Kathie Smith

“I think we need more industry professionals hustling for independent and experimental media—who appreciate work that is not primarily coming from a place of financial motivation.” This is not exactly a statement you expect to hear when you sit down to interview someone about film, but it perfectly represents the aptitude of producer and programmer Steve Holmgren. “I didn’t know if I was going to get into this or not, but I am planning to go to Law School next fall so I can be better at what I’m doing and be a stronger advocate for artists.”

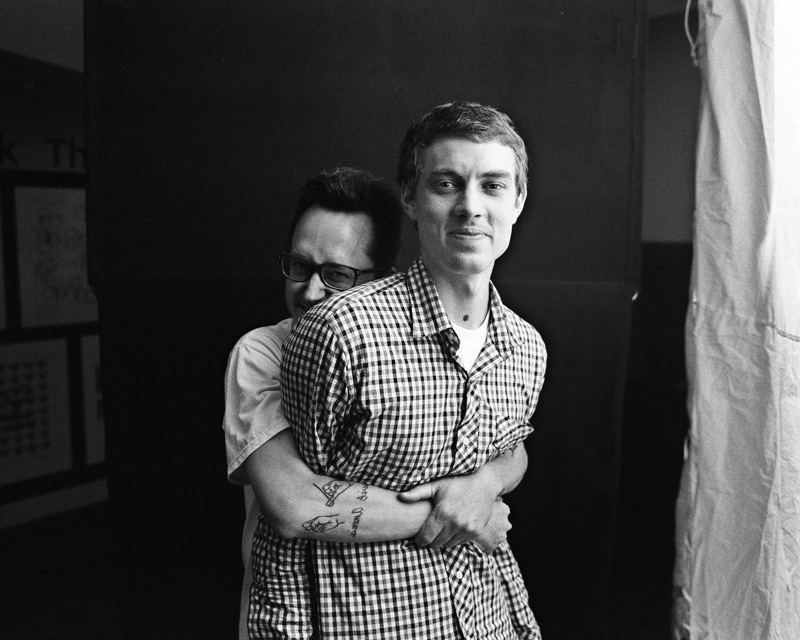

Holmgren admitted as he enthusiastically talked about the need for challenging and creative films. A cinephile with a business degree, Holmgren is one of the unsung champions of the film industry, working both behind the scenes and under the radar in New York City’s hardscrabble world of independent production and alternative exhibition.

Holmgren has recently made a name for himself programming at Union-Docs, a forward-thinking screening and event space in Brooklyn, and independently producing awardwinning films under his label Steady Orbits, including titles as diverse as John Gianvito’s politically resonant omnibus Far From Afghanistan (2012), Marie Losier’s pandrogyne love story The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye (2011), and Cory McAbbe’s charming childhood odyssey Crazy and Thief (2012). But his longest-lasting collaboration has been with Matt Porterfield, one of the most exciting young filmmakers working today. When Cinema Scope magazine named Porterfield one of the Best 50 filmmakers Under 50 last year, Porter-field was well under that 50-year-old mark by 16 years.

Of Porterfield’s three feature films—Hamilton (2006), Putty Hill (2010), and I Used To Be Darker (2013)—Holmgren has worked to some degree on all three and served as producer on the last two. Their working relationship has organically evolved over the years into a synergetic collaboration of financial brains and creative brawn. By Porterfield’s account, Holmgren has an exceptional ability to multitask while maintaining the attention to detail he lacks; and by Holmgren’s account, Porterfield is a talented creative perfectionist who deserves logistical support. But Holmgren is more than just business and readily effuses with the best of Porterfield’s supporters when asked about his films: “Matt has a tremendous amount of empathy for people, and a special way of experiencing life and putting it on screen. I think he has a real desire to experiment and expand and not do the same thing.”

Porterfield’s most recent film, I Used To Be Darker, a drama about those rough patches in life that can either painfully wax or quietly wane, might be more conventional in terms of plot than his previous two films but is nonetheless cut from the same strikingly empathetic cloth that Holmgren describes. With a primary cast of four, I Used To Be Darker celebrates our need for companionship and the potency of creative catharsis, in this case, manifested through Ned Oldham and Kim Taylor, the film’s two lead actors who are musicians both on and off the screen. What the film accomplishes by reeling in the formal ingenuity is to clear out some of the cerebral machinations for a more gentle space of emotional resonance. Both Porterfield and Holmgren are happy with what the film has already accomplished: Premieres at Sundance and Berlin earlier this year, a healthy dose of critical and popular praise, and a subsequent US distribution deal with Strand Releasing. On the eve of its theatrical release this Fall, however, they also acknowledge that, as the follow-up to the successful follow-up, the stakes are inevitably higher.

—

Born in West St. Paul, Steve Holmgren grew up in Roseville, Minnesota, not necessarily watching movies, but learning the skills of buying and selling. “My father is an auctioneer and antique dealer in the Twin Cities, and I grew up around the art of the deal, which certainly left a strong imprint on me.” After graduating from business school at Boston University in 2005, Holmgren moved to New York City with a notion of putting his degree to work in a different way. “It’s kind of funny—I thought I was going to work in real estate, but I only made it about a week.” After cleaning out his desk at a real estate firm, Holmgren found himself doing what any good New Yorker would do with some free time: going to movies. But not just any movies—when Holmgren reminisces about the films he saw during this time, he easily rattles off names that belong to the upper echelon of filmmaking innovation: Peter Watkins, Pedro Costa, Carlos Reygadas, Harmony Korine, and John Cassavetes.

Film was something Holmgren gravitated toward in college, but this was different. In need of a job, he started to consider the industry of film as a viable and compelling pursuit, and, without any formal or academic experience in film, furiously began applying to everything he could find. After multiple attempts, he finally landed a position with Mark Cuban and Todd Wagner’s up-and-coming HDNet Films, but not without a little luck and a serious amount of effort. The person hired for the job fell through, opening up a spot for Holmgren: “I found out Thursday night I was going to get the chance to interview Monday morning and spent all weekend on this paper about strategic difficulties they might be facing and how they might deal with them. They thought that was kind of weird, but I guess they were also impressed on some level and I got the job.”

HDNet began as a high-definition cable channel in 2001, a time when HD technology was still somewhat of a novelty for consumers. For all of HDNet’s failures (it was quietly absorbed in an AEG joint venture last year and rebranded as AXS TV), its indie film production arm was part of a bold distribution platform that may have been a little ahead of its time. They were at the forefront of VOD distribution and challenging the ways that films could be produced and released. Thinking outside the box from a business standpoint, HDNet began experimenting with a “day and date” strategy— simultaneously releasing films theatrically, on DVD and on-demand. Steven Soderbergh’s Bubble (2005), produced by HDNet Films and Cuban’s 2929 Productions and released by Magnolia Pictures, was one of the first of its kind, and although it was hardly a financial success, it’s a model that has been mimicked and adopted by distributors across the board.

As office manager at HDNet Films, Holmgren was able to dig in on various aspects of film production, sales, distribution and administration. “It was just small enough where I got to know everybody fairly well and do a bit of everything.” He kept a close eye on HDNet’s festival and international sales, an area of the business he found interesting. When things started to go south and Holmgren was laid off, he decided to take the opportunity to travel and work at some of the film festivals he had been in contact with such as Sundance, Tribeca, and the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam. He also connected with his hometown scene, programming primarily with Sound Unseen but also the Minneapolis-St. Paul International Film Festival. It was during this period that he developed a relationship with the New York-based Cactus Three Films, responsible for docs like loud QUIET loud: A Film About the Pixies and Devil’s Playground, and became their freelance international sales agent.

But in his role as a sales rep, he felt like he was losing the connection to the more creative side to the business. “I started to get a little turned off when it was more about advertisers and numbers than the actual film.” Holmgren’s prophetic divergence was to start working with The Robert Flaherty Film Seminar in upstate New York, an incredibly influential force in the world of meaningful independent film, with an emphasis on the equivocal word “meaningful.” Regardless how you define that word, The Flaherty, something of a think tank, is an organization that challenges its participants to ask tough questions about film and filmmaking—not only artistic and logistical, but also moral and political. Meanwhile, Holmgren also found work with Gartenberg Media Enterprises, a boutique company dedicated to the archiving, repurposing and distribution of a strange array of silent and experimental films. Finding the right combination of vibrant left-brain fuel and constructive right-brain tasks was key for Holmgren, and he seemed to find that in his willingness to explore the niche areas of the New York’s eclectic film world. “ GME and the relationships I built through the Flaherty helped solidify the notion that the industry around film and art exists because of artists, and without them, none of us would have jobs—some-thing Jon Gartenberg’s friend and mentor Adrienne Mancia instilled in him that he wouldn’t let me forget.”

Much of Holmgren’s varied interests can be found in the programs and events he has organized and curated at UnionDocs over the past four years. Having arranged a couple of successful screenings for the space on a freelance level, he was eventually hired on a more full-time basis. Union-Docs is one of those unique spaces that balances the needs for exhibition, collaboration and dialogue. Holmgren and founder Christopher Allen position themselves somewhere between the industry and academia, and are committed to filling that gap with an indispensable schedule of events, as well as, at the same time, running an innovative artist studio program—The UnionDocs Collaborative—which pairs 12 documentary artists from around the world for a ten-month intensive experience in the history, theory, and production of documentary arts. In his role as the organization’s programmer, Holmgren has facilitated a number of events that represent a who’s who of the documentary and experimental film scene: filmmakers Albert Maysles, Jonas Mekas, Jem Cohen, Peter Hutton, Bruce McClure, Nan Goldin, and Tony Conrad; as well as leading scholars like Scott MacDonald and P. Adams Sitney. “UnionDocs has been my home base for over four years now and it is continuing to evolve in exciting ways. To be able to bring so many tremendous filmmakers and documentary artists together for countless unforgettable conversations has been incredibly rewarding. I am very pleased with the space the programs have been able to occupy and for the opportunity to be considered amongst incredible inspirations such as Amos Vogel’s Cinema 16, The Collective for Living Cinema and the Robert Beck Memorial Cinema amongst many others.”

It was around the time that Holmgren started at UnionDocs that he was co-programming a series of new American indies for the Amsterdam International Film Festival with friend and filmmaker Aaron Katz. Katz suggested he take a look at Hamilton, a film he had seen at festivals while touring with his own film, Dance Party, USA. Seeing Hamilton for the first time was something that Holmgren describes as transformative for him. “I had never heard of Hamilton and was really blown away. It announced a vision and talent on the US scene that was really exciting.” Not only did he program the film in Amsterdam, but he also began to foster a friendship with Porterfield through it and their mutual interest in film. The deal was sealed when they met in 2008 while Porterfield was participating in IFP’s Emerging Storytellers program with his new script Metal Gods. Holmgren wanted to continue finding places to book Hamilton and concurrently kept in close contact with Porterfield as Metal Gods progressed. Porterfield admitted that their working relationship developed naturally: “I’ve been really lucky to have built longstanding relationships with key collaborators that came together organically. And with Steve it was easy.” And after working with Holmgren for over four years on two hard-fought features, Porterfield is thankful to have him by his side: “I say it sort of jokingly, but for me, he’s more than a producer—he’s the best manager I could have.”

—

Matt Porterfield grew up in Baltimore. After a stint at NYU, he returned, hungry to make a film. Five years in the making, Hamilton established Porterfield as a filmmaker with a distinct vision—one that showed a keen openness to his characters and an intuitive eye for spaces. At just over an hour, Hamilton is slight to the point of perfection, but there is also a palpable desire to portray underserved walks of life without glossy affectation, a rarity on the big screen or little screen. Although these are qualities that would carry over, to various degrees, to his second and third features, the stunning thing about Hamilton, a debut film that was largely funded by family, friends and creative fundraising, is the clarity of Porterfield’s singular aesthetic.

Shot on 16mm in Porterfield’s own neighborhood of Baltimore, for which the film is named, Hamilton chronicles the wayward relationship between Lena (Stephanie Vizzi) and Joe (Chris Myers) over the course of a couple summer days. Lena, a young mother, is heading to her grandmother’s house for a month and is hoping to reconnect with Joe, her boyfriend and father of her child, before leaving. Lena and a friend break into his basement apartment to leave him a note, which she scrawls across a page in a porn magazine she finds by his bed:

“WHEN R U COMING OVER THE HOUSE?”

For all the melodrama implied in this opening, the magic of Hamilton is in its defiance of exaggeration and the clichéd tropes of dramatic structure in film. Allowing the essence of people and place to guide the audience, Porterfield tells his story with an economy of verbal exposition and a surplus of atmospheric subtlety. We first meet Joe as he is taking a break from mowing a lawn and playing with the dog in the yard. His boss stops by to let Joe know that Lena is looking for him, which gives way to another break for a phone call, a smoke, and a chat with his sisters. Joe’s efforts are a scenario of a glass half full—half trying and half giving up—but the weight of the former overshadows the latter as we connect with the film’s sympathetic disposition toward Joe. His quiet frustrations are epitomized in a silent car ride with his mother (done in a single shot and reportedly cut down from 10 to a still-very-uncomfortable 3 minutes); his equally restrained compassion is manifested in the bulk of the film’s finale.

Porterfield and his cinematographer, Jeremy Saulnier, provide a stunning centerpiece to the film when they follow Joe as he walks on a casual yet purposeful journey through Baltimore, over the hill and through the woods to the road where his mom, coincidentally, sees him and picks him up. It’s a formally elaborate and yet emotionally meditative sequence that could easily be heralded as a conscientious emblem for the film. Similarly representative are a trio of shots in the film that capture spontaneous bursts of life within the space of the still film frame: a kid on a BMX bike going to and fro across the screen, providing playful movement with the title sequence; the spring-loaded emergence of a young girl’s head from a trampoline; and three kids on swings, flowing in and out of the open air composition.

The film premiered at the Wisconsin Film Festival in 2006 and spent much of the next year traveling the festival circuit, including the Maryland Film Festival, Stockholm International Film Festival, Denver Film Festival, and Nevada City Film Festival. It also earned limited runs at Anthology Film Archives in New York and Facets Cinematheque in Chicago. Hamilton’s reception was a slow and perhaps small wave by Hollywood standards, but the film gained a small army of vocal supporters, not only in Holmgren, but also in Richard Brody for the New Yorker, who called the film “One of the most original, moving, and accomplished American independent films in recent years,” and critic Phil Coldiron for Cinema Scope, who cited the film as “remarkably ambitious…both formally and conceptually.”

Hamilton was starting to wind down when Porterfield began writing and planning for his second film. Motivated to build on what he had learned from his first feature, Porterfield started working on another Baltimore-based story titled Metal Gods, about two Baltimore teenagers. Porterfield confessed, “There was pressure to write a stronger screenplay, and I wanted to push myself—it was more ambitious, it was a larger ensemble cast that I was trying to piece together, it had a number of ambitious locations, and the whole music element.” Securing funding for an indie film is an arduous task under any circumstances, but in 2008, when some of the final pieces were being put together for Metal Gods, it proved impossible. After the stock market crashed, it was very clear that the financial picture was not going to get better anytime soon. Metal Gods got shuffled to the back burner (where it continues to simmer), and Putty Hill emerged as a devil-may-care project that, in some respects, lightened the load of expectations. Porterfield explained, “When it didn’t come together, it felt like a free pass. We had nothing to lose, and we had to put together the scraps. It took a lot of pressure off.” Porterfield and his crew decided to take a risk with the $20,000 they did have and shoot a quick, improvised film from a five-page treatment—available on the Putty Hill website—that Porterfield had written on the fly for some of the cast they had assembled for Metal Gods.

Despite the unusual circumstances of its production, Putty Hill is a natural companion to Hamilton that emphasizes people and place over plot. But, because the reigns had been let go on a traditional script, it developed into something even more freeform and unconventional. Instead of being forced into a corner, Porterfield reacted audaciously to what could have been paralyzing restrictions of time and money, highlighting what are probably his natural tendencies as a director to not only embrace the blurry line between documentary and fiction, but also to trust his instincts on his material, crew, and actors.

Putty Hill is the documentation of a group of people who are all somehow connected to a young Baltimore man named Cory who has recently died from a drug overdose. In the day before the funeral, we meet Cory’s younger brother who is engaged in a paintball battle, his older sister who is off the Greyhound bus from Delaware, his friend he met in prison, his uncle who is a tattoo artist, his sad mother and pragmatic grandmother, a cousin from Santa Monica, and a host of other acquaintances. Their stories have less to do with Cory than the environment—full of hope, joy and sadness—that he left behind.

Cory is a fictional device in Putty Hill, but much of the subtext for the film is built and drawn from the very real experiences and lives of the actors, lending a certain amount of unadulterated verisimilitude that can be hard to find even in documentaries. Taking the nonfiction ambiance one step further, Porterfield audibly emerges from behind the camera to interview characters as he “catches” them in a quiet moment. This oft-used talking head tactic is surprising in a number of ways, but mostly in how it does nothing to disrupt the intrinsic flow of the story. It is almost counterintuitive how the interviews, peppered throughout the film, pull you out of the action, making you fully aware of a camera and a director, and then carefully place you right back into the fictive space of cinematic illusion without missing a beat.

Much of the credit goes to editor Marc Vines, but it is also an attribute of understanding that the setting and the characters are in many ways connected—Spike in his home tattoo studio; Cody at the skate park; a group of young adults smoking, drinking, and hanging out at the river; and, in one of my favorite scenes in the film, Cody’s mom composing and singing a song in her kitchen. These are not sets but the lived-in spaces of the characters. The glow that comes from these scenes acknowledges the power of empiricism as a source not only for the actors, performing in their own skin, but also for the audience willing to give itself over to the experience of the film.

For all its somber overtones, the tenderness that Putty Hill has for the heartbreaks of life is equal to the sensitivity it has for its characters to roll with the punches. Cory’s death is just a pretense to take stock in a moment, and we are along for the ride. That ride ends, literally, in the dark when Cory’s sister and her friend go to the house where Cory last lived and presumably died. Searching for a sense of closure, the two girls explore the abandoned house with the light of their cell phones, but find little more than a creepy, half-lived in room and the fading memory of a guy they once knew. But those memories are no different than the everyday moments from which Putty Hill is built—mundane and idiosyncratic, beautiful and routine, plaintive and sanguine.

If you look at it from the right angle, Putty Hill was a huge success. In 2010, it snagged a place for its world premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival—a festival that, in recent years, is considered more innovative in its programming than Cannes—and received its North American debut as an official selection in the SXSW Film Festival. These screenings, and its inclusion in a number of other high-profile festivals (BAFICI, Viennale, CPH PIX, Thessaloniki, Era New Horizon), meant that Putty Hill was getting a much wider reach right out of the gate. The film was picked up in the U.S. by Cinema Guild, released theatrically in early 2011, and then put out as a handsome two-DVD set that includes Hamilton. When critics were sizing up the year in film, Putty Hill found its way to many top ten lists around the world. Critical success had been won, but it didn’t necessarily translate into financial success. The film’s initial bare-bones budget was padded for post-production, and box office returns were very modest by any standards. The reality is that making a film on a shoestring—and we are talking about a shoestring of the 99%, not a half-million dollar Blair Witch shoestring—means that most people involved don’t get paid.

But without pause, Porterfield started working on his next one. He resurrected a script about a foreign student working the beach tourist trade in Ocean City, Maryland, and recruited Amy Belk to co-write. When they finished, they had 89 pages (a far cry from Putty Hill’s five), a handpicked cast of enthusiastic non-professionals, and enough financing to see the light at the end of the tunnel. Where-as Hamilton and Putty Hill were experimental features by necessity, I Used to Be Darker displays the more deliberate steps of a skilled director with something close to the financial means. Porterfield’s conscientious hand is clearly present, but I Used to Be Darker is a significant departure for the three-film auteur. A set piece of subtle moments and messy emotions, the film taps into Porterfield’s personal experience with divorce, both his own and that of his parents. Whereas Hamilton and Putty Hill were portraits of youthful fragility and perseverance, I Used to Be Darker turns its camera to the shattering realities of adulthood. Conflict is a matter of course and melodrama is a schema. The film delivers on these standard-fare elements, however, with surprisingly understated panache.

I Used to Be Darker dives into the emotional tangle of a dissolved marriage, with a college daughter and a visiting niece in tow. Taryn (Deragh Campbell) is from Northern Ireland and is working for the summer, secretly on the lam, in Ocean City, Maryland. Her parents think she is in Wales, but reconciling with them is secondary to Taryn figuring out her more immediate problems. At a juncture and not knowing what to do, Taryn shows up on the doorstep of her aunt, uncle and cousin in Baltimore, unknowingly walking into a maelstrom of irreconcilable differences. Bill (Ned Oldham) and Kim (Kim Taylor), both musicians, are in the thick of the bitter details of divorce—she is taking the last of her things; he is left in a large empty house. Emotions are raw and occasionally explosive, but the two of them attempt to maintain some civility for the sake of their daughter, Abby (Hannah Gross). Just as Taryn appears for an unannounced visit, Abby arrives home for the summer from college. Although her dad’s near catatonic state around the house frustrates Abby, the bulk of her anger is concentrated on her mom.

The fabric of the film is woven together with the unpredictable affairs of the heart, but I Used to Be Darker finds its infrastructure in music. The title itself is taken from the Bill Callahan song “Jim Cain,” which resonated with both Porterfield and his co-writer Belk. The song’s lyrics were a template for the atmosphere of the film: “I used to be darker, then I got lighter, then I got dark again. Something too big to be seen was passing over and over me.” That overhanging mass is very much present in the film, individualized for Taryn, Abby, Kim, and Bill’s very personal trials.

But even within the construct of the story, music is tantamount. Taylor and Oldham (brother to Will) were chosen as actors because they were musicians, and Porterfield talks at length of how their music informed the script. As a result, the story embraces the creative impulses of Taylor and Oldham in their respective roles. You intuit that their musical compulsions initially brought them together, but now, in their un-coupling, their creativity has evolved into the thing that will enable them to transcend. The film revels in all aspects of the diegetic use of music—albums on the record player, jam sessions in the basement, noise rock in an underground club, and, at key moments in the film, full-length songs performed in a bubble of isolation by Bill and Kim. Taylor’s performance, the consummate punctuation point for the film, is one that will stay with you long after the lights come up.

Again working with Saulnier as cinematographer, Porterfield creates some beautiful spaces within the frame of the film. Shot in luxurious widescreen ‘scope, the airy ambiance is augmented by a sound mix, supervised by Danny Meltzer, that blissfully immerses you into the textured atmosphere of summer, almost a counterpoint to the stewing emotions it surrounds. But it would all be an empty shell without the incredible performances the actors bring to the screen. Having worked with non-professional actors on three features, Porterfield’s intuition can-not be overstated. Asking more of his cast than ever before, he is nevertheless nonchalant about how they were chosen: Porterfield was friends with Oldham; Belk was friends with Taylor; and Campbell was a friend of Gross, who was one of three people who auditioned for the role of Abby. He describes how he and his core group “felt their way” to their various roles, unafraid to take a page from what he learned making Putty Hill and toss out the script or tap into his actor’s own experience. The assemblage is something of an ideal combination of fresh faces, dramatic dexterity, inclusive generational ambit, tangible situations, and Porterfield’s light touch.

Both Holmgren and Porterfield are hard at work on the rollout for I Used to Be Darker. Porterfield recently traveled to Melbourne, Australia, and Santiago, Chile with the film, and Holmgren is working with Strand on upcoming U.S. screenings and press, as well as lining uprights for a soundtrack. While they are both eager for the film to do well, they also know its performance in the coming months could have an effect on Porterfield’s next project, Sollers Point, the final installment in a loose Baltimore trilogy with Hamilton and Putty Hill, which follows an ex-offender on house arrest. They have already turned at least some of their attention to fielding interest in the film, traveling to CineMart in Rotterdam and the Berlin Co-production Market with hopes of working with a named cast. They also plan to attend IFP’s No Borders International Co-Production Market, and Porterfield is applying for a Radcliffe Fellowship at Harvard as well as a Guggenheim Grant. The pair has raised money from the Creative Capital Foundation and Wexner Center for the Arts, and Porterfield is a finalist for the San Francisco Film Society Screenwriters Grant.

Their preparatory list of alternative financing proves Holmgren and Porterfield’s mettle, but it also underscores the hard knocks of independent production. Holmgren is optimistic about the recognition that they have already gotten for the project, but, as an advocate for creative filmmakers, you can also hear his frustration: “I don’t think it should be so hard for people like Matt or Marie [Losier], or anybody I work with…” But this is where Holmgren stops and re-focuses on his own potential to assist in this small corner of the film world. Holmgren’s determination is only second to his resolve to be positive about his own capabilities to help with the work that he so obviously cares about. In a world where press and marketers alike seem to be vying for popular approval, the largest explosion, or the best superhero, Holmgren’s efforts foreground the far more precious brass tacks of what we might see on screen—away from the multiplexes.