Interviewed by Shawn Reed

Shawn Reed: From afar, Equiknoxx seems a bit mysterious. Who is Equiknoxx?

Gavin “Gavsborg” Blair: It’s pretty straightforward. It started as a group of four in high school.

Reed: How long ago was that?

Jordan “Time Cow” Chung: Millions of years ago. (laughs)

Gavsborg: Around 2000. Three went their way… One was left, which was me. Then that one linked up with another one and then he went his way, right? Then there was one left, which was me. (laughs) Another one came, we linked up then two others came along, then they left. One—that was me, the other one was Bobby the Blackbird, and then shortly after that we met Jordan (Time Cow). Adding to that we have Shanique Marie and Kemikal, so it’s more or less like three people doing production.

Reed: Are Shanique Marie and Kemikal vocalists?

Gavsborg: Yuh, but it goes deeper than that. A lot of things get inspired with them in mind. It’s not like they’re just session vocalists, they’re part of the family. They might not have pushed a button, but that button would not have been pushed if it wasn’t for them.

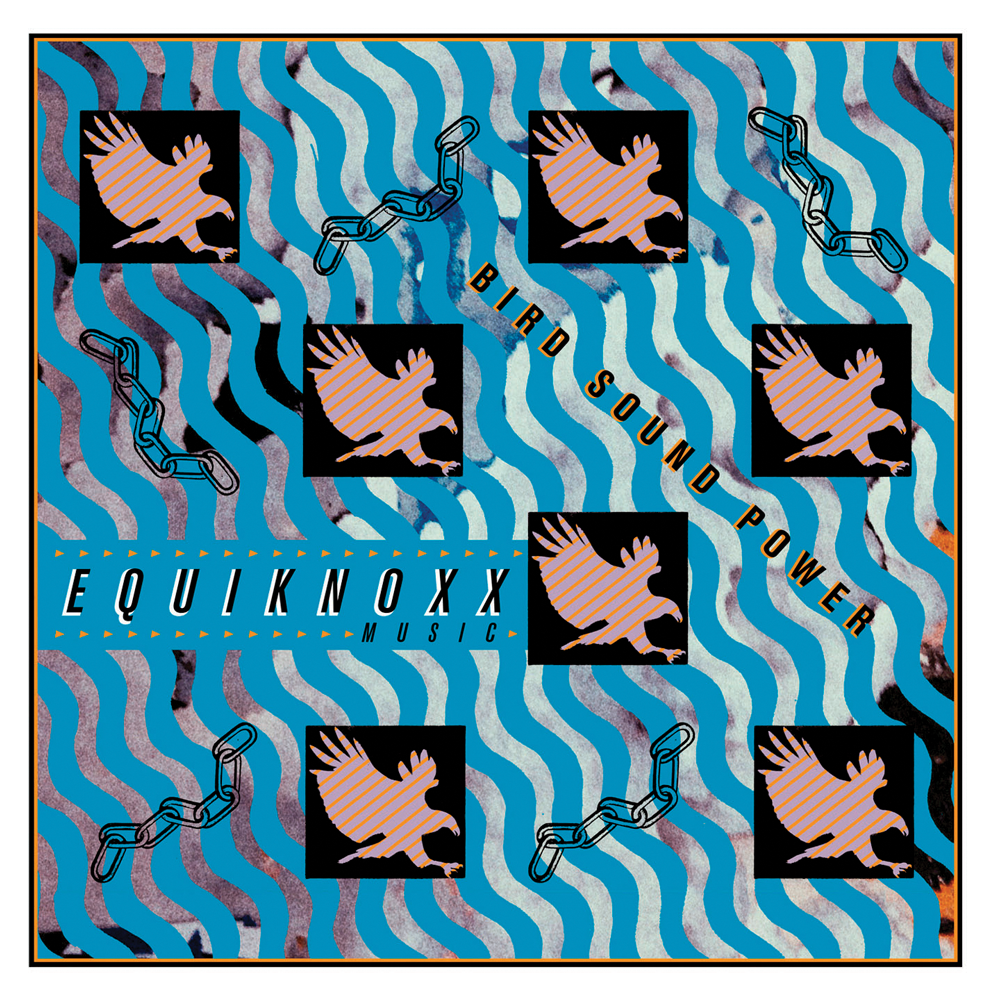

Reed: A lot of people became aware of Equiknoxx through the record that came out last year, Bird Sound Power. I think of the album as an instrumental record, but I still hear the presence of voice, or vocals, in those instrumentals. Maybe that’s one part of the process that gives the record its subtlety and depth, even though it’s quite minimal at times. I have a background in experimental music and a passion for collecting Dancehall, Reggae and Dub, so when I first heard the album, it felt like music I’d been waiting to hear. It seemed like an entirely new dialogue. Do you think about it that way at all?

Gavsborg: Nuh, nah really. It’s not like we became “weird” last year. We’ve always been different. Even in Jamaica we are known as the producer’s producer. If an artist is very lyrical, has a keen ear, and wants to express himself with something that complements him, we would be the number one stop in that regard. So artists like Aidonia, Masicka or Kabaka Pyramid, anybody who is very lyrical, it’s almost a given that they would want to work with us. We’ve always been in this kind of niche. When the record came out, it opened us up to the world, but not to the diaspora.

Reed: So the diaspora is the Jamaican, Caribbean, and West Indian communities that left the Islands and still actively imports and exports culture from back home?

Gavsborg: Right, and to the diaspora we were always the “Yo, dem man dem different.”

Reed: That wasn’t a conscious decision. You aren’t trying to be weird or avant-garde or experimental?

Gavsborg: Nah, we aren’t trying to be.

Time Cow: We’re just into being ourselves.

Gavsborg: Yeah, which is Jamaican. I’ve said this before, it’s just whether someone taps into it or not and I think once you live in Jamaica you have this mixture of space. If you just look at the history of Jamaica and the amount of people who have passed through there over the last 400–500 years: Tainos, Spanish, Africans, British, Indians, Chinese. They all carried something there. Jamaica is pretty small, so when you are born in a space like that, everything just mixes up.

Reed: It’s an island so it’s isolated and that helps cultivate a unique mixture of sound.

Gavsborg: Yeah, but I find that in a way a lot of people actually try to move away from this. But maybe after us, more people will start embracing it. Generally, Jamaicans are pretty weird people, we aren’t one-dimensional. Everyone is special in their own right, but in terms of the Jamaican approach to music, it’s actually pretty weird. A lot of people have tried hard to step away from that because to them, there is no gain. The average Jamaican can’t see that there is someone in Berlin who’s digging this stuff. People like what they can touch and what they can touch is like a weekly Dancehall, where they don’t necessarily want weird. They just want what is popular already. So now you have this Jamaican pop sound, which is seen as the most practical thing.

Reed: Has this always been the case?

Gavsborg: Always, always. A lot of people outside Jamaica have this impression that back in the ’70s it was Deep or all Dub. That’s bullshit, it’s always been this way. What was happening then was a lot of export. That’s what happened to our album last year; we did something and it got exported to a lot of people. More or less, Jamaican people love Celine Dion-type music, even when there was a few years of Dub buzzin’ in the country. It wasn’t playing on the radio. Maybe it was playing in England on the radio, but never in Jamaica. So when you talk about someone like King Tubby, he was most famously known for the Tempo Riddim, which has nothing to do with his Dub catalog. Jamaicans now are like “King Tubby, who is that?” but everyone knows Studio One because Studio One made all those nice “I’m in love” songs.

Time Cow: We had to be introduced into the world at some point. I think the album was a really good first impression because it was curated properly.

Reed: How did the record come about?

Time Cow: The journey started with one person who introduced that person to someone else. Eventually it was like… Kingdom! We are on our way to the Kingdom now. It was a good collaborative effort from everyone who was involved including Jon K, Balraj, the Swing Ting Crew, and Sean and Miles who are Demdike Stare out of the UK.

Reed: Is Demdike categorized as leftfield or experimental?

Time Cow: I’d say they have experimental production as a part of their catalogue. They’re definitely leftfield.

Gavsborg: So check this, before our music was coming out in the diaspora, if it was being played in London, it would be in Brixton or someplace where you have a lot West Indians living. So you have the diaspora, the people that are in the middle and then you have the people that are on the left.

Reed: The genres of music are classified as left, middle, and right. On the left you have experimental or avant-garde music, the right is more straightforward mainstream music, then the middle is a crossover between the two.

Gavsborg: Right, so then you have someone in the middle listening to the diaspora actively and listening to the people on the left actively. So that’s like DJ Samrai of Swing Ting and he’s hearing it in all these dances and is like “what is this?” It’s in the dance, but it sounds different. Then he says to the guy on the left “there is something over there in the dance that kinda sounds leftfield.”

Reed: In the UK you have this whole world of music that evolved out of that, and over time it has spawned other genres of music like Drum and Bass, UK Garage, Dub Step and Grime, but the roots of the diaspora are still there. It’s similar in NYC, in Bed Stuy, Crown Heights, certain parts of the Bronx, and in Queens. There are a lot of former Jamaican label people, musicians, artists living there.

Time Cow: The reason you don’t hear more experimental or different sounds in Dancehall is because it’s a lot like the mainstream music business, but it’s also really “bully” and its magnified in Jamaica. Dancehall business is a big bully, man, it’s very rough.

Reed: In what way?

Time Cow: In every way…

Gavsborg: You might get beat up. (laughs)

Reed: Has anyone talked about Bird Sound Power as a Dub record? Like say, in the same historical way that Scientist records were put together and packaged as dub albums?

Gavsborg: Yeah, some people see it as a continuation, like a 2017 update.

Reed: Does that bother you at all?

Gavsborg: Nah, not at all. It’s an honor.

Reed: Over the past year, Equiknoxx has been performing and touring in the UK and Europe extensively and it seems like a lot more touring is on the horizon. Have you enjoyed that experience?

Gavsborg: It’s been cool. Generally, we are in two scenes, sometimes even three scenes. Sometimes we play for the diaspora, which is one scene. Sometimes it’s more in the middle, like here in New York with Mixpak, and sometimes it’s the leftfield.

Time Cow: It’s cool. This last tour was live shows, doing a live interpretation of the album. Some shows are just straight DJ or bashment parties.

Gavsborg: But we keep it real. If we have to play a bashment session, we don’t just play like straight Beenie Man tunes. We do it in a way that is still us.

Time Cow: I like bashment. (laughs)

Reed: What do you like about it?

Time Cow: The energy. 120bpm to 140bpm is just pure dancing tune and grinding tune and daggering tune.

Reed: When you go back into the studio does the fun you have doing bashment DJ sessions feed back into the process?

Gavsborg: You have to consider it because, let’s just be real, you make music and you want people to hear it and you want people to enjoy it. But I think one mistake some people make is they want everyone to enjoy it.

Reed: It seems like being true to yourselves has worked out considering the variety of positive attention you have received. Equiknoxx has been around and evolving for some time now, is it surprising to have this increase in attention and opportunities?

Time Cow: It’s part of the course.

Gavsborg: Yes, it’s part of the course. I’ve been seeing my name on the billboard since I was 19, and at that time it felt good. But now it feels like we can touch it, it feels special now. Before it felt successful, but not special. The music itself was special, but it wasn’t until 2013 that we felt like we could touch it.

Reed: So Time Cow, Gavin had been working on Equiknoxx for some time, how did you link up and become part of Equiknoxx?

Time Cow: MSN messenger. (laughs)

Reed: You heard Equiknoxx productions and felt a connection and just tried to get in touch?

Time Cow: Yeah, when Gavin did Aidonia’s song, “Bolt Action,” those kind of tunes, I felt like I was seeing a new invention. It was an aha moment because music had been so shit for a while. From 1999–2002 there was a transformation period where almost all music was shit. I didn’t know what to listen to. Then Gavin put out some stuff and I was like, “WOW!” After that I said, “I have to know him.” His sound influenced my sound from scratch. Then I was in University one day walking along and I saw this strange character walking down the corridor. I just kind of ran out and assaulted him and said “you are Gavin!”… and it just went from there.

Reed: Did you have a musical background in your family?

Time Cow: Yeah, all of my uncles are active DJs, my grandfather had a sound system. I started fooling around with it and it just came naturally to me. When I was maybe 14, I found this studio near my high school and I would go in the evening after school. I started making riddims up there and around age 15 I recorded some tunes and put them out through the local radio station. That is where I was introduced to a little piece of the bullying in Dancehall music in general. You know, sometimes you have to go around and pick up some friends to get the music played.

Reed: What does Equiknoxx have on the horizon?

Gavsborg: We have some ideas, but we haven’t finalized anything yet.

Reed: Sometimes when an artist gets some success they jump into it really hard and maybe fall short of delivering quality in a way that they did before the success.

Gavsborg: Yeah, it’s not the way. You have to know when to strike.

Time Cow: It’s a game of chess… (laughs).