Interviewed by Sara Roffino

Sara Roffino: It may be funny to start off talking about Richard Serra, but your video Chances (2015) has some similarities with his film Hand Catching Lead (1968).

Alina Tenser: There is an uncanny likeness there. Serra’s work has never come up as a reference for me, but I rather like that two artists of different generations and discourses came to a similar conclusion. In a way both works deal with verticality and relentless flow. But Serra’s film is concerned with endurance in a way that my video is not. In a 2001 interview with Charlie Rose he talked about following a curve and delineating inside and outside space and these ideas are important to my work as well—innies and outies, and negative space being positive. Thinking about what is negative and what is positive you start to see its dimension and rather than being about presence and absence it becomes solely about presence. For me, Chances is a very uplifting and hopeful work.

Roffino: And there’s humor in Chances too.

Tenser: Yeah, for sure, humor and gesture—and it’s not an ironic humor. It’s pretty earnest.

Roffino: Serra’s work is so physical, so much about experiencing those lines and those shapes with a body. It’s not just about looking at them, but being in them.In that Charlie Rose interview he acknowledges, albeit obliquely, his hyper-masculine reputation. Have you had to deal with a feminization of your work?

Tenser: Yes, for sure. And I don’t reject the notion that my work is feminine. I think there is great strength in the feminine, just like I think there is great strength in the domestic. But these terms feel limiting. My practice is more specific and idiosyncratic.

Roffino: Are you familiar with the inaugural exhibition at the new Hauser Wirth & Schimmel gallery in Los Angeles? It’s called Revolution the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women, 1947–2016 and includes over 50 artists—from Louise Bourgeois to Abigail DeVille. It’s an attempt at correcting the historical exclusion of women working in sculpture. Like yourself, many of the artist featured in the show also had performance as a significant part of their practice.

Tenser: I think that many people would probably agree that for a while now, the most influential sculptural work is coming from female sculptors—Isa Genzken, Rachel Harrison, and now Anicka Yi, to name a few. They have made tremendous impact and gave other artists permission stylistically and materially. Women have not had a prevalent voice, or even a voice, in the visual arts (specifically sculpture), so there is not a prominent lineage with traditional materials or means. A friend of mine, a male painter, mentioned that he often feels a lineage when he looks at old masters. He asked me what kinship I feel with Rodin or Picasso’s sculptures and I realized I don’t feel like that’s my lineage. When I see that work I have interest, but I don’t feel that we’re of the same meat. And women are responsible for bringing non-traditional materials—those of craft, those of daily life—into the conversation. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence that many female sculptors included in the Hauser, Wirth & Schimmel show include performance as a staple of their practice. This has happened in my practice as well because there’s a natural transition from the use of everyday materials to performance. An awareness of the body has also played a huge role in material choices and interest in performance.

Roffino: Are there artists with whom you do feel a lineage or a shared sense of sculpture, objects, and space?

Tenser: As far as feeling a kinship, I remember seeing Ree Mortin’s work early on in undergrad and that was meaningful. Lynda Benglis’ Spills were important for me, and a bit later, Joan Jonas. More recently I had a similar feeling when I encountered photos of Valie Export’s performances with staircases, where she conforms her body to the stairs. Currently, I am working on a collaborative performance with Chris Dominick which I’m excited about because I think we have a common approach when it comes to objects and a lot to learn from each other as far as performance.

Roffino: What is the common approach to objects?

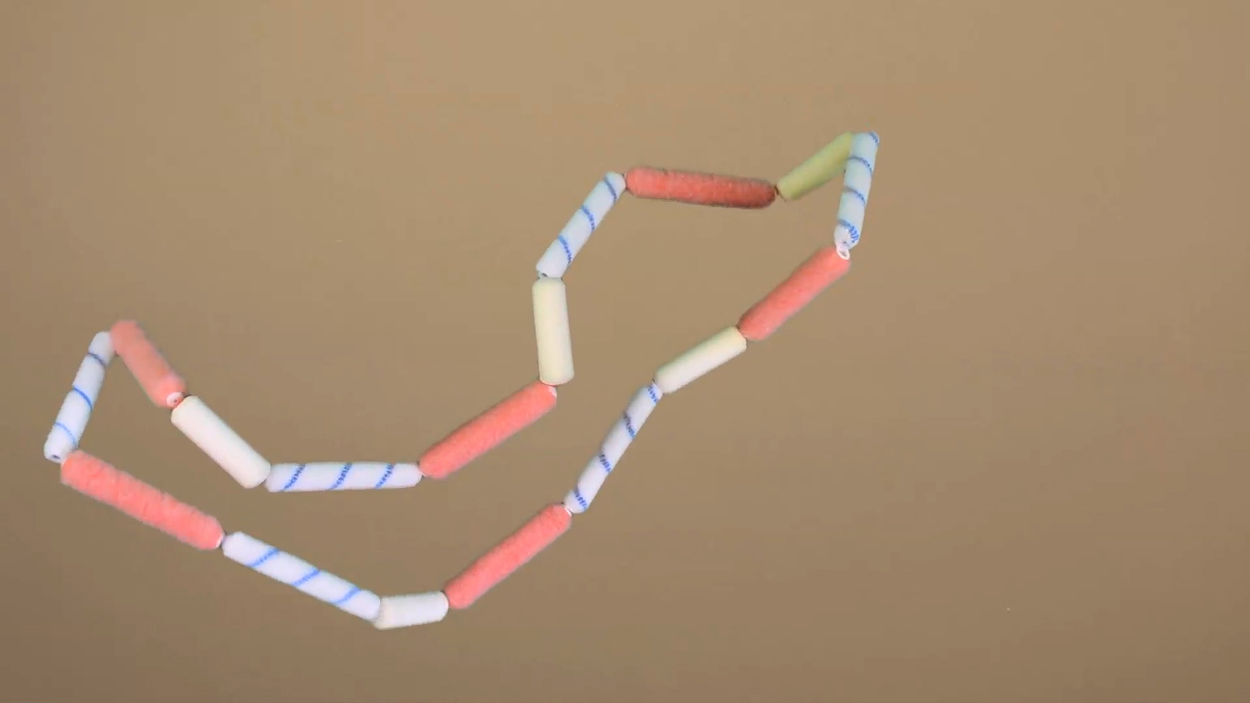

Tenser: I guess we are both interested in the way that an object narrates. I never refer to my objects as props because I feel like they’re not assisting the thing or the statement. They are the statement, which is tricky because a lot of times you make things and your movement is heavier, the animation of the object can resonate heavier than the object itself. It’s interesting to think about what is assisting what.

Roffino: Your work is so much about your engagement with the objects that you make —the performance is really about the objects too. Are you saying that regardless of your interaction with the them, the object is still—

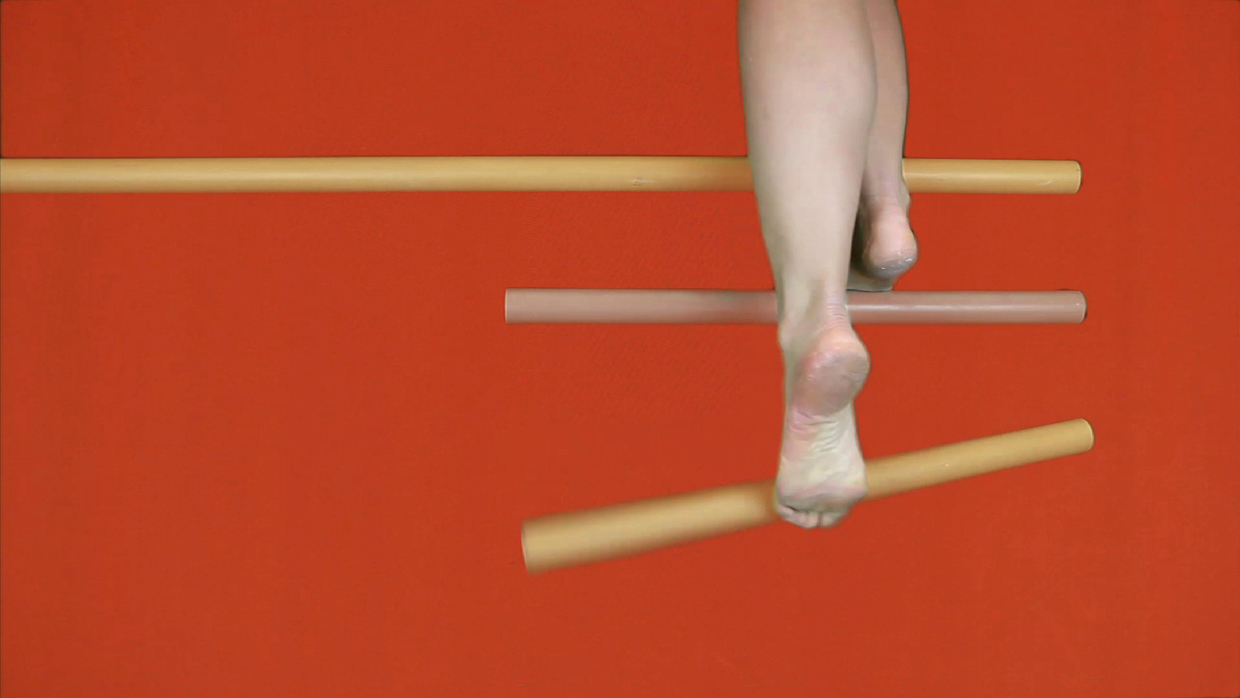

Tenser: It’s still a performative object because the way it is made is very specific to my body and the movements assigned to the object are also specific to my body. To explain better, I’ve done three performances—Vegetable be Soap (2014), Selections from Sports Closet (2015), and most recently, Transaction Stall (2015). All of them started out with a stage and once I had the stages I started moving around them and trying to figure out the movements that were conducive to the space. Once I understand the movements, the objects are conceived so the objects come after the actions. The objects form to the actions, and the actions form to the stage.

Roffino: So the stages are the starting point. Where does the conception for them begin?

Tenser: They get named pretty early on, depending on how I see their functionality. Like in Transaction Stall the language I assigned to the set was “Shower ATM.” For me it’s important that it’s not a shower and it’s not an ATM, but there’s some kind of likeness to these things. And there is a similarity between these two elements as well—both have a private stall quality that’s interesting to me. I have been thinking about ideas of public and private recently, partly because those are words that were given to me, language that Rachel Valinsky used to talk about my work and it felt relevant. The word stall kept coming up in my head, a term describing privacy, or privacy in a public space, as well as a forced slowness or suspension.

Roffino: What was the context that public and private were applied?

Tenser: Rachel was talking most obviously about my use of green screen and how much I choose to reveal. And my practice being one that is for the most part quite private, but I think that a lot of my personal life spills out in the work. In the future when I’m looking back at my work, I think it’ll be easy to tell how old my son, Nikolai, was when I made each work.

Roffino: How will you be able to tell?

Tenser: Already, when I look at works from 2011 and 2012, I see how much I was dealing with the body. I was really engrossed in this idea of the body being a formless blob, or the body as you experience it from within, rather than the figurative body. This is when he was an infant and young toddler; pregnancy and birth were also still fresh with me. Looking at how the work has progressed, currently there are a lot of influences from ideas about early childhood development education and educational programming, Like games, logic, magic, and even small feats of physical conquering, like balancing and things like that. Which kind of corresponds to him being 6 years old.

Roffino: Something that becomes really apparent in the Hauser Wirth & Schimmel show is how many of these artists use performance as part of their sculptural practice. This is your trajectory as well. What is it that performance can do for sculpture?

Tenser: Performance really expands on sculptural strengths because it can identify the body as it stands with or interacts with an object in a way that is really about making. When I’m holding my work I feel like the maker, and when I’m performing with my work it’s actually very enjoyable because I know so well how to handle it, I have the tactile knowledge of making it. And I think it’s kind of a richer experience of knowing a form.

Roffino: You also employ video and projection as sculpture.

Tenser: Yes, but with video I feel like it’s a much more formally driven way of knowing a form and knowing an object because it’s almost like it becomes the platonic ladle or the platonic bucket— in that they are disconnected from the maker, from their material, and from their instability in time—rather than the vessel that you water plants with or something. The first videos I made, which I just call Video Reliefs, are videos of my hands touching a sculpture. That was how I showed that sculpture. Slowly I started making longer videos that were kind of scripted and more edited and with last year’s show at the Kitchen, I brought the screen out into space. I realized that it was a sculpture with a kind of video surface.

Roffino: The videos are of three-dimensional sculpture compressed back into two dimensions.

Tenser: Yeah, and it also has something to do with time and compressing time because I feel like time isn’t present in my videos. In performance you can always kind of see the start and the end. You can understand the material coming into its form and becoming an object. In video that never comes up. Again, it’s about this platonic thing that exists mysteriously and infinitely and has life that is autonomous from the maker.

Roffino: What was the process of finding performance within sculpture?

Tenser: In 2012–2013 I had a residency at Recess. I spent that time trying to do something and it wasn’t happening. I was trying to achieve a fluidity between object making and video making, but I couldn’t escape the notion that one would end up being the product. I was making objects for the camera, but I wasn’t making props or light stand-ins for something real. I was looking at dimensions and functions through a camera and making formal decisions about how the object would look. The first thing I did was build a stage that was on wheels, and then I made a video of the stage and I thought the camera would be on the stage and I would start shooting video from the stage. But I just couldn’t make that jump so the work didn’t progress until I started working on the performance Vegetable be Soap in 2014. Finally there was fluidity—a fluidity within uncertainty appeared naturally. One really formative thing that did happen at Recess was that I was paired up with a writer, Jillian Yung. Her research was focused on performance and early video work. This was fantastic for me because this was where I was trying to aim my work, but I had little understanding of it. I have always used language to direct my work. For example, during my time at Recess I was making these stretched fabric pieces that stood in space and I was calling them screens and video stills. And the videos of objects I was referring to as sculptures. Both were a total stretch, but it helped me aim the work where I wanted it to go. Now my videos are projected on very specific screens that stand in space and are talked about sculpturally. So playing with language, and just simply acquiring language from Jillian for what I was trying to do, was a really important foundation for what I’m doing now. Roffino: What was it about performance and working on Vegetable be Soap that helped you find the fluidity?

Tenser: While I was working on the performance I was really uncertain about where my logic was coming from, but I trusted the visceral urges I had for using specific objects, like an oversized wooden ladle and a photo reflector. The stage changed quite a bit from when I first conceived this performance. It became elevated and angled so that when I laid down on the set (which is how the performance takes place) the viewer just saw my feet. I worked on the set, the performative objects, and my choreography simultaneously, and I modified them in relation to each other.

Roffino: And you’ve been thinking about your work in terms of screens for a few years now. I’ve always thought of the screens in your work as analog screens, but there’s clearly another layer there, right, like screens as in screen culture?

Tenser: I always want the screen to be something to look at and then something to look through because screens really do function in both ways, even the screens on which I’m projecting video. The more recent screens are freestanding and there’s some space on the bottom or the top where the plexi is just clear. I want the screen to be a considered object where there is a double focus—focused on, and focused through. But screen culture comes up so often that I feel like I have to go there. I feel like as much as I insist on language and develop language, I’ve also really have to hear other people’s language because it’s proved really insightful in the long run. I don’t necessarily relate to the pop-up screen, multiple screens, the sort of screens we see in Trisha Baga’s work, for example, which I like. But the virtual screen is definitely very interesting.

Roffino: So when you’re using screens in performance are you thinking also about the screen outside of its ubiquity in screen culture?

Tenser: I guess I recognize it as such, but I rarely treat it that way. There has been some kind of a screen in each one of my performances. This nods to my use of green screen and the screens that I project videos on. In Transaction Stall, there’s a screen that addresses the virtual screen more directly. I use a shower curtain, which is a type of screen, that is patterned with small triangular cutouts. I was thinking of the triangular icons on a desktop window used to adjust the size of the windows. Thinking about screen culture is not at the forefront of my practice, but I know that the reason I was thinking of this pattern is because I had this imagery of windows you pull out. And the language of it, screen and window, I really enjoy. It’s really kind of progressive—it’s about portals and transcending.

Roffino: Transcending what?

Tenser: Surface, material, dimension.