Interviewed by Sara Cluggish

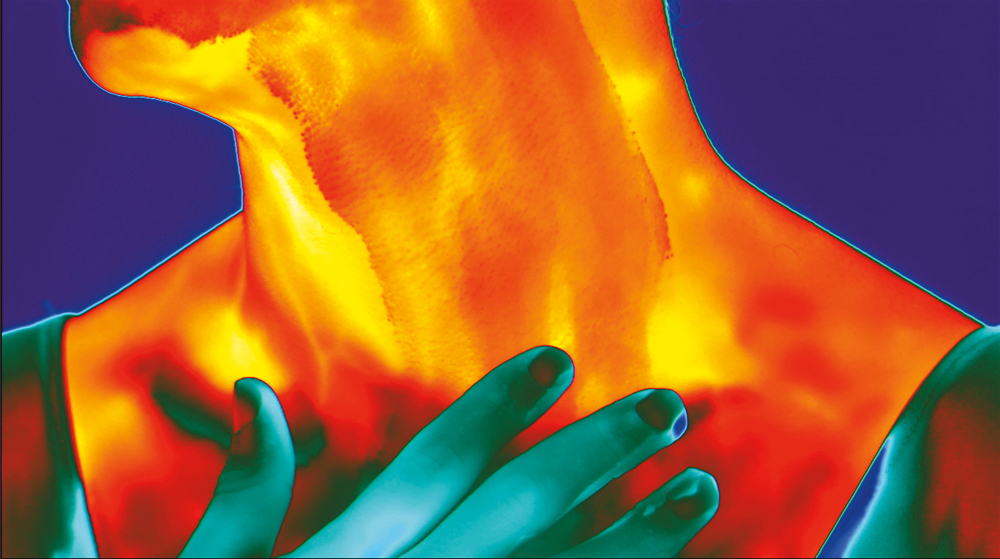

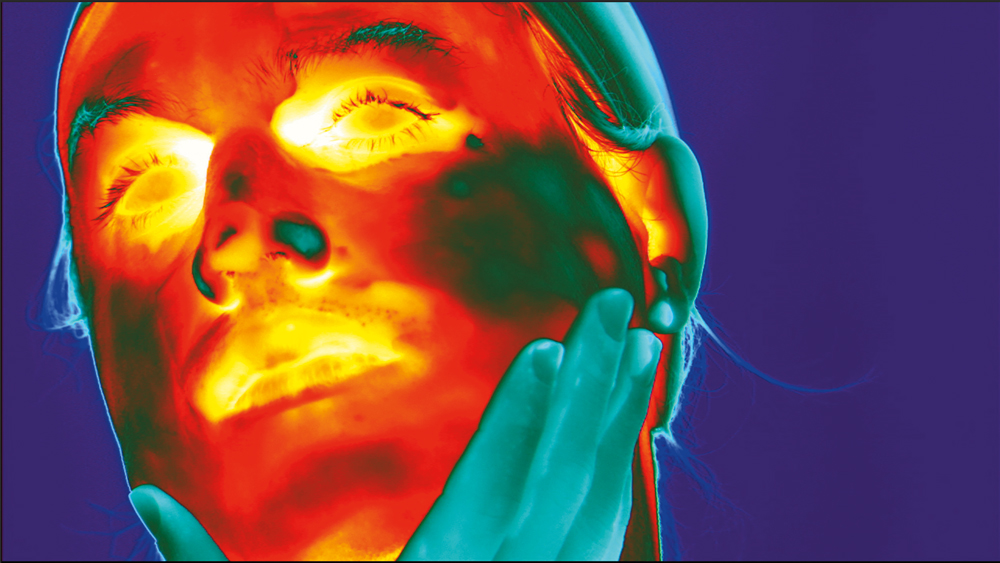

Patrick Staff, Weed Killer, video stills, 2017.

Sara Cluggish: Your most recent work, Weed Killer (2017), produced for your solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, departs from Catherine Lord’s memoir The Summer of Her Baldness (University of Texas Press, 2004). The book is an irreverent, visceral account of the author’s experiences of cancer and chemotherapy. Can you speak about illness and health as themes that reoccur throughout your work?

Patrick Staff: When talking about issues of sickness and health I often feel there is an above deck and a below deck. I could give you the more above deck, respectable narrative that traces the logic of my work, the way my research has traveled and how I read the text. Then there is the below deck version where I talk about my body, the people I know who have died, my relationship with Catherine Lord and the intimacy it involves. I am constantly grappling with which version of events to give. It feels sometimes like one version always delegitimizes the other. Those two realities constantly crash into each other. This is the method by which my videos, installations and performances are made. On the one hand, I have been producing work for a number of years about bodies, the queer body, debility, ability and labor. Questions of what is a good body and what is a bad body are consistently present. How do these questions shift amongst different groups of people? My 2013 project Scaffold See Scaffold at The Showroom in London became, over time, about disability and the place where dance and disability intersect.

Cluggish: Let’s talk about Scaffold See Scaffold.

Staff: The Showroom’s projects are often long-term, research-led commissions. At the time the gallery initially approached me, I was feeling frustrated. I felt a sense of complicity in my practice, primarily around the dance work that I was producing then. At this same time, London was coming out of the 2012 Summer Olympics, and with all of the large infrastructure projects that entailed, austerity politics was hard and fast around us. This contributed to an environment where individuals were being cut off from their living benefits and told they had to go back to work after living with disabilities their whole adult lives. I began to feel I could not keep presenting dance work without speaking more explicitly to the political context around me. Through Scaffold See Scaffold, I wanted to deconstruct my relationship to dance and performance within the gallery. I had become regularly involved in working with a small group of dancers and choreographers, who were all brilliant in their own right, but I was very attuned to the fact that they were trained dancers. They brought different histories of dance, post-modern or pedestrian dance, and, while they were not all necessarily high ballerinas, it felt hard for me to move in that direction. I began by working with this group of dancers, as well as bringing in new individuals to form a little assemblage—we called ourselves a Physical Study Group.

Cluggish: That is a lovely name. Can you speak more about who was involved and what The Physical Study Group led to?

Staff: There was a fluctuating cast of characters, but artists Cara Tolmie and Conal McStravick were the other two core members. The Physical Study Group was comprised of many different people working with performance. Alongside this, I started the meet monthly with Opening Doors London, a group of elderly LGBT people, mostly over 65, who had all been dancers in their professional lives. We would talk about what dance meant and how they felt about their bodies—almost all considered themselves disabled. Oftentimes, we would spend an hour speaking and hour dancing free form with no real structure. I would loosely lead our discussions, showing documentation of a dance work like Yvonne Rainer’s Hand Movie (1966); they would argue about why it was or wasn’t dance and then we would dance together. I also began working with DreamArts, a children’s theater in the same neighborhood as The Showroom (Opening Doors London, the elderly LGBT group, is also based in this same area). The youth theater members were all highly trained and used to a certain environment, so funnily, I had to do a lot of unlearning and re-structuring of how they performed.

Cluggish: How old were they?

Staff: Around 10 to 13 years old, and they really wanted the structure of learning a song or a dance, whereas I would start with a song or a dance and completely pull it apart. All of this activity—with the youth theater group, the elders and Physical Research Group—was taking place concurrently for the whole of 2013. As the outcome of my project, I ended up proposing that we close the inside of The Showroom’s gallery and mount a series of large-scale billboards on the outside. These contained an interview between someone I had worked with a lot throughout the project and myself. She was also a close friend of mine, and someone who formerly worked in the art world at a major London museum. She had, this always feels like a crass way of describing it, but she had become disabled. She developed an illness that caused her to stop working and to begin claiming disability benefits. Our interview starts with me asking “Do you self identify as disabled”? From there, we begin to deconstruct what I would call the different realms of disability—the social model, medical model and legal model.

Cluggish: What is her answer?

Staff: She says, essentially, “I do not wake up in the morning and think of myself as disabled.” Her diagnosis is unconfirmed by her doctor because the illness is considered speculative. Doctors do not quite know what is wrong. Medically her status is unclear, but legally and governmentally she is very much disabled. We begin by speaking about the three positions of how she thinks of herself, how her doctor sees her and how the government views her, going deeper from there. She and I are so close that throughout the interview she naturally begins to ask me questions, largely about my gender identity. The conversation stops being strictly me interviewing her and gets a bit fuzzy.

Cluggish: I read these billboards a number of times and so much of the dialogue is really about intimacy, down to the informal, open way you chose to edit the text. I have been thinking in my own research about illness or disability existing in a place that is deeply personal but also highly bureaucratic, and, for me, Scaffold See Scaffold speaks so effectively to this tension. I suppose any visit to the doctor, without even delving into a highly nuanced conversation around benefits and the legal system, is to some extent a vulnerable experience. Doctors and patients enter into an exchange that hinges on trust and honesty, but also extremely clear communication and detailed record keeping.

Staff: Yes, absolutely. The majority of people who look at the intersection of transness and disability politics are talking about this exact thing, the kinship of pathologization or the kinship of bureaucracy imposing itself on an intensely personal bodily discourse.

Cluggish: It becomes about control and agency.

Staff: Yes, and it was through Scaffold See Scaffold that I was first knitting all of these ideas together in a way that felt quite personal. We also held public readings of the interview where anyone was free to attend, but a different group involved in the project facilitated each reading. One event was led by the elderly LGBT group, another by an LGBT dance group, another by a group of choreographers that I worked with regularly and one was led by Sisters of Frida, a disabled women’s cooperative and activist group I was in dialogue with throughout the project. Naturally, each group of people led the conversation in a vastly different way, bringing their own priorities. Yet, inevitably the discussion would turn back to the fact that we were standing on the pavement outside of the gallery reading aloud in the street. What did we look like as a group of people? With Sisters of Frida, the group is mainly composed of disabled women who are wheelchair users. This made for a hugely different conversation to one led by a group of young, able-bodied choreographers, each of whom bring a different agenda when reading the interview.

Cluggish: Why did you choose to host the discussions outside of the gallery? Why mount the interview on the exterior of The Showroom’s building?

Staff: I wanted to force the viewer, the audience, to be accountable in the process. To enter the gallery and engage with the text felt too much like it was letting the audience off the hook. Putting the interview on the exterior of the building was a response to a particular climate in the United Kingdom. The woman in the interview talks at one point about cutting people’s hair in her living room and having to keep it a secret because her disability benefit was not enough to live off of. If she told the government that directly she would lose her benefits, so to broadcast this context on the street as opposed to displaying it inside the threshold of the gallery felt incredibly charged, highly politicized. It still would today. From Scaffold See Scaffold I tumbled straight into my next piece, The Foundation (2015), a long-term video project made at a commune in east Los Angeles, which is also the Tom of Finland Foundation and erotic art archive. These two works are almost as different as chalk and cheese in their appearance, yet, in my mind, are intimately linked. I shifted gears and began making The Foundation, but the questions of Scaffold See Scaffold still lingered. What is the good body? What is the bad body? Where do they belong? How do performance and gesture manifest themselves? The Foundation really became about my presence within a group of men who live in the Tom of Finland house, as well as a very particular archive of a very particular type of male body.

Cluggish: So in both of these works there is a gradual, below deck exposure of your relationship to content which becomes central to the making of each piece. That exposure might come through a particular line of questioning in an interview or through the heightened awareness of your relationship to the Tom of Finland house and archive.

Staff: Yes, absolutely. You are right in the sense that The Foundation ostensibly began as a video portrait of a community, and became a portrait of myself in that community.

Cluggish: The Foundation is also haunted by Tom of Finland, an artist who made a considerable impact on masculine representation and imagery in post-war gay culture, and who is now deceased. On a level, the work is a memorial to Tom of Finland. Can you describe the house and resultant video for those who have not seen it?

Staff: The Foundation is a 30- minute, large-scale video installation that begins as a documentary portrait of the community who live in the Tom of Finland Foundation. The actual building is a large, wooden, slightly craftsman-ish, typical L.A. house. It is made unique in that it is home to the group of men who bought it in the 1970s as a commune for the leather community. At this time the leather scene coalesced in neighborhoods like Echo Park and Silverlake in east L.A. This is where all the leather bars were, for example.

Cluggish: Does that same scene still exist today?

Staff: Yes, but it has become more relegated. There are one or two bars and the Tom house that keep it going. At one point, Hyperion Avenue had so many gay bars on it, but today you would never know that. I ended up visiting the house in 2012 on a friend’s recommendation. I had been making work about communes, collectives and groups of people who would come together in resistance to capitalism or industrialization, often in a historical European context; this included anarchists, nudists, the resurgence of the back-to-land movement after the 2008 financial crisis and even a resurgence of interest in witchcraft. When a friend recommended I visit the Tom house, I did not even fully realize that it was a commune.

Cluggish: What was your impression when you first walked up to the house?

Staff: I arrived thinking it was going to be a modernist building with white gloves and a receptionist who would say, “Leave your backpack here. What materials do you want to see? These are the rules about reproduction.”

Cluggish: “Pencils only, no pens allowed!”

Staff: Yes!! Literally, there was a group of middle-aged, leather bike motor guys on the porch smoking cigarettes. Durk Dehner, who I would come to learn is the head of the whole operation, came out in a boiler suit and said, “Hi. What are you doing here?” I ended up having the most incredible tour of that house. It was immediately striking that there was no hierarchy for Durk. He showed me the archive, his office, the bedrooms, kitchen, a fully functioning leather dungeon and then we went outside to the garden. For him, all of these spaces were of equal importance, and I was so struck by that. I was also struck by the fact that I could not tell who worked there and who lived there, who was on payroll and who was volunteering. Someone’s bags were in the hallway, and when I asked about them Durk told me there was a kid who got thrown out of his home because his parents found out he is a drag queen. They let him move in so he could get back on his feet. She ended up transitioning and is still around the house a lot.

Cluggish: Is the house a place a lot of young people seek out? Do people make a pilgrimage of sorts there?

Staff: It can be, yes. The scene that gravitates around it is queerer with a certain amount of trans or transmasculine people. You do not quite find the men that Tom’s drawings depict. I ended up seized by a desire to make a film with them or even to spend time working there. But, at that point in 2012, I was in quite an intense moment of gender crisis and self-questioning. I was wondering whether I would transition formally and medically from male to female, but I was very much presenting as a gay man and traveling through the world in that way. There was a moment when I became aware that my reception in that space, their generosity and welcome, felt potentially predicated on an identity that they only perceived me to be. I wanted to spend more time there, but I worried that if I broke that thread of trust, if I told them I am not actually sure I was who they perceived me to be, my access would be revoked. In this way, the entire project ended up being about the complexity of my identity as a younger, transfeminine person trying to figure out how to negotiate my relationship to an older generation of men, all of which is mediated by the building and the archive.

Cluggish: Do you feel you received answers or a sense of resolution through making the work?

Staff: Maybe not answers, but there was a certain amount of closure. We all worked through something together in the making of the work.

Cluggish: The word intergenerational is often foregrounded in relation to your work. Why is the specific nature of intergenerational dialogue so generative for you? Does this way of relating naturally tap into a personal sense of history and cull that history forward?

Staff: Back when I was at art school almost everything I was interested in fell under the banner of appropriation and reproduction. I was obsessed with the New Narrative Movement, with post-structural ways of approaching identity and writing, such as Chris Kraus’ Native Agents Semiotext(e) series (2006). In a way my practice today has ended up becoming a funny sort of bastardized version of this early interest in appropriation and the deployment of personal identity into a broader political context, but the cross-generational dialogues have naturally happened. The works I was making were always very discourse heavy, by which I mean the exhibitions and work I made became vehicles to enable actual conversation.

Cluggish: I think there is also a certain personality-type that naturally values mentorship. It is interesting to me that when I bring up the term intergenerational you go back to the mental space of being a student. This is a formative time when cross-generational exchange becomes especially important. Also, as you were talking, I began thinking about the importance of Catherine Lord’s memoir The Summer of Her Baldness to your most recent work Weed Killer. Could we think of this text, or any memoir really, as its own kind of intergenerational exchange? A dialogue between writer and reader that is not confined by time. I also wonder why you are so drawn to the confessional genre of memoir?

Staff: I think this interest is born of dissatisfaction with the archive. When I was more regularly making work that would refer into the archive, I was always trying to poke at archival material and agitate it so as to get a response. Now, that desire has shifted to living people that I can agitate. (laughs) Think about my two most recent works, The Foundation and Weed Killer. Neither are easy exercises in intergenerational relationships. There is reverence for Tom and Catherine in my work, but the videos are not necessarily loving portraits.

Cluggish: Both of these works are, in different ways, wrestling with grief.

Staff: Yes, absolutely. Around the time that I began making The Foundation, I was also coming out of a very complicated experience with a mentor that ended badly. It was with someone of that same generation of men who live at the Tom of Finland house. For me, this complication was very present in the work. In the foreground, there are questions about my identity and the identities of the men at the foundation, which constantly collide and trouble each other. Then in the background there are questions about grief, sickness, and care for a body. There is a moment in the video where the men at the house are caring for Tom’s images of bodies. I am entering the space as a younger person trying to understand what my responsibility is in this context. Is there a sense of cultural inheritance? Am I meant to carry the torch? Is my relationship to these men familial or more exchange based? All of these anxieties about caring and intergenerationality are present.

Cluggish: While we are still on the topic of intergenerationality, can you speak about the choreographic sequence in the second half of The Foundation which takes place between yourself and an older, male performer? There seems to be a lot of mirroring between the two of you, which holds particular significance.

Staff: There are a few different things to talk about. I had been making a lot of dance work, thinking a lot about pedestrian dance or very simple stylized gestures as a language in choreography.

Cluggish: But then the music is so captivating, the kind of tune that your body cannot help but respond to.

Staff: Totally. The music is actually taken from a porn film that I found in the archive at the Tom of Finland Foundation. Francis Lee, the actor performing, and I move incredibly slowly rather than the music affecting a more energetic response. The whole thing becomes an exercise in juxtapositions.

Patrick Staff, The Foundation, video stills, 2015.

Cluggish: The last time I watched The Foundation, I thought that the scene almost feels like watching an intimate, two-person exercise class. Some of the movements are like lunges and you are moving in tandem, as in Tai Chi. To push this analogy further, it becomes impossible to tell who is the teacher and who is the student.

Staff: Right. The choreography is about creating confusion between who is the leader who is the follower, or it being unclear which body is meant to be doing it right, so to speak, and which is doing it wrong. My hips have a fluidity that Francis’s do not. There are certain moments of strength where my skinnier arms do not quite hold up in the way that Francis’s do. In its simplest form, my choreography is a strange pas de deux that I produced by stealing or appropriating small movements from various places and stringing them together.

Cluggish: From where, for instance?

Staff: I was watching a lot of Japanese theater when I made The Foundation. I would put on Noh theater videos when working in my studio because the format is long and slow. There is very sparse percussion and chanting that indicates a change in mood or scene. Actually, the percussive sounds in The Foundation draw heavily on this. I also love the use of stylized gesture and the restrained ways emotion is shown in Noh, whether this is through the use of masks or through simple movement.

Cluggish: I can see the influence of restrained facial expression in many of your works.

Staff: Yes, there is a moment of Francis and I looking backwards and forwards at each other. We are looking into the camera, but I think of it as us looking at each other with all these signifiers switching between; there is a moment where makeup comes off my face and is on his face. We start to switch outfits. The shirt that looks tight on him suddenly looks disheveled and baggy on me. Another interesting aspect of Noh Theatre is that traditionally the choreographic plays were performed by family theatre troops, and knowledge of how the play was to be enacted would be passed from father to son. I was hooked on the idea of somehow reproducing that dynamic. The scene where he is adjusting my body and trying to get me in position references a scene in a documentary about Noh Theatre where a father teaches his son the exact position for a specific pose. Additionally, I was thinking about the structure of ballet companies where one dancer is tasked with remembering the dance in their body. This individual is not necessarily the best dancer in the company, but is the person with the ability to remember it in their body most clearly. In The Foundation, Francis becomes a choreographic elder who physically embodies the Tom of Finland Foundation and house in a way that I cannot. His gestures have meaning that mine do not.

Cluggish: Throughout this conversation, in many different ways, you have referred to the context of the workshop and the group dynamics this brings as embedded in the formation of your work. At times the workshop operates as a research process and other times as an exhibition strategy.

Staff: I think nowadays this is still part of the process, but I have been foregrounding it less and less in the final presentation. In the past, I would operate from that space to generate the work and it would also become the form the work takes, what is seen.

Cluggish: Why do you think that is? Could this transition depart naturally from gravitating less towards straight performance and more towards video work over the past few years?

Staff: It is a little bit from working with video. It is a little bit from becoming more of an egotist, if that is the right term. I do not have as large of a burning desire to relegate my own authorship as I used to.

Cluggish: Why?

Staff: I don’t know if I just got it out of my system. I think it was a reaction to going to art school and a reaction to being at Goldsmiths at a very particular moment. I experienced a frustration with entering the professionalized art world that led to a desire to push back against it. I also tend to have a bit more of a laser focus now about what I am trying to get at. In a way, my most recent works, The Foundation and Weed Killer, are the least collaborative works I have ever made. In other ways, these are the most complex collaborations.

Cluggish: Do you mean intellectually? Emotionally?

Staff: I mean working with all of the individuals who live and work at the Tom of Finland Foundation, or negotiating between myself and Catherine, myself and the actors, as well as my own relationship to The Summer of Her Baldness as a text.

Cluggish: Shall we talk about your relationship to the text? How did you meet Catherine Lord?

Staff: I met Catherine Lord when I invited her to write a text in response to The Foundation. I had not read The Summer of Her Baldness at this point but I had read other works of hers, and she was someone whose writing I loved. I knew she had an intimate connection to Los Angeles and she had written a little bit about Tom of Finland, so I tracked her down and tried to woo her. I was very enamored with Catherine. She is incredibly fierce, intelligent, sharp and a little terrifying.

Cluggish: What a great description. I think at some point many of us come into contact with a person we admire who would easily fit this categorization. What did you feel when you were reading The Summer of Her Baldness? How was it generative for you?

Staff: Reading it was like being astounded by it constantly, or it being overwhelming in its brilliance. That sounds so corny!

Cluggish: Every word feels like the right word in the right place. Can you explain the idea of “Her Baldness” as a character or alter ego in the book?

Staff: Her Baldness both is and is not Catherine. This character embodies her illness. As Catherine exchanges long emails, keeping friends and family up to date with what is happening, she invents Her Baldness. In other parts of the text Catherine speaks directly to Her Baldness. It is an incredible methodology. She talks about sickness, the sick body and the semiotics of the body in ways that hit home for me without ever having experienced cancer or chemotherapy in my own body. It was compelling, and I did not necessarily know what to do with this at first.

Cluggish: You also worked with an anthropologist while making Weed Killer, correct? Why?

Staff: Yes, S. Lochlann Jain. Loch wrote another incredible book Malignant: How Cancer Becomes Us (University of California Press 2013), which is an examination of how cancer functions in American society. The opening introduction describes a future in which the economy would collapse if a cure for cancer was ever found. Loch’s argument is that culturally we have separated the cause and effect of cancer to such a degree that how cancer functions is completely tied to an obfuscation of cause and effect. In relation to this, they cycle through the functions of gender, the insurance industry, the advertising industry and the various levels of cancer’s economic behavior. Loch examines the nuances of the umbrella term of cancer, which in actuality contains many various illnesses underneath it.

Cluggish: Malignant: How Cancer Becomes Us is also partially memoir, correct?

Staff: Yes and not quite. It is not as intense a memoir as Catharine’s, but Loch is using themself as a subject to a certain extent. Loch recently gave a talk at MOCA, LA, where Weed Killer premiered, and our discussion kept cycling back to cause and effect in terms of living authentically. Questions of choice kept coming up. For instance, Loch hypothesizes in the book that it might have been fertility treatments that led to their cancer. These treatments were a result of having a child outside of a heterosexual relationship. They had IVF, artificial insemination, knowing that this choice would greatly increase their risk of cancer. But when Loch was diagnosed with cancer, there was no way to fully know if that was the cause. Yet when having conversations like this one, it is natural to fixate on cause and effect.

Cluggish: In that light, IVF seems like a huge gamble.

Staff: If you are trans and decide to take hormones this is often one of the first disclaimers given. This action hugely increases one’s risk of cancer. This is a personal choice that has to be made. Gender theorist Susan Stryker writes about how the enactment or the lived experience of different types of bodies makes a demand for a different type of society. This struck me. When developing Weed Killer, I thought a lot about how having a different type of body, whether you choose it or not, implicitly makes this demand that ripples out into the world.

Cluggish: These bodily decisions, or perhaps not decisions, begin to dictate the structure of one’s life—a structure molded through many different spheres, on many different levels.

Staff: Yes, absolutely. I went into the project of Weed Killer with my desire to re-work a section of Catherine’s book, and knew it was not going to be an easy exercise in intersectionality. There is something inherently complicated and sticky and difficult about my friendship with Catherine. I asked Catherine to adapt a section of her book but explicitly wanted to interject onto it, introducing my own subjectivity. I wanted to further shift the text into being performed by a trans actress, Debra Soshoux, inviting Debra to bring her personal subjectivity as well.

Cluggish: You were slowly mutating the text.

Staff: Exactly. There is a lot of body doubling going on—Catherine to Her Baldness, to me, to me asking Debra to perform as Catherine but also to perform as herself. In rehearsing the text, I actively encouraged Debra to think about her relationship to it. Yes she is acting, but saying a line like “Why do men own both dicks and baldness?” or even talking about the scars on her breasts means something so different coming from a trans woman than what Catherine’s original text was chipping away at. My desire was not to shy away from this, but to let the meaning shift. Let the weight of these words take on another form.

Cluggish: Why did you title the work Weed Killer?

Staff: In the opening monologue of the video, Catherine/Debra compares chemotherapy drugs directly to weed killer. The potency of these pharmaceuticals would easily fit in on the pesticide shelf. This speaks, I suppose, to my desire to needle at questions of what we think of as being medicine and what we think of as being poison. There is an incredibly complicated and fine line between the two. We go through processes of killing ourselves to be reborn. I am often deliberately treading these blurry borders in my work. What is nourishing me and is poisoning me. What is utopian is incredibly conservative at the same time.

Cluggish: We have talked about the thin boundaries between pleasure and pain.

Staff: Exactly. The mentioning of weeds becomes a very circuitous part of the monologue in the video. Catherine/Debra describes being in a therapy group and talking about compassion fatigue, which is essentially when you have an illness and the people in your life peel away. It hurts. Someone in therapy group responds, “when you are depressed, go out and weed in your garden”. Then it comes back around that as a cancer patient, you are pumping yourself full of weed killer. It creates this really porous scenario. I think often in my work, and in how I talk about my own gender, there is always this question of how much do you allow me to be me? I am often touching on this compromise or resting in this tension whether it is with a lover, a friend, a police officer or a doctor. There is always a negotiation. Why am I only as much of a woman as you allow me to be? It is as if I only have so much rope. A similar feeling comes out in reference to the group therapy session in Weed Killer, but also in the later half of the video when Jamie Crew, another trans actress, performs a song sequence to a bar full of people who ignore her.

Cluggish: It really hit me that the lyrics of “To be in Love” (by Masters at Work featuring India), are so personal but also highly repetitive, making for a kind of relentless intimacy. Jamie is desperately singingly “I am in Love” over and over and over, showing the enamored effects, but also the hurt that a deeply loving relationship can have on one’s personal psychology. It is possible to feel almost addicted to another person. Yet, amidst this confessional song, everyone in that bar is completely ignoring her performance. There is no reciprocity.

Staff: To an extent Weed Killer is about the articulation of suffering and pain. I wanted to incorporate the bar scene with Jamie to flip Debora’s monologue. In the first half of the video Debra is speaking so intensely about cancer to the audience in the gallery. She is sort of self-possessed and angry, but also has a wry, guarded sense of humor. I wanted to then contrast that with a club scene where Jamie projects extremely hard onto a group of people. Who is able to articulate pain, who receives this articulation and how?

Cluggish: You have mentioned previously that Jamie’s sequence in the bar is a reference to a Claire Denis film.

Staff: It is a reference to a scene in Claire Denis’ J’ai Pas Sommeil (1995) in which a drag queen who has just committed a terrible crime goes directly to a bar and sings “I am in Love”. The people in the bar are not quite as ambivalent in Claire Denis’ film, but they are certainly not cheering and clapping. I am interested in a certain lineage of trans people performing, this scene in particular being a transfeminine woman performing to a group of cis gay men. There is a proximity between those identities, but that solidarity, that allyship, easily collapses.

Cluggish: There are also sequences in Weed Killer in which both Jamie, Debra and yourself are shot with infrared film which gives a beautiful banded color effect. What is the aesthetic and conceptual reasoning behind this technical shift?

Staff: The cameras and overall technology we used for the thermal imaging sequences are most commonly used in hospitals as a method to detect different forms of illness including tumors, inflammation or broken bones by mapping areas of heat. Thermal imaging is also applied in an industrial context to locate malfunctioning machinery, for example, on a factory production line that might be overheating. For most people, this technology’s dominant visual language is one of surveillance. I wanted to meld these references together while also misusing the technology. I perverted it by applying thermal imaging to the arena of video, while allowing its intended use and surrounding connotations to play out. The technology shines when you point the machinery at a body. It highlights the lack of boundaries the body has. There is a porousness between the body and clothes or the machinery we interact with.

Cluggish: The thermal imaging offers a new and seductive way of reading the body. It foregrounds the body’s strangeness by showing how much is happening just under its surface. These sequences sit in stark contrast to the less otherworldly, more literal representations of Debra and Jamie.

Staff: In both The Foundation and Weed Killer, there is a subversion of the language of filmmaking which goes back to my interest in appropriation, new narrative and post-structuralism. I see filmmaking as a pre-existing form that is the dominant language of cinema, and a genre with which I can have a parasitic relationship. Both videos deal in the suggestion of documentary that undoes itself gradually.

Cluggish: In a way there are two modes of representation in each video. Loosely, the first half of each offers this suggestion of documentary—lingering, almost photographic shots of the Tom of Finland house or the re-presentation of Catherine’s text—and then each film slides into more bodily, movement-based forms of knowledge. Is this similarity in structure a conscious decision?

Staff: Whether consciously or not, I certainly always go back to the authentic image or ideas of the image you can trust, the style we all know and understand. Then, I twist a knife in this a little bit, which allows the viewer to question the authenticity of what is being shown. I want to keep people on their toes, to try and implicate the viewer in what I am making. I want to produce film that you cannot quite trust which means you stay active. I would add that this is done with a certain amount of generosity.

Cluggish: You are not being sneaky or nefarious.

Staff: No, but I do encourage agitation. Weed Killer begins with a naturalistic performance from Debra that shifts into a stylized performance from Jamie, referencing a more staged and cinematic language of filmmaking.

Cluggish: To end, can you describe To Those in Search of Immunity, the sound piece you are working on for Collective Gallery and the Edinburgh Art Festival in Scotland?

Staff: I am working on a couple of different things right now. I have been writing a text for The Serving Library in Liverpool while working on the Edinburgh piece, both of which are produced in parallel to Weed Killer. Collective Gallery has commissioned an audio piece to be listened to on headphones while walking through Canton Hill, a surrounding public park.

Cluggish: Have you made a strictly audio work before?

Staff: No, but in all my previous works, sound is incredibly important. For Weed Killer, I worked with clarinet and saxophone players to achieve a percussive, atmospheric sound by pushing these wind instruments until they sound like they are gong to break. After this experience, it has felt natural to transition to making an audio piece. Even though To Those in Search of Immunity is an audio walk, I wanted it to feel less like a tour and more like sleepwalking. Canton Hill has a number of famous historical monuments relating to Scotland’s history, maritime and astronomical traditions, including the National Monument of Scotland. This monument is essentially a Scottish version of the Parthenon, representing Edinburgh’s relationship to science and history. In the daytime this area of Canton Hill is buzzing with tourists visiting monuments, but a famous problem is that people have sex in the park at night. It used to be more of a gay cruising spot and nowadays is mostly occupied by drunk straight people coming home from a night out, stumbling into the park. To Those in Search of Immunity rests on this but begins by talking about colonialist botany and the history of moving plants around the world. Collective Gallery is situated on this hill and from it you can see out to sea. There is a lot of signaling of boats coming and going. The work references this, and the botanical, colonial expeditions in which weed species would find crafty ways of traveling with the more official plants, eventually invading the surrounding landscape. The piece shifts from talking about tourists in the daytime to people having sex amongst the weeds at night. I also talk about wetness as a conduit for knowledge. I suppose it becomes a pornographic story about being in the park at night, made for people who will be walking around in the daytime.

Cluggish: Aside from the obvious connection to weeds, and taking into account that you are finishing it as we speak, how does To Those in Search of Immunity sit within your practice at large?

Staff: There is a sense of wanting to think about the constitution and ecology of the body, as well as the porousness of these boundaries. At the same time, the writing introduces immensely complex relationships between sickness and health, sexuality and desire, to put illness and sex in hard dialogue with each other. This dynamic is softly present in Weed Killer with its weirdly desirous sense of the illness being the contamination of desire, while To Those in Search of Immunity goes after these complexities more directly.