Interviewed by Mary Lodu

Mary Lodu: Could you tell me about your involvement with the group WSABAL?

Michele Wallace: I founded WSABAL in 1970, when I was 18 years old. It stands for Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation and it developed under my mother’s direction and prompting and support. It has a complicated name, which is something people were doing back then, making up names or acronyms like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) or whatever. In this case my idea was to found a black feminist art organization, but I knew there weren’t that many black women who were interested in feminism. Trying to get them together on anything was like trying to herd cats. So I named it WSABAL because it meant that you didn’t have to be black; you didn’t have to be a woman; and you could be a student. I mean it was simply for black art liberation. So that was myself and my mother [artist Faith Ringgold] and whoever else we could round up at the time — a daring band of people. My mother kept it going for many years, through correspondence.

I’m now much more interested in the things I did in the 70s than I was for many years. For instance, when I wrote my first book, Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1978), I don’t even mention WSABAL. I don’t mention any of the art activism I was engaged in with my mother. I now think that it was all very important in building myself up to write that book; my book was born in that tutelage in art. In the process of writing it I came to understand that being involved with WSABAL was not the thing that would get my book published and that would get me an audience and make me a writer. Our founding principle was to address the issue of exclusion, and a major issue for me in particular from then until now was the exclusion of my mother’s work. In the beginning, when we were involved in the Art Workers Coalition and protesting at the Whitney, it was about the exclusion of black artists. Then the black male artists went behind the curtains and made various deals for themselves, and when it emerged that that was taking place, it turned my mother into a feminist. It turned me into a feminist. So that’s when we began to fly the flag of WSABAL and to collaborate with other feminists. All women activists were trying to work with the men and invariably they radicalized us.

Lodu: So WSABAL challenged the exclusion of black women from white and male dominated art establishments while also responding to how black male artists disregarded black female artists?

Wallace: Yeah, but the thing that gave us the power was that white women were being treated the same way. So ultimately we were able to work together. Unfortunately, despite the exclusion of black women by black men, black women were not as ready yet to work with white women or with themselves, and so you get black feminism really emerging more in the 1980s and again in the 90s and even now.

Lodu: The WSABAL Manifesto makes it quite clear that the group’s primary interests were grounded in black feminist values. It voices a number of concerns and demands regarding various forms of racial and gender oppression experienced by black women in the visual arts in such an unprecedented way that it anticipates the frustrations openly expressed in your controversial text, Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman. How was the Manifesto initially received? Was it met with any resistance from members of the Art Workers Coalition (AWC) or the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC)?

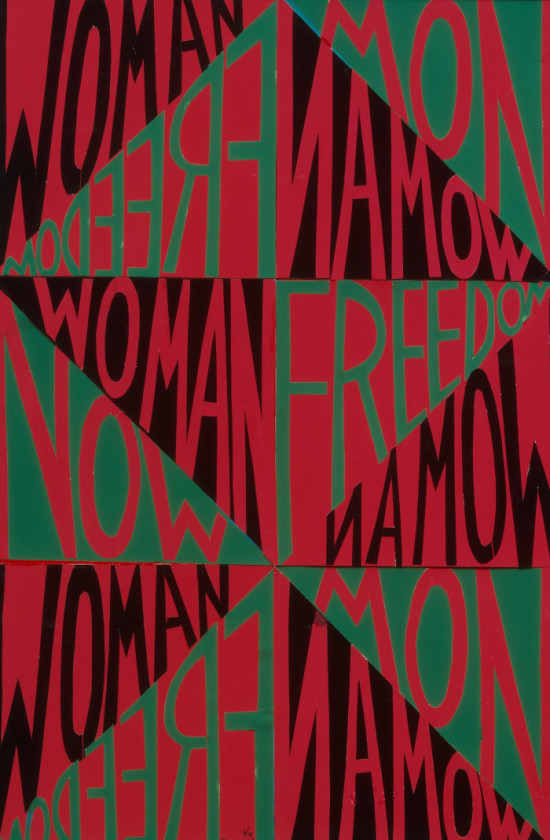

Wallace: Absolutely, absolutely. In fact, I think people thought I was crazy, or that my mother was crazy. WSABAL statements were frequently not signed because, first of all, you wanted people to think the group is big, but there was also something about the times in that people didn’t sign their names to things. For instance, when my mother did that flag show, I helped with the design for the poster. She may have created the design but I wrote the words.

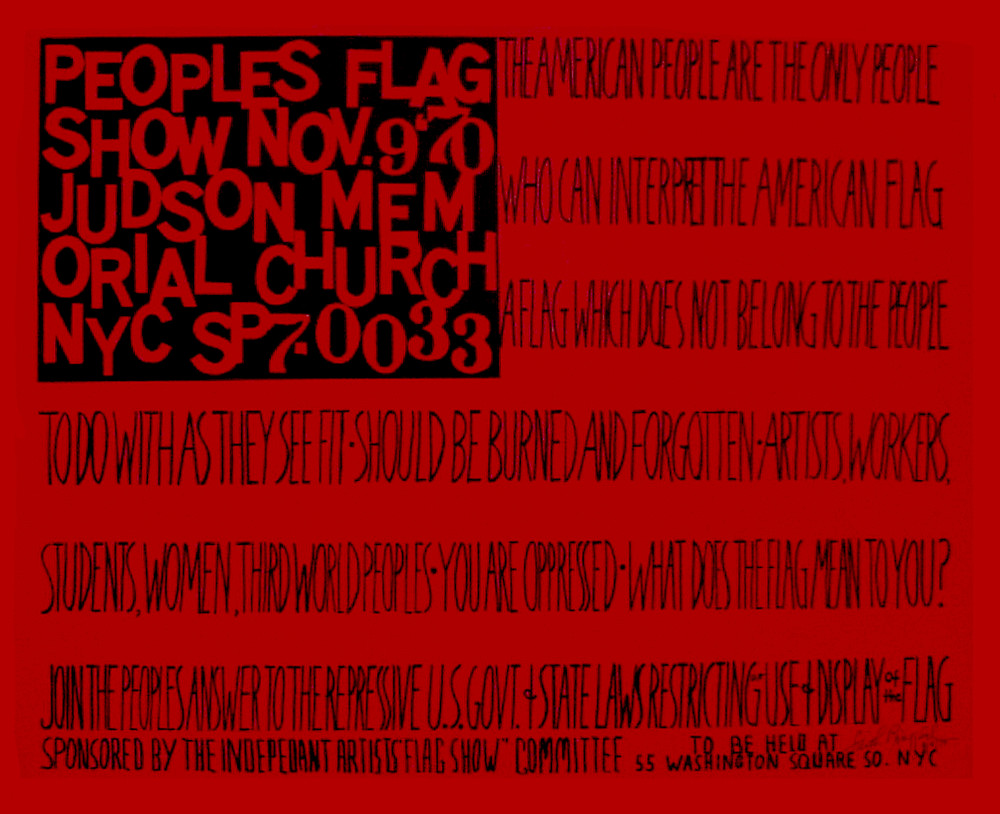

Lodu: You were involved in the People’s Flag Show where your mother was arrested? Can you speak more about that?

Wallace: It’s on my mind, because my mother just spoke about it at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and she has frequently told the story about how officers from the Attorney General came to the People’s Flag Show at Judson Memorial Church in 1970 and arrested me and John Hendricks for organizing the show. She came upstairs to get me and I said, I can’t go. She said Why? Then I said, ’Cause I’m under arrest. One of the undercover policemen said that I was under arrest because I was one of the organizers of the exhibition, but then my mother said that she was, in place of me. Truth be told, I wasn’t necessarily involved because I was still 18, I was young, but I will never forget sitting there with Jean Toche, John Hendricks, my mother, and trying to figure out what was going to happen. A lot of other people were involved as well, but somebody had to do the grunt work. I wrote the text for the flag. It’s kind of incendiary, although it’s her design and it sells for a lot of money today. (laughs) The thing is, it was very awkward and uncomfortable because one minute I was under arrest, then the next minute my mother was instead; it was awful and I’ll never forget it. She took off her rings and gave me the keys and I was instructed by them to go and call everybody and contact all the lawyers and, you know, I also had the task of telling my grandmother about the arrest. It was just horrible. It would have been horrible, I suppose, if it was me who was arrested, but it also made her arrest illegal because essentially they traded her, she traded herself for me, and you’re not supposed to be able to do that. It seems their instructions were to get one black woman and two white men.

Lodu: So since you were involved in organizing the event and also contributed text to your mother’s poster, was the The People’s Flag Show a WSABAL action?

Wallace: Yeah it was WSABAL action.

Lodu: Because I haven’t seen that noted in writing about the exhibition.

Wallace: It was WSABAL no matter what we did. And you know, John Hendricks, John Toche, everybody had lots of names for organizations they had. If you were there founding it and saw the people, you understood who was involved and how it all worked. Anyone could join Art Workers Coalition, but a lot of the men in the group resisted feminist values and beliefs. As for BECC (Black Emergency Cultural Coalition), one of the things that I learned by reading Susan Cahan’s book, Mounting Frustration: The Art Museum in the Age of Black Power, and by organizing the tribute for Norman Lewis for my mother’s foundation this summer, is that Norman Lewis, Romare Bearden and the group Spiral were also involved in the protests against the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 1969 exhibition Harlem On My Mind. I think that’s how the BECC started. From there I learned a lot about protests at the Whitney. Different groups had different techniques. Now it seems like the BECC was less radical and wild. There were points when people made demands to close shows or to be disruptive and BECC never led that kind of disruption; it was more “civil rightsy.” The way Susan Cahan describes it, BECC was a slight departure from Spiral, and Spiral didn’t protest anything, really.

Lodu: I’m glad that you bring up Spiral because I recall reading in your mother’s autobiography that Romare Bearden denied her entry to the group, which Norman Lewis was also a member of.

Wallace: Yeah, Norman was in Spiral, but I can see now that he wasn’t treated like a full member, even though Romare Bearden was his good friend. There’s a picture you can find in Susan Cahan’s book with him wearing a placard outside of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the placard says “Mighty white of you Thomas Hoving,” or something like that. Now I can’t imagine Romare Bearden wearing such a placard — as a matter of fact, we know he would not have. Bearden had his rough edges but doing stuff that might compromise his reception wasn’t one of them. This was a protest against Harlem On My Mind. What then followed inside is that they had a panel discussion debating about whether or not there’s such a thing as Black Art, obviously for the purpose of future inclusion to the Metropolitan’s exhibitions and collections. All the players were on it.

Richard Hunt was on that panel, who is one of the people who ended up having a show at MoMA because of our protests, and also Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, William T. Williams, Richard Mayhew, Benny Andrews, and I forget who else. But about this discussion on whether or not there was such a thing as Black art, one of the things that stands out is how uncomfortable they all were with the idea of art being particularly African American or Black. I think every single one of them said there was no such thing. They said Harlem On My Mind was not okay because it was an exhibit about Black people at a museum that had never had a show of African American art. They wanted to have that show, but they didn’t want it to be called “African American” artists because they themselves didn’t want to be labeled as such. They varied in the ways they said it.

Lodu: So Bearden, Lawrence, Andrews, etc. are the black male artists you were referring to in the WSABAL Manifesto whenever you mentioned “Black token art” or artists “copying Whitey”?

Wallace: Exactly, exactly. That was me reading and responding to their lingo and I think we had a particular dislike for Benny Andrews (laughs). I mean it all seems very stupid to me now but the fact of the matter is reading Cahan’s book and getting the record and seeing what people were saying and doing, I began to realize that my take on everything at 18 and 19 was largely based on discussions I was having with my mother. Now I can see that everybody really had a different technique and this I will share with you. In each case the technique was about getting their work in the museum, in the galleries, and sold, and that included my mother as well, everybody who was yelling and screaming and protesting. Some people thought that art was dead, the art world was dead, that everything to do with the galleries and museums was a total rip off. A lot of people felt like the art world had been kidnapped by racism and sexism and the forces of war and evil. Then there were artists like Frank Stella whose work had nothing to do with politics, but they were contributing to these protests. So that was one way; another way was my mother’s. She was making wonderful art, but nobody would look at it and she couldn’t sell it. Nothing was happening for her. So there was no point in staying in her house and filling it up with more paintings. She was out there trying to create a world that would be receptive and interested in her work. She was willing to go as far as she needed to make that happen, but didn’t really make that happen. It ended up causing her to be completely ostracized by the financial mechanisms of the art world. Howardena Pindell called it…

Lodu: Howardena Pindell wrote a critical essay providing statistical evidence on racism in the art world in the 1980s, I believe?

Wallace: She nailed it, and at the time she was working at the Whitney as a curator. Ten years after all of this, she told the whole story exactly as it was.

Lodu: Other actions led by WSABAL include the Liberated Venice Biennale and protests at the Whitney Museum in collaboration with the Ad Hoc Committee. Both groups picketed the Whitney Annual in 1970 [the Annual became the Biennial in 1973], demanding the inclusion of women and black artists. Could you talk about those experiences? Especially how the latter resulted in Betye Saar and Barbara Chase-Riboud becoming the first African-American women artists exhibited at the Whitney. I’ve often felt that these efforts have not received enough recognition in writing on the Feminist Art Movement.

Wallace: I’d love to talk about that because there were women who tried to fight us from Art Strike (AS) on the Liberated Venice Biennale but they quickly turned because there were all kinds of things going on. I mean people were breaking up, there was lots of craziness. It was “peace and love, not war,” you know? But the women who were all in business with each other split over the idea of women artists being included in the exhibit. Lucy Lippard was a key person in the movement, she led the revolution. Lucy, my mother and I, we all became advocates, we had a great time. But what is it we were working on? We were working on protesting the Whitney Annual and the next Annual was supposed to include sculpture. In the final analysis, after all the funny things like throwing eggs at people, blowing whistles, and other goofy actions that happened, it came down to well, who do you suggest? For us it was to suggest some black women sculptors. There was probably a list, so the two they chose were Betye Saar and Barbara Chase-Riboud, neither of whom has in any way acknowledged or accepted the fact that they were the beneficiaries of this effort; both of whom epitomized non-black feminist values in many ways, as people. But for a long time whenever we would walk in any of these museums, the employees would call security. The guards would surround us because they’d think we were trying to start a demonstration of some sort. That stuff we did back in the day — I wouldn’t try that today! Museums are like fortresses now! I think we may have seriously affected the architecture and layout of these spaces.

Lodu: I wouldn’t be surprised.

Wallace: It was really wild then and people were really eager to see our demonstrations, you know? Performance art as part of what they come to a museum to have. But they never, I mean never called the actual police. Now the museums have so much security, and they’re all black men, right?

So with BECC I think I’ve explained some of my hostilities toward it. They were a very male-dominated group and were only interested in male artists and peaceful demonstrations in order to get people into shows. I see now they were very effective at it. As Cahan documents, there were a number of shows that came out of that moment and wouldn’t have if they’d been angry, and, you know, yelling and disturbing the peace. But actually Norman Lewis’ sign was the most disruptive sign I saw, and who was it that didn’t really seem to get the most out of it? Norman Lewis. He made wonderful art and I cannot understand the degree to which his work has been neglected. It was actually during this period that this brilliant man applied for a New York hack license because he could not support himself despite all the beautiful paintings he had been doing for years. He was that combination of an abstractionist with a radical political past. Like his buddy Ad Reinhardt. He turned to making abstract art, the one thing black people were not allowed to engage in was abstract art. If you were white male, it was the ticket.

I remember a colleague of mine mentioned that Linda Nochlin had written a new book, a sort of greatest hits titled Women Artists: The Linda Nochlin Reader (2015). So I got out my kindle and got the book. I looked at the table of contents to see what, if anything, she had written about black women artists. And the answer is almost nothing. It’s a book that is inclined to confirm this idea that there were no black women at all in the discussion of feminist art. It’s divided by decade, the 70s, 80s, and 90s and she’s got brief mentions on Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro. In terms of black women the biggest menton is of Kara Walker. I think it has to do with rotating, like back then people wanted Betye Saar and Barbara Chase-Riboud because they were in galleries, so now it’s Kara Walker. Black artists are interchangeable, really. They are kept at the margins and not considered substantive in any way. It’s as if they haven’t made any contributions in the activism and in the work. We can replace each other and I’m very disappointed in Linda Nochlin for that. On the other hand she mentions meeting with Lucy Lippard at a demonstration one time. I don’t think of her as an activist, she was more the academic side of it and her field is 18th century French art, so she would not be strong in regards to contemporary art and what feminists were doing as artists. But she is famous for her essay, “Why Are There No Great Women Artists?”, which basically kickstarted the field of feminist art criticism, god help us, which could scarcely be more lily white. It’s not very surprising but it speaks to your question about not getting credit.

Lodu: You also interviewed your mother for the first issue of the Feminist Art Journal in 1972 about a commission she completed for the New York Women’s House of Detention, a prison that remains associated with feminist icons like Angela Davis, Dorothy Day, and Andrea Dworkin, who were all incarcerated there. In that conversation with your mother you talked about gender roles, prison reform, rehabilitation, and how this project of hers led to the forming of Art Without Walls. Can you tell me about your mother’s painting, For The Women’s House, and how this relates to the forming of the group Art Without Walls?

Wallace: I like that you found a connection between all of this, because yes, Art Without Walls was a group we helped to form. We got thrown out of the prison once, on account of a former friend who decided she was gonna sneak in a copy of The Black Panther Newspaper. But I mean the whole thing pales in comparison to what it’s come to today. This was after Attica so there was a lot of interest in the art world in bringing art to prisons, and once again Benny Andrews was part of the male contingent that went into the men’s prison. As far as I know, our group was the only group that went into the women’s prison. It’s very sad that things have grown worse, so much worse. I just saw a report about Attica, a new book about Attica — it’s one of those situations that has not been at all improved by time or activism.

Lodu: It’s interesting because one of the largest national prison strikes is occurring right now.

Wallace: Where?

Lodu: All across the nation! It began on September 9th, the anniversary of the Attica Uprisings. There’s a lot happening right now as far as prison reform and/or prison abolition is concerned.

Wallace: It’s true that I only listen to NPR for 15 minutes in the morning when I wake. I heard something about the anniversary of the Attica uprisings but I don’t like when I’m not getting any news about what’s happening now, because I know what that means. It seems that it’s possible for all sorts of things to go on in the prison and there’s no light shed on it whatsoever. I mean people seem more capable of ignoring things; we wouldn’t do that then.

Lodu: So what happened to your mom’s painting?

Wallace: There’s a whole terrible saga about that painting being taken away from the women and put somewhere in the men’s prison. I understand that, once again, it’s in the basement somewhere. The Brooklyn Museum is doing a show on women and art activism in the 70s and they are in the process of borrowing it. I think at this point we really have to concentrate on keeping it out of the prison because it doesn’t seem to stay with the women, it keeps getting removed. Some people came to my mother’s garden party, former guards and retired guards, and warned her that the painting was in danger again. Of course once you take it off the wall and put it in the basement, it’s just a hop and skip away from the dump.

Lodu: Didn’t the Women’s House of Detention close in 1974?

Wallace: Oh yeah, the painting was never there. It went to Rikers Island instead. You see the whole of Rikers Island is a major prison complex, one of the biggest and one of the most violent in the world. It’s total chaos because, to my understanding, most of the people there haven’t been convicted, they’re just being held without bail.

Lodu: I recently read Angela Davis’s book, Are Prisons Obsolete?, which was incredibly eye-opening for me. It exposes so much about the history of imprisonment and the relationships between slavery, capitalism and the prison industrial complex.

Wallace: Davis is mainly interested in abolishing prisons, which is essentially like abolishing slavery. In other words, the abolition movement is to the far left.

Lodu: That sort of leads to my next question because WSABAL coincides with the formation of the collective Where We At: Black Women Artists, Inc. And then there was also another organization you co-founded with your mother and several others, National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO), which essentially locates you within a legacy of second-wave black feminist activity. How does this influence your perspective of liberation struggles and political activism today? The newly formed group, Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter (BWA BLM) is one example of a recent development in arts activism that seeks to address challenges relevant to our current political climate.

Wallace: My mother helped start Where We At.

Lodu: Were you involved with that too?

Wallace: I was around but the problem is Where We At was a totally different group; it wasn’t a feminist group and at some point we parted ways because those women didn’t want anything to do with white women. It was a very black-centered group.

Lodu: Wasn’t it a component of the Black Arts Movement?

Wallace: Exactly. My mother was somewhat aligned with their views but not entirely, and NBFO, yes we helped form that. Absolutely. But now I want to address this because when you first told me about BWA for BLM, I hadn’t heard of them, so I looked them up and from what I can see, it kind of reminds me of Where We At in the sense that it was mainly black women supporting black men.

Lodu: You mean as far as Black Lives Matter is concerned?

Wallace: Well, from what I understand, black women started BLM but we never really get to talking about what’s happening to black women even though as far as I know, black women are catching as much hell as the men are. Somehow we never focus on those issues, police brutality against women or women in prisons, because if you have it all tied up to the men, the men are always going to be the most important.

Lodu: That’s been a recurring issue in discussions around gendered state violence. Police brutality involving male victims always takes precedence.

Wallace: Exactly. I was really surprised to see BWA for BLM but we still have a long way to go. I keep thinking that I will not live to see black visual art accepted as a significant part of the legacy of African Americans and the thing that convinces me of that more than ever is this Museum of History and Culture

Lodu: The Smithsonian?

Wallace: That does it. It’s a slavery museum. (laughs) We don’t need a slavery museum! There’s so much African American art at the Smithsonian but there seems to be no signs that they’re really focusing on the work itself. I knew they were gonna do the slavery thing, it’s understandable. But why have people relive the experience of our trauma? Meanwhile every achievement we’ve made in sports, music, and dance will be paraded before we ever get to fully appreciating African American art, and I don’t know what that’s about. What keeps us from this? What prevents this? What holds this fact in place?

Lodu: Recent proof of this can be found in an article from 2015 by Randy Kennedy in The New York Times titled, “Black Artists and the March Into the Museum.” There was absolutely no mention of Faith Ringgold, despite all her work with WSABAL, AWC, and BECC in challenging exclusionary practices within art museums. What are your thoughts on such erasure?

Wallace: He just decided he was going to do what needed to be done to announce that this stuff was financially “here.” It doesn’t include Faith Ringgold, it doesn’t point out in any way that there is a political aspect to it. Luckily for me and my mother, she’s strong right now, especially with MoMA having bought Die (1967) and having it displayed in the museum’s collection. The Museum of African American History and Culture, they want the politics and African American art associated with political urgency. And yet that’s the reason why Mr Kennedy didn’t want to include her.

Lodu: There’s definitely a strong tie between Faith’s political activism and her art practice.

Wallace: Damned if you do, damned if you don’t, she has all of that and more. She’s essential to the people, she’s all over the topic of slavery, she’s all over the issue of prisons, you can’t get around her. But Kennedy, he’s nakedly interested in the financial benefits; his point is look, this stuff is selling for millions so pay attention, and then he throws Betye and Alison in there so you can’t say he didn’t include any women and now as far as I’m concerned he’s asleep at the wheel. That recent piece on James Kerry Marshall seals the deal. I think he’s a functionary. But. I’m glad I’m 64 and not 18 because I have a much more philosophical approach about these things. (laughs)

Lodu: Yeah, I was certainly bothered by that but what also baffles me is that Faith was omitted from A History of African American Art (1993) by Romare Bearden.

Wallace: Yeah he excluded himself too. You know, he was trying to keep the standard high. He wanted to prove he was a classy black male. He wanted to be taken serious, there’s actually some useful stuff in that book. The thing is, she felt she should be included among the first ranks from 1963, when she was 33 years old, whereas Romare was 20 years older than her. It’s a different generation and she was upset by their rejection of her, as she wrote in her autobiography. Have you read her autobiography?

Lodu: I’ve read portions of it.

Wallace: I think it’s in the nature of artists; in order to be a visual artist you have to seriously believe you should be number one, and if not, you should probably find something else. So she felt that way, Romare felt that way, they all felt that way. There was a woman in the group Spiral and that was Emma Amos. She was one of Hale Woodruff’s students. So what did that turn out to mean? Not much.

Lodu: I’ve wondered why Emma was the only woman accepted into Spiral.

Wallace: Because Emma was Woodruff’s student and they needed a woman who couldn’t have possibly benefited from it at all. Emma ended up becoming a total feminist and nobody in my view is more excluded now, even though her work is amazing. Howardena Pindell also; both women who started on the inside. With women it’s terrible because you just have to get old. As Louise Bourgeois said, the art world loves young men and old women. Bourgeois is a name you wouldn’t have known if she had died at 50. I can see the ways in which there are problems with women in the art world, period, and they carry over to black women as well, even much worse. It’s just extraordinary when I consider my mother being included in MoMA’s collection, the women included, women who are accepted now but weren’t accepted then, like Lee Krasner and Elaine De Kooning and to see Alice Neel, who they treated like shit. Louise was beginning to be accepted but she was very angry because she was very old. My mother has a little bit of that too. Because why do you have to be in your 80s to gain recognition?

Lodu: So how are Black women artists to contend with this?

Wallace: Well I counter it by writing about women. One thing I’ve realized recently is that people are not interested in what I have to say about my mom, and they probably aren’t ever going to be. I mean that’s why I wanted to do this interview. Anyone who comes to me about WSABAL or Faith goes to the top of the list, because that’s how rare it is. And I think it’s going to get even rarer now that she’s more successful, but that’s okay because the point was to get her in the game, and she’s in. But the game remains the same whether you’re in it or out of it—the game has not changed, and that pisses me off.