negation and criticality see: “Critical Language: A Forum on International Art English,” by The Editors, May 27, 2013: http://canopycanopycanopy.com/podcasts/54-critical-language-a-forum-on-international-art-english↩

16. For more on this trend in film production see: http://www. cnn.com/2013/07/05/showbiz/movie-sequels-gallery↩

17. Kanishka Raja in conversation.↩

18. Walter Benjamin, Origin of German Drama, trans. John Osborne ( London: Verso, 1994), 166.↩

19. For more on this archival impulse as it animates utopian formations (such as OWS) see Gregory Sholette: OCCUPOLOGY, SWARMOLOGY, WHATEVEROLOGY: the city of (dis)order versus the people’s archive, Art Journal: http://artjournal.collegeart.org/?p=2395↩

20. This is to echo Andreas Huyssen’s distinction between the ruin and rubble where the ruin assumes the temporality of gradual decay while rubble speaks of instantaneous destruction and rapid obsolescence. “Authentic ruins,” as they still existed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, seem no longer to have a place in late capitalism’s commodity and memory culture. As commodities, things, in general, don’t age well. They become obsolete, are thrown out or recycled… The ruin of the twenty-first century is either detritus or restored age.” Andreas Huyssen, “Nostalgia for Ruins,” Grey Room 23 (Spring 2006), 6-21.↩