Interviewed by Jonathan Thomas

Jonathan Thomas: It’s snowing — and there’s a parade outside.

Judith Bernstein: Yes, it’s a good omen. We’ve started on the Chinese New Year!

Thomas: Okay, this sounds a bit crazy.

Bernstein: I see, there’s a disclaimer already. What’s going on here?

Thomas: I was going to say that for its first 268 years, Yale University only accepted students if they were men.

Bernstein: That’s correct.

Thomas: So when you were there as a graduate student from 1964 to 1967, women were not permitted to attend as undergraduates, only men. That changed in 1969, but I’m wondering what it was like for you as a student and as a woman to be in an educational environment that was so imbalanced in this way?

Bernstein: I come from a very modest, middle-class background. When I was at Penn State as an undergraduate, they had three men to every woman. When I went to Yale it was an all-male undergraduate school, but the graduate program admitted a small percentage of women. I was very much aware of the fact that there were only three women in my class and that the rest were men. The instructors were all men, except for Helen Frankenthaler, who was a visiting instructor and only taught a single course. At the orientation address, Jack Tworkov, who was Chair of the School of Art, said We cannot place women. What he meant to say was, If you’re a woman, you’re on your own after you graduate. We can’t help you get a job in an academic setting. That was day one, but it just went in one ear and out the other. Times have changed. Now there are more women at Yale than men.

Thomas: And the cost of getting an MFA has changed too. Today we have the student debt crisis.

Bernstein: It’s true. I got a full scholarship, but if I tell you the amount of money it cost per term you’d think I went during the Civil War!

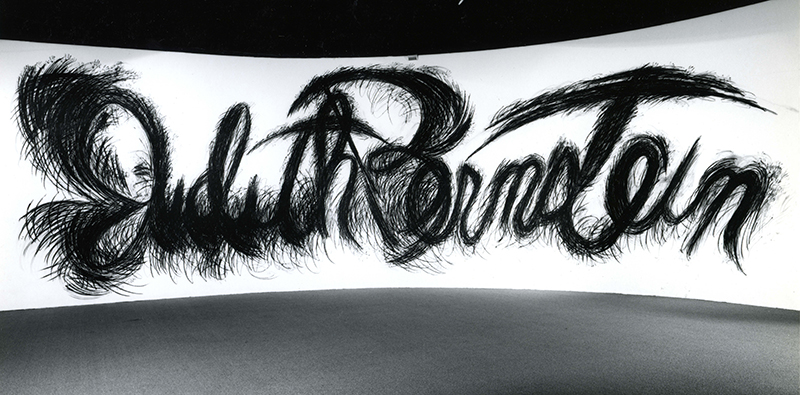

Thomas: That’s funny. Since we’re on the topic of Yale, is that where you first encountered graffiti?

Bernstein: Oh yes! As a grad student I had read an article in The New York Times that said that the title of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Edward Albee’s play, was taken directly from bathroom graffiti. A light bulb went off. I ran into the men’s bathroom to take a look around and said, This is great! My guy friends were the lookouts, so it was fun for me to get an entrée into the men’s room. I got into scatological graffiti, limericks and all the wonderful things behind closed doors. At the same time I had a roommate who was in the theater department and she had a lot of friends who subsequently became my friends. John Guare, a playwright, and Rob Leibman, an actor, would come to my studio and educate me on lots of sexual vocabulary. For me it had a lot of humor, but at the time I didn’t realize that graffiti was actually more profound than that. People are defecating and letting their minds go. There’s no editing. It is anonymous.

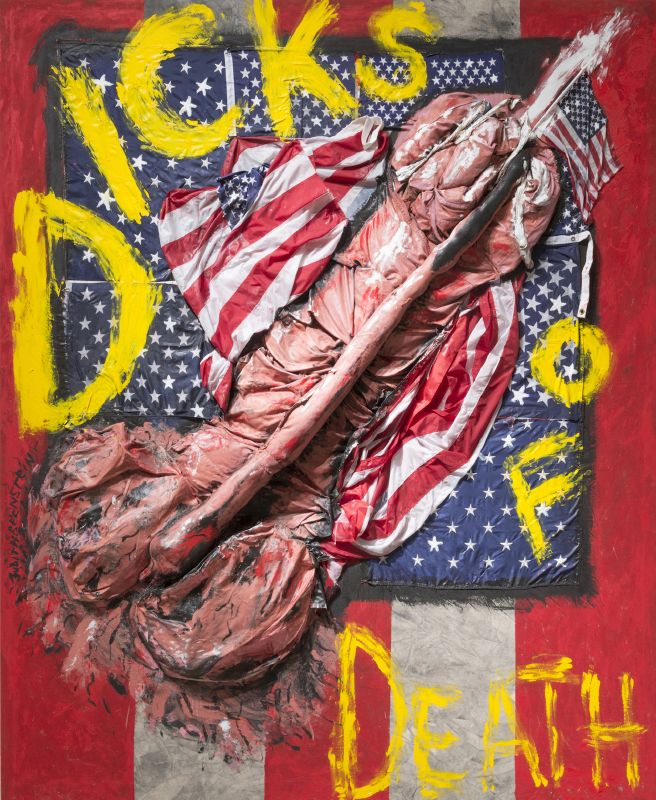

Around the same time, I started making the Dickhead drawings you may have seen in Dicks of Death at Mary Boone in Chelsea. I’ve revisited this material in some of the new paintings, but in the ’60s I used Governor George Wallace, a very reactionary governor from Alabama, as the metaphor for a dick, because he was a real dick! I liked the idea of making his face a cock. In essence it was Feminism. When I was doing all this at Yale, I got some kudos from faculty, but they were mostly hesitant about where I was going with it and what it was about. It was just a lot of fun sticking it to everyone with the mine’s bigger than yours mentality. Then I tied it to the Vietnam War, because there was an enormous amount of fear about going to war and not coming back. The Vietnam War was raging. It was a war that had a draft, and a lot of men escaped it by becoming graduate students at Yale and other schools.

Thomas: I’d like to talk about the war, or how you responded to it at the time with your artwork, but I was wondering if you had any important artist mentors in those years?

Bernstein: I don’t think I really had any mentors when I was younger. Later on I did. I did a commission for a collector named Bill Copley. He ran this publication called The Letter Edged in Black [S.M.S., 1968]. He was also an artist and went by the acronym CPLY. He had the most extraordinary Surrealist collection in the world. It went on auction in 1979 and sold for what was then the largest amount of money for a private collection. And yet it was so little in comparison to what art goes for now. He owned Man Ray’s Lips [The Lovers, 1936]; he owned This is Not a Pipe [Magritte’s La trahison des images, 1928-29], which he sold to LACMA separately before the auction. He had Magritte’s A Big Apple in a Room [La Chambre d’Écoute, 1952], which he sold to Apple Records. But this auction went for $6.7 million, which is nothing in comparison to what things are selling for today. The market just went directly up, like the World Trade Center.

Thomas: You mention Bill Copley because he was a mentor?

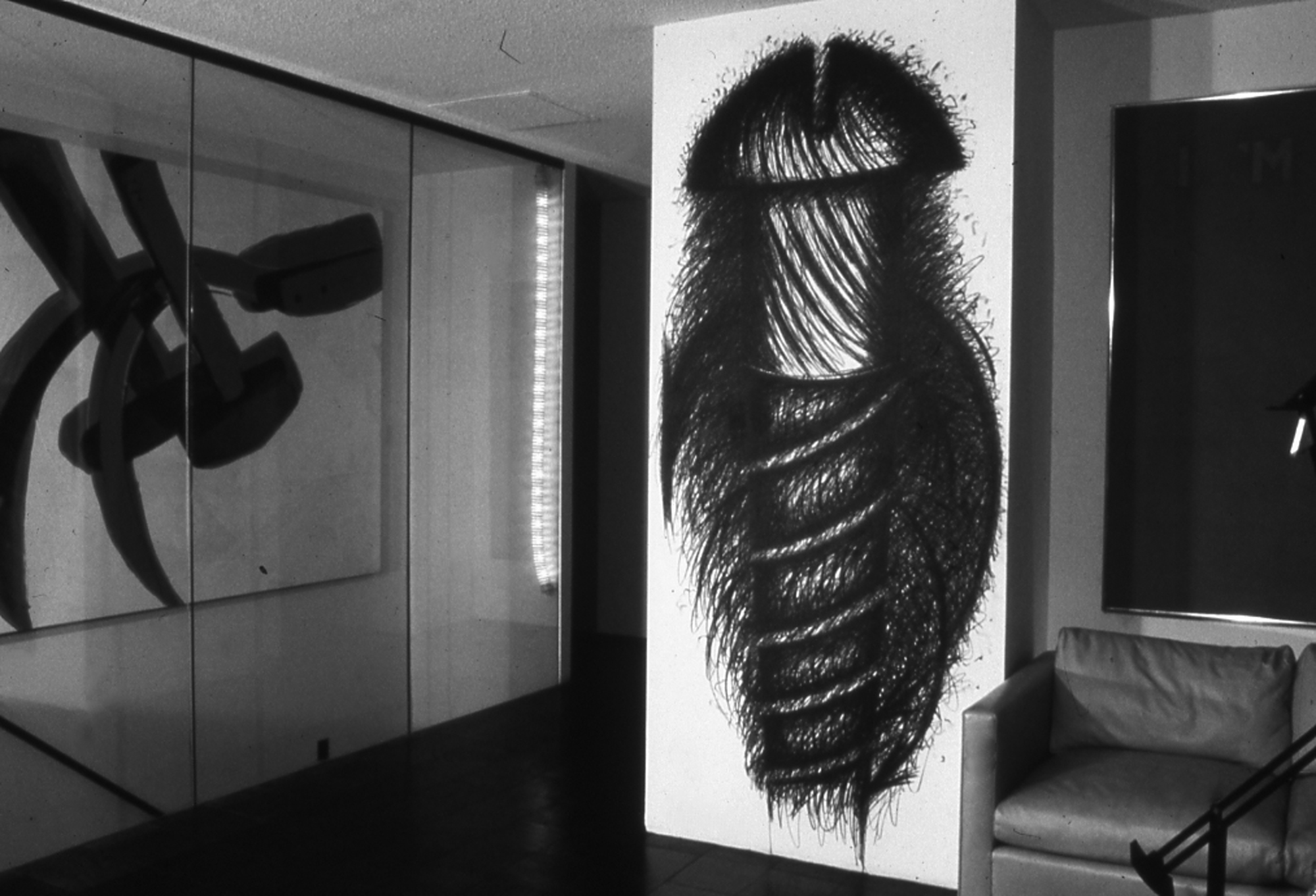

Bernstein: The reason I bring him up is because he commissioned me to do a drawing in his bedroom and a drawing in the living room. He had a townhouse that was near the Guggenheim Museum.

Thomas: What year was this?

Bernstein: It was 1977. I did a giant drawing of a cock right by his bed and Bill was thrilled. I had gone to the University of Colorado to do a lecture, a visiting gig — you know, you have to make money some way — and I said to Bill that one of the people in the audience had asked me if I was trying to make the cock more efficient. And Bill said: If you can do that, you should quit art! You’ll make a fortune! But that was not to be. So I did a giant cock drawing right by Bill’s bed. It was an 1841 European hand-carved bed and the posts looked just like screws, so my drawing mirrored the bed, and was also next to a Duchamp window sculpture. I also did one in his living room and it was right by an Andy Warhol hammer and sickle piece. Then I had my show at Iolas Gallery. Brooks Jackson Iolas was the dealer. It’s not in existence anymore, but Alexander Iolas had a large collection of Surrealist art.

Thomas: Was that in New York?

Bernstein: It was in New York, on 57th Street. Alexander Iolas was the backer and Brooks Jackson was the dealer. Bill would have these wild ART parties where everyone would play chess with huge decanters that were filled with red wine and white wine. Bill had THE collection. He owned Magritte’s picture of a head, a breast, a crotch — there were five canvases — he owned that piece [L’Évidence éternelle, 1930]. Bill was very interesting. He was adopted by one of the last of the robber barons of Chicago.He also went to Yale.

Thomas: Did you meet him at Yale?

Bernstein: No, he was much older than me, by twenty-one years or so. It was 1968 and I was going around to galleries and showing slides of my work (of course there were still slides at that point). I actually first went to Iolas Gallery and they referred me to Bill Copley. They said Bill was an artist making this publication, The Letter Edged in Black, and he would really love my work. That’s how we met.

Thomas: What sort of publication was The Letter Edged in Black?

Bernstein: It was actually quite fabulous. Bill would have a group of artists make a piece, whatever they wanted to do, and he would print it up. Each artist would receive $100. I remember Roy Lichtenstein made one of those hats you would make out of a newspaper as a little kid. So I went to see Bill and he loved the work. We were going to present a Supercock with a big zipper on it. He had all these zippers printed, but unfortunately the publication went belly-up before they published my piece. Bill was an eccentric guy. After he left Yale he went to Paris and painted with Magritte and bought a lot of work. Soon after he opened a gallery in California. He didn’t sell a damn thing the entire time he had the gallery. Nothing, absolutely nothing! Bill said the pieces sold for as little as $25 — now can you imagine! It shows how different those times were. In spite of inflation, that’s still chump change. Bill was like a mentor in those days.

Thomas: He was a mentor in that he supported you by commissioning work and invited you to parties to introduce you to a community?

Bernstein: That’s right. He also got me a show with Brooks Jackson Iolas, which meant exposure. Sometimes people help you along; they don’t do the whole hog, but they help you how they can. There’s not enough of that. It’s also very unusual for anyone to have a mentor at an older age, but I had one recently, since 2008, with Paul McCarthy. A lot of things snowballed from there; waves were created all over. I’ve had three shows at The Box in LA since that encounter.

Thomas: That’s interesting because your paintings from the late ’60s vibe with Paul McCarthy’s videos and performances from the ’70s. It’s the scatological combined with painting and soft sculpture.

Bernstein: It was a perfect match waiting to happen!

Thomas: Is it true that you had an artwork banned from a student exhibition at Yale?

Bernstein: Yes it’s absolutely true. It wasn’t actually a student exhibition, it was an exhibition that was on the green at Yale. Robert Doty was the curator, visiting from the Whitney Museum, but when the curatorial committee saw my piece they said they could not exhibit “this kind” of work.

Thomas: What was the work?

Bernstein: It was a cock, and it looked like a cock, but it was more of an abstract expressionist cock.

Thomas: Was it a painting?

Bernstein: It was a painting, about 3 x 4 feet, and it was penis pink. What happened is that the committee didn’t call me directly. They called Lester Johnson, who was the head of the Yale school at that time, and he called me up and said, This is not appropriate for this show. But let me tell you, all work is appropriate for every show. There’s never a good reason for censorship. His excuse was: Well, you know, this a small venue, this isn’t New York.

Thomas: Had you had any encounters with censorship prior to this?

Bernstein: I had a funny thing happen in 1966. I had sent slides of some of my new graffiti-esque works to get duplicated at Kodak. Kodak wrote me back a letter and said, We don’t duplicate this kind of work. That was censorship, but it didn’t feel like a biggie at the time.

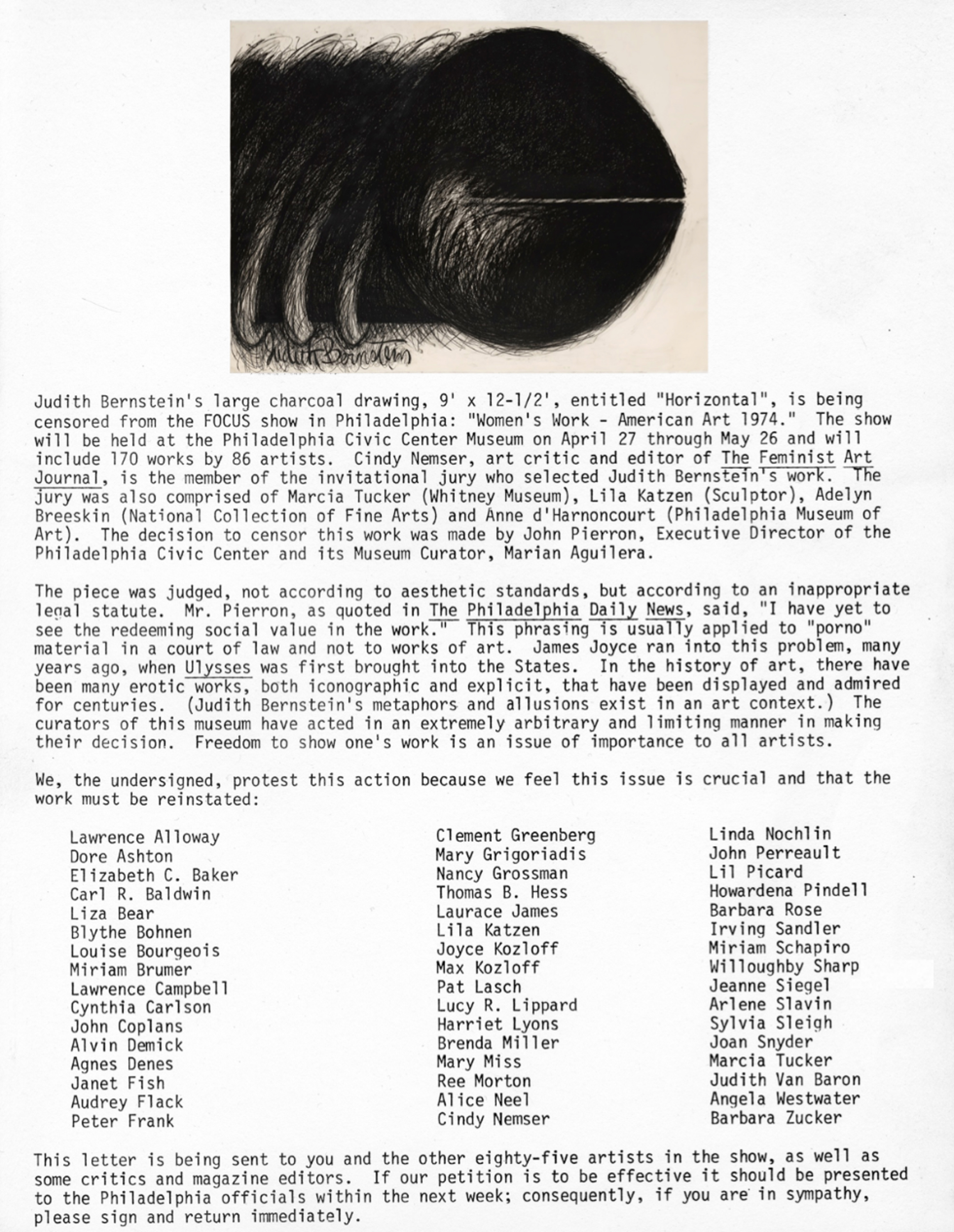

Thomas: You had another artwork censored in 1974. This one’s been written about but I’d be curious to hear what happened. To my understanding you made a charcoal drawing of a screw that was twelve feet long called Horizontal (1973). I read that before it was banned it had been selected by a jury of five women, including curator Marcia Tucker from the Whitney Museum, for an exhibition called Women’s Work — America ’74.

Bernstein: I prefer to call it Focus, because “women’s work” is patronizing. I don’t remember any shows called Men’s Work. But anyway, I sent in a photograph of the piece and everyone got hot and bothered over it. They said, Oh no, we can’t have this in the show! Women will be damaged forever if they see this piece!, which is so ridiculous it’s beyond comprehension. They always want to protect women and children, but nevertheless there’s no protection necessary with this piece. This is one of my absolute favorite drawings ever, Horizontal, 9 x 12 feet. Now it’s my most well-known work.

Thomas: There was also a petition against the censorship of Horizontal that was signed by people like Lawrence Alloway, Clement Greenberg, Lucy Lippard, Linda Nochlin, Willoughby Sharp…

Bernstein: We had a list of extremely prominent people and they were against censorship, and rightly so, because there’s never a reason for censorship. The piece was not reinstated in the show, but they printed up buttons in place of my work that said: Where’s Bernstein? The funny thing about it was that people kept saying, You should go to the show! And my friend, Walter De Maria, said You can’t go to that show! They’re gonna ask Where’s Bernstein? and people will say: She’s right over there! So I didn’t go to the opening. A lot of the publications wanted me to describe the piece, and of course they wanted something very salacious. How round would you say the front was? Would you say it was flat? Was it very round? How dark was it? They wanted a juicy quote. But I said, I’ll send you a photo. In the early seventies you had to have it wired. Oh it was a primitive time.

Thomas: I was also curious about the group you started in 1973, the year before the incident in Philadelphia, called Fight Censorship. I read a statement that described the group as “a collective of women artists who have done, will do, or do some form of sexually-explicit art.” So often historically, this sort of art was made by men with male audiences in mind, but your group stood up against this tradition.

Bernstein: We did the best we could! And it was a hard road because there was so much to contend with. The Fight Censorship group included Hannah Wilke, Louise Bourgeois, Joan Semmel, Anita Steckel, and me. Anita had been a croupier in Las Vegas. She would always say, If a penis is wholesome enough to go into a woman, it should be wholesome enough to go into a museum! She would repeat that line as a mantra wherever she went. And everyone would say, Oh my God, here it comes again. But nevertheless it was very funny, and on target, too.

Thomas: What did you do as a group?

Bernstein: We wanted coverage for our work. Once we had a panel at the New School and Louise Bourgeois was holding her little Fillette (1968), which is a huge rubbery looking cock. She’d hold it like a baby; it was very funny. This was in 1973. We were very adventuresome and we were funny. We wanted to see what we could get from the male-dominated art world. We all had work that had sexual content in it. We all had different aesthetics, but we dealt with sexuality.

Thomas: Your work is also funny. Is it true that you were interested in doing stand-up comedy?

Bernstein: I thought about doing stand-up because I’m naturally funny. Mo Rocca, the comedian, has come to my studio a couple times for improv videos about me and my cats Poohie and PiPi. We did a Cat Lady of the Month video and a follow-up video called Cats on Drugs. We just fooled around. It took me a while to realize how funny a lot of my artwork was. I had these one-liners and catchy phrases that I would use. But I didn’t really think about it because for a long period of time I did those large screw drawings. The screw is funny, but the style and content alludes to war and aggression.

Thomas: I see, because of the implicit violence. But comedy is also aggressive.

Bernstein: It is very aggressive and dark it can be many things. There’s a lot of subtext, a lot of double-entendres. I have a lot of rich material I could use. Maybe I’ll do it as a performance piece? I’m not dead yet!

Thomas: I imagine it’s partly the aggression of comedy that made it difficult for women to have equal access as solo performers. Breakthrough figures of your mother’s generation like Phyllis Diller are embraced as self-deprecating housewives, which is a far cry from the Angry Cunts you’re painting now. I wonder if there’s a connection we can make between stand-up and your paintings and drawings?

Bernstein: I had a lot of funny lines that I put into the Fuck Vietnam works, and that cut back the viciousness. For instance one painting I made with a woman spreading her crotch said “Baby the fuckin’ you get ain’t worth the fuckin’ you take.” It was my version of a soldier’s Christmas in Vietnam, with steel wool and Christmas lights that surrounded the vagina. And I had a piece in a group show at ICA London called Keep Your Timber Limber. They ended up calling the show Keep Your Timber Limber—

Thomas: Great title.

Bernstein: It was a great title. They never had any problem with it. It was the same sort of thing when I had a connect-the-dot drawing called Fucked by Number. It was 16 x 35 feet: size matters! I had made a similar drawing for Vietnam, but later, at ICA, it was for Iraq and Afghanistan. In the end, the penis literally was a gun with a cock, a trigger, and an American flag at the tip. That’s the sight gag. Many clowns used to use sight gags like this. Ironically, I don’t like slapstick that much.

Thomas: That’s interesting. I guess the other connection with stand-up that I see in your work has to do with the way that you collect language. Comedians collect language too. They listen and take notes and file their notes and they have all these scraps of language that they draw from in their routines. Your paintings and drawings are often covered with little fragments of language, usually funny lines, or stark and jarring statements; sometimes this language appears large and bold, like you would see on a sign for a protest march, and sometimes the writing is smaller and scrawled like the bathroom graffiti we were talking about earlier. So it’s often slang, but sometimes you present clippings from articles, too. So I guess I’m curious about this approach to collecting and displaying varieties of the English language in a way that seems, I don’t know, almost ethnographic in scope?

Bernstein: I think putting that ethnographic spin to it is actually very accurate. When I was younger, if someone had a funny jab they would send it to me or I would write it down. So a friend would write There once was a man from… on an envelope and mail it to me. Some I knew, some I didn’t. If I liked it, I’d take it.

Thomas: They brought phrases and sayings to you because they knew already that you were interested in collecting these things?

Bernstein: They always got a kick out of my using what they sent. People would say the damndest things to me, as if I were a psychiatrist. They would tell me about their lovers and the fine points of their sexual activity. It was funny because I didn’t care, but because my work was right out there, they felt that they had permission. So in some ways it was amusing to me, as if I were Dr. Ruth.

Thomas: That’s funny. I also wanted to ask you about your interest in using American flags. We see other flags also, like the COME TO IRAQ travel poster you made in 1968, but the American flag is a constant in your Vietnam series and it also appears in paintings you made last year, like Dicks of Death and Star Spangled Boner. I read that you participated in The People’s Flag Show at the Judson Memorial Church in 1970. That exhibition was organized in response to the arrest of an art dealer who was charged with defacing the American flag because he presented an exhibition of anti-war sculptures that used American flags. So he was arrested, and then three of the organizers of your show at Judson—Faith Ringgold, Jon Hendricks, and Jean Toche—were also arrested and charged with DESECRATION OF THE FLAG. Flags are often conflated with cocks in your paintings from that period, or they grow out of cocks like appendages. It’s just crazy that people around you were actually being arrested for the way they were using flags in an artistic context.

Bernstein: I never put myself in the category of the I-could-be-arrested. Bring it on! The Right wing is always there to defend the American flag. Somehow it’s sacrosanct; it cannot be touched, lit up and burned. I thought of using the flag because of the fact that the people who were pro-war were using it, wrapping themselves in the American flag, in the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. All that Americana was put to use, and the flag was the symbol. When soldiers died, they had the flag-draped coffins. Flags are quite extraordinary, the red, white and blue, it’s not the primary colors but it’s damned close. It’s a very strong image, and when you see it you know it stands for America, the US of A. The flag was perfect for expressing an anti-war position. Now you can dissent and still be patriotic. Currently the Republicans are so far on the right. The Democrats are finally moving more to the left, so that’s great. But they’re still not progressive enough for me! I think that Sanders made Hillary move more to the left. I’m very much for Bernie, and I don’t think I’m going to wind up in hell because I’m not voting for Hillary. Ms. Magazine, Gloria Steinem, said the reason women are for Sanders is because that’s where the boys are. PATHETIC! It’s a projection of herself, but that is sad. And Madeline Albright went and said, There’s a special place in hell for women who don’t support other women. Both of those statements were so so stupid. Albright had used that saying for twenty-five years, but it was simply not appropriate in this context. In the past, she’s gotten a lot of kudos, but that was not the case here, and rightly so. Hillary comes with an enormous amount of baggage. And some of us are sick of the Clinton soap opera. I did vote for Bill twice, and I will vote Blue no matter who. I will definitely support Hillary over Trump in a heartbeat!

Thomas: To go back to Judson, I wonder what you showed in the exhibition? Can you set that up?

Bernstein: I think I’ve always created work in a certain bubble. I would have loved to have shown more back in the day, but I didn’t get the opportunity. I did exhibit at The People’s Flag Show in 1970 at Judson Church, which was by the way always a bastion of the left. I made a piece that contained two US flags, and the bottom flag was all blacked-out and said 20,000 Americans were killed so far in Vietnam. It was a somber one. At the time I had a little Fiat and it had a little ski rack where I put this giant painting and rode it over. I also showed Union Jack-off (1967), an American flag drawing that had two crossed cocks replacing the stars. I thought I would have a lot of problems showing the work, but I didn’t expect that I would be arrested or jailed or anything else, despite the milieu of the time. I put my art above my safety. When I made Fun-Gun painting (1967) I took a hammer and hammered .45 caliber bullets flat on one side to glue onto the canvas. Even now, my priority is my artwork, whatever the consequences.

Thomas: You were also a member of various groups over the years, like Art Workers Coalition, Fight Censorship, the cooperative A.I.R. Gallery, and the Guerilla Girls. What was it like working in these groups — as groups?

Bernstein: They gave me the illusion that I was somehow connected to the art world. I was always an outsider looking in; I was never really in until recently, and that’s why this has been such an extraordinary thing, to be able to get embraced at a much older age. I was also always part of academia, but always as an adjunct, never a full-timer. I enjoyed working with groups because there was a family involved, a chosen, like-minded family. I have to say that one of the funniest groups I worked with was the Fight Censorship group including Louise Bourgeois, Hannah Wilke, Joan Semmel, and Anita Steckel. We fought the common causes, and as a group we did get rewarded for it with shows that revolved around the issues. Artists are not just image-makers, but it goes deeper, because we’re people who think and we’re political.

Thomas: Earlier you said that you were marginalized for many years, that you were only recently taken in and that you now have an insider position.

Bernstein: I have to tell you, it still shocks me!

Thomas: So on the one hand there’s the movement from outside to inside, and on the other hand there’s the progression of aging, of becoming an older woman in the process. Are there challenges or biases you still have to confront as an artist today?

Bernstein: I was part of an article in The New York Times called “Works in Progress,” written by Phoebe Hoban, on the topic of aging. When I was originally called about it, I was 72 (I’m now 73). The author initially said that I was too young, and I said, 72 is too young!? They had Carmen Herrera, who is 100, so I seemed young. You don’t know how much time you have, and recently I had some serious medical issues and didn’t expect to survive. Makes you realize how short life is. I’m very fortunate that my work is being shown all over the world. So it’s a wonderful time for me. I would have loved to have more success when I was younger. I would have had a different life. And you also have to realize that not everyone gets a seat at the table. Sometimes the work can be wonderful and not be acknowledged. And sometimes work that is not acknowledged is as good as what is at the table. Now an awful lot of younger artists get recognition at a much younger age. That makes the rewards so much better. They are smarter about how to represent themselves, show and sell. It’s a wonderful thing. When I was younger, that was not expected. I don’t know what the hell was expected, really. You kind of just did it and thought you’d teach to support yourself. I consider myself very fortunate. I think it’s wonderful to be able to do the work you want to do and survive off of it; it’s such a privilege. And also, to be able to live in New York is a privilege. It’s a cliché, but it’s a goddamned privilege.