Julio César Morales

On June 19, 1867, Emperor Maximilian stood with Generals Miramón and Mejía before a firing squad. Maximilian’s last words were, “I forgive everyone, and I ask everyone to forgive me. May my blood which is about to be shed, be for the good of the country. ¡Viva México, viva la independencia!” The rifles erupted with smoke and fire, and the three fell.

Maximilian’s brief, tragic rule of Mexico (1864 to 1867) is understood best through his most intimate and trusting relationship: the one with his imperial chef and confidant, a Hungarian man known as Tudos. The bloody end of Maximilian’s reign yielded numerous conspiracy stories: he was ushered out of the country after his Freemasons brethren faked his death; he bribed the firing squad with gold to aim at his heart; he wore the 41.94-carat diamond that bears his name to tempt or mock his executioners. Maximilian exists in the popular imagination as a victim of Napoleon’s rule and as the subject (mid-execution) of Manet’s famed series of paintings. According to some, Maximilian dies at the hands of Tudos, who accompanies him by carriage to the execution site and, at Maximilian’s request, kills him before they reach their destination. In the famed photographs, it is Tudos who is executed. In an alternative history, Maximilian is saved by his Mason brother Benito Juárez and taken to El Salvador where he lives out the rest of his life as a noble writer Justo Armas (translates to “just guns”).

Maximillian and Tudos’s influence on the modern cuisine in Latin America was extraordinary. They created the bolillo or pan frances, which is the first ingredient in a Caesar’s salad. Forget the fancy crostini, corn bread, rye, dill, seaweed, or za’atar croutons, a bolillo was originally used to make the aromatic, toasted, fluffy squares of delight that we love to crunch into.

The biggest gift that Mexico has given the world, besides tequila (never mind the hipsters with their Mezcal or Sotol fantasies), is Caesar’s salad. While many creation stories exist about Caesar’s salad, this one was passed on to me by my grandfather, Daniel Dueñas; he should know— he was in the kitchen when it was born. During the first wave of migration to Tijuana, he brought his family to the border city from Guadalajara, Jalisco. In the late 1920s during Prohibition in the US, the southwest border with Mexico began to expand from tiny ranches to cities and “wet entertainment” was on offer for American tourists. Dubbed as a “sin city,” Tijuana developed, with the help of a very young Wayne McAllister, a plethora of Moorish- and Art Deco-styled casinos, hotels, and bars. As Don Daniel would tell me, it seemed like a city of the future. No other border cities in Mexico had the sophistication of design or were as guided by style as these haunts frequented by the stars of 1920s Hollywood.

During this time, my grandfather owned a small jewelry store and often sold his goods on a street corner, as he preferred being out and talking to people. He got to know everyone on Avenida Revolución, the main drag where all the bars and restaurants were located.

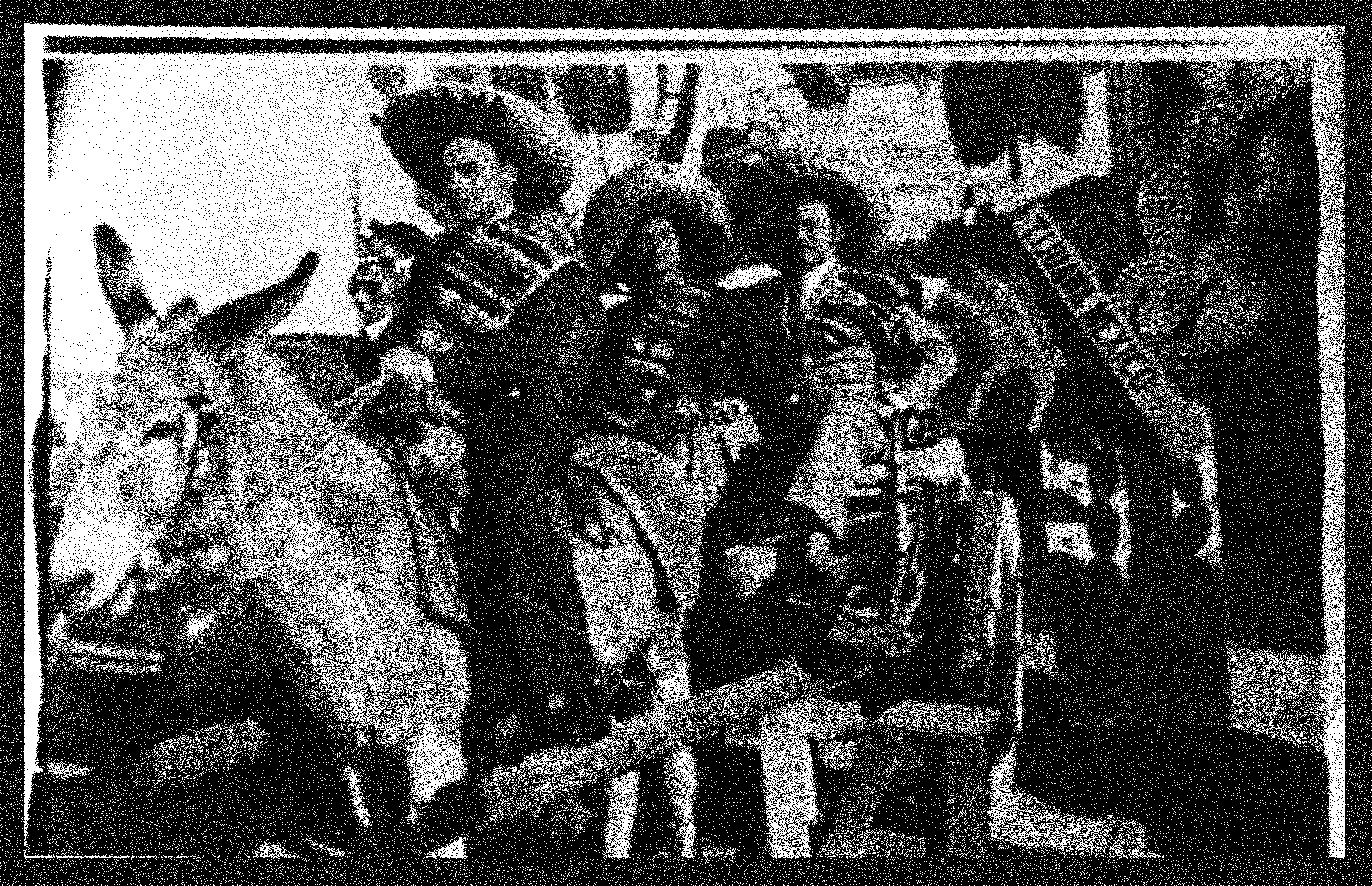

Later, in the mid 1990s while the drug cartels were scaring away tourists, I was a student at the San Francisco Art Institute and interviewed my grandfather about the history of Tijuana. These sound recordings were endless and filled with comical, sometimes tragic stories about daily street life: from his friend Antonio painting donkeys with shoe polish to make them look like zebras for tourist photo booths, to the night he met Al Capone and helped invent Caesar’s salad.

Don Daniel gave me this 4-by-5-inch photograph of him, his brother, and Al Capone sitting on a donkey. He recalled how a friend of his was La Guardarropa (the coat attendant) at Club Unicornio across the street. One night he tipped her 5 dollars to bring Capone to the famous Caesar’s restaurant. This was also one of my grandfather’s favorite street corners to vend his goods, so when La Guardarropa came over with Capone and his posse, introductions were made and the group quickly entered Caesar’s from the side kitchen entrance to meet the chef, Beatriz—a friend of La Guardarropa’s and recent immigrant to Tijuana.

As they stood at the kitchen door, La Guardarropa asked Chef Beatriz to make something special for Mr. Capone. Around the same time, it came to the attention of the restaurant owner, Mr. Cardini, that the famous American gangster was in his kitchen. He quickly came in with a tall pitcher of Martinis to welcome everyone. Over many boozy cocktails, and getting quite hungry, they started contributing ideas for a new dish in cool repose to the hot summer day. Beatriz brought out the Romaine lettuce, Capone eyed the cheese, and someone suggested salty anchovies and garlic as a paste. It is uncertain, other than an attempt to make an aioli, where the egg and olive oil comes in. According to Don Daniel, he often went to Caesar’s for chorizo and potato tortas and recalled that the cast iron skillets were coated in the delicious residue of chorizo and oil. This surface is where Beatriz warmed the open-faced bolillo, soaking in the flavors and imparting her signature mark on the croutons in this recipe.

In other versions of the story, leftovers and day-old bread are casually thrown into the salad recipe, but, on the contrary, this was a deliberate and collaborative response to a specific moment. A recipe born like an exquisite corpse drawing. Don Daniel thought it should contain the green olives from the martini drinks and Capone suggested canned artichokes…(OK, I’m getting ahead of myself, there’s a bit more story before the recipe).

This recipe is far different and brighter than you can ever imagine a Caesar’s salad to be, and YES—I am writing Caesar’s with an apostrophe because that is how it was spelled originally. Similarly, pozole is referred to by US gringo chefs and restaurants as “posole”—and that is messed up! What is wrong with the letter z and, for that matter, pronouncing words correctly? My hairs stand on end when I hear Bobby Flay say taquitos in a Boston accent. If you’re going to claim something, learn how to say it, cabron! Respected American chefs and food writers such as Rick Bayless and Diana Kennedy have spent decades cultivating and conserving “authentic” Mexican cuisine for the masses in a very respectful manner. But according to contemporary Mexican chef Gabriela Cámara of Contramar (Mexico City) and Cala (San Francisco), even her recipes are adapted according to her personal taste and skills. In a recent New York Times interview, Cámara attests that she does not claim an “authentic Mexican cookbook,” rather one that is authentic to her own experience. After all, Tijuana is barely recognized as “Mexico” by most Mexicans—it’s a border city, a third space that is perfect for invention out of necessity. In this case, a salad is improvised by a band of outsiders and becomes legend.